DELAWARE SPORTS IN THE 1890S

Late in 1889 an Every Evening reporter observed that, “athletics has taken a wonderful, and it is to be hoped, permanent hold on this community.” Indeed it had. And the sport that had the strongest hold on Delawareans in the Gay Nineties was football. Prior to football, baseball in Delaware had been played well into November; now the baseball playing season wound down in mid-September so area elevens could commence practice.

Football, first played in 1869, was slow to gain a foothold in the First State. Delaware College had received challenges to the gridiron as early as 1883 but didn’t play their first scrimmage until 1889. The Delaware Field Club played the earliest football and dominated state teams for several years. Primitive football produced either total mismatches with lopsided shutouts or, if the teams were evenly skilled, low-scoring exchanges of territory. There was no such thing as the 35-31 shootout popular today. Of Delaware College’s first 75 games there were only four in which both teams scored in double figures.

In Newark when news leaked out in 1889 that the college boys were going to play football Sheriff Bill Simmons swore up and down Main Street that the first corpse carried off the field would mean the end of the game. Sheriff Simmons was on the sidelines but there were no incidents and by the early 1890s Delaware College was the state championship football club.

In 1891 the Newark school completed a shutout sweep of the three Delaware teams: YMCA, 58-0; Warren Club, 30-0; Delaware Field Club, 6-0. It was common practice in those days for schools to welcome any nearby resident to the team, regardless of whether he happened to be a student or not. In 1894 Delaware College announced that future football squads would comprise only matriculated students and the school would no longer engage non-academic institutions in battle. The banner of football supremacy for the rest of the decade passed to the Warren Club.

If football was king of Delaware sports in the 1890s, it reigned over the most diverse kingdom yet seen in the state. Basketball made its first appearance in the Wilmington YMCA in 1894 and the YMCA also began playing the first lacrosse in the state. Over at the Delaware Field Club golf was being played for the first time and was soon seen on the expansive private residences of several Delawareans.

Cricket was as popular as baseball for several years and the Delaware Field Club enjoyed its best year ever at the wicket in 1891, going 5-3-2 against the strong Pennsylvania clubs. New smokeless powder and clay pigeons sparked a revival in shooting - in 1892 there were 60,000 gun clubs across the country. Several marksmen from the Wilmington Rod & Gun Club gained national recognition during the decade.

Croquet was as popular as ever and bowling was coming into its own, the state record game being raised to 256. It was a Golden Age for Delaware boxing with regular weekly exhibitions being fought. Even pigeon racing enjoyed a flurry of popularity. Homing pigeons were shipped 500 miles by rail and released for the race home to the loft. Wilmington birds typically made fine showings in these events. In 1899, 11 of 123 Wilmington birds returned from South Carolina in a single day; only 19 of 720 Philadelphia birds accomplished the same feat.

Baseball, amateur style, could still lay claim as the national pastime in the smaller communities but in Wilmington, as usual, interest ran hot and cold. In 1896 there was just enough enthusiasm to carry Wilmington through its first minor league season from first pitch to final out - but not enough support for a second season in 1897.

On the race track Delaware produced its first superhorse - Saladin, a record-breaking brown colt. For two years Delaware even sported the world’s fastest race track, Dr. James McCoy’s innovative kite track near Kirkwood. Moving almost as fast in the early 1890s were Delaware’s wheelmen, who became recognized as some of the finest cyclists in America.

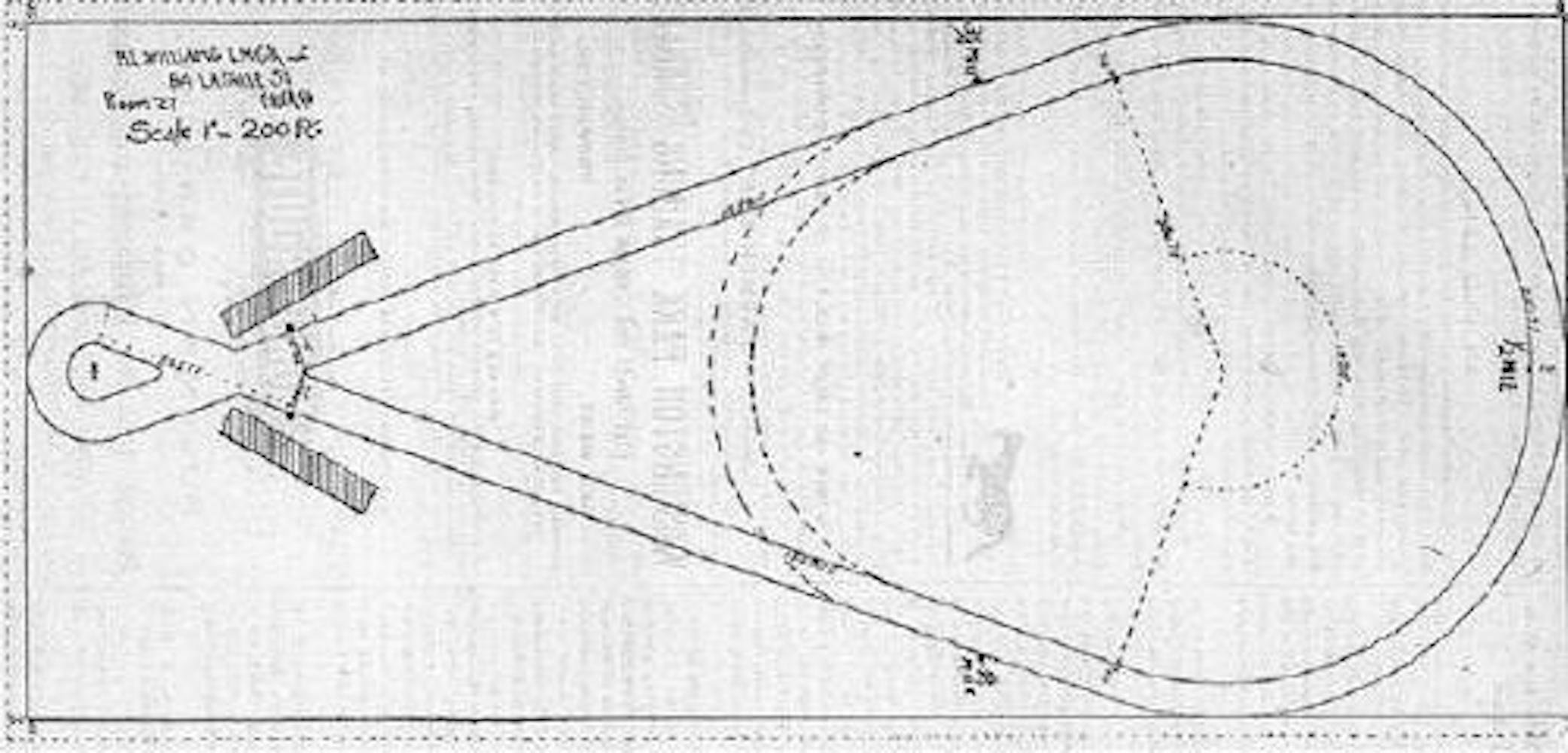

Dr. James McCoy's innovate kite track in Kirkwood made Delaware the speed capital of American horse racing.

But as the decade ended Delaware’s sporting grounds were not nearly as fertile as the rest of the Gay Nineties. There was no pro baseball and the semi-pro Brownson club was so reticent about committing money to the sport they did not even don uniforms. The Warren Club had suffered severe economic reversals, lost their gymnasium which was the finest in the state, and were disappearing altogether. A game of basketball was still not much to look at and bicycle racing was gone. Delaware sports slipped quietly into a new century.

FIRST STATE SPORTS HERO OF THE DECADE: SALADIN

On his farm in Kirkwood about ten miles south of Wilmington medical entrepreneur and sportsman James McCoy constructed a so-called “kite” track that was pinched at one end - a configuration that produced some of the fastest harness racing in the country.

McCoy offered big purses to attract the nation’s finest equine talent. Many of America’s top horsemen sent their top pacers to the McCoy Farm. For Independence Day 1893 he put together his greatest day of racing when he lured Mascot, the world record pacer with a 2:04 mark, to Kirkwood with an offer of $5000 for a new record.

On the track at Kirkwood racetrack operated by the Maple Valley Trotting Association.

Mascot would face the Delaware champion, Saladin, who had set a world record of his own with a 2:09 mark on a half-mile track. In the hyperbolic journalistic style of the day it was said that, “if the race had taken place in New York or Philadelphia it would attract a million spectators.”

Saladin, foaled in California in 1886, was very sickly at his yearling sale in New York and owner James Green was able to claim him for only $500. Many observers doubted the brown colt would even survive the train ride from New York to Wilmington. He debuted in Philadelphia as a 4-year old, finishing second in a 2:30 pace. By 1893, as a 7- year old, Saladin had performed in several big meets around the country and claimed 8 wins in 27 starts.

Some 7000 fans paid 50 cents each to see the two great horses battle. Saladin, with Green handling the reins, broke twice in the early going and trailed Mascot by two lengths at the half-mile pole when he found his stride. Saladin caught Mascot at the 3/4 pole and raced to the wire five lengths the best. His time was recorded at 2:05 and 3/4 seconds.

Fans raced to surround and pet Saladin while others lifted Green to their shoulders and carried him around the track as they yelled themselves hoarse. His feats at Kirkwood thrust Saladin into the class of world-class pacers but he was so fast he soon had no owners willing to test their stock against him and his racing career faded to a close.

OFF-TRACK BETTING COMES TO DELAWARE

Without any advance notice a new establishment opened at 612 Market Street in Wilmington in the winter of 1895. Despite the lack of publicity the Electric News and Money Transfer Company was doing a thriving business within days. It was Delaware’s first off-track betting parlor.

Large blackboards lined the walls of the spacious room listing all sorts of sporting information, mostly for horse racing. Typically ten races, five from New Orleans and five from Arlington, Maryland, were available to Delaware sportsmen. Given the communications of the day, the handicapping information on the horses in the races must have been virtually nil, making the wagering little more than betting on numbers.

Clerks behind frosted windows collected bets and telegraphed the money to the main office in New Jersey where it was played on any race selected. Bulletins provided updates during the races and any winning monies was telegraphed back to the parlor. The Electric News and Money Transfer Company took a 25-cent commission on each play; the minimum bet was $1.00.

Business was brisk with crowds of 150-200 hovering around the parlor during business hours from 2:00 p.m. to 5:00 p.m. Well-known businessmen mingled with the assorted shady characters expected around the fringes of gambling. The operation was perfectly legal but alarmed politicians rushed laws through the legislature banning the gambling parlor. Delaware has not seen legal betting on horse races away from the racetrack since.

DELAWARE GETS A NATIONAL CHAMPION

General Manager Thomas Kane of Wilmington’s Institute Hall had taken special pains to present his building for the occasion. The platform was placed as close to the center of the main floor as possible and raised some four feet. Chairs were meticulously arranged at suitable intervals on all four sides to afford the most convenient and comfortable viewing of the evening’s proceedings. Yes, even the Opera House could not stage a better event, thought Kane.

There was no way Mr. Kane could anticipate the pandemonium that would soon convert his orderly hall into chaos even a New Castle County conventioneer wouldn’t recognize. The Warren Athletic Club’s wrestling program on May 12, 1892 was particularly strong, with the main attraction featuring the American champion, Weiss, of Brooklyn.

Wilmington's Opera House was once a sports mecca.

After several preliminary boxing and wrestling bouts Warren Club member John Cooper appeared to face Weiss. For a full five minutes the 700 partisan fans roared and pounded on chairs in anticipation of the 125-pound match. Officials called for order but could not harness the Warren enthusiasm. Only the referee’s wave to wrestle brought silence in the hall.

Cooper sprang to the offensive throwing his opponent in the opening moments, although the referee failed to award the bout to the Wilmington man. Cooper tackled Weiss again but in the flailing arms and legs the referee was kicked and refused to render judgement on the second fall. The crowd was frothing as Cooper pinned the champion for a third time and was awarded the match. The great victory was achieved in one minute 29 seconds.

Cooper’s hand was not even raised before he was hoisted to the shoulders of Warren men and paraded around the hall. The din of shouts and cries shook the building as the audience rose en masse on top of chairs to salute the new champion. The enthusiasm on the street almost equalled that in the hall. Cooper was shouldered up and down Market Street and feted in celebrations until well past midnight. But Mr. Kane had one more chore. The fallen ex-champ, literally dazed by his beating, had to be carried off the platform and through the crowd to the dressing room by the ubiquitous manager.

Cooper left active competition that year and began an association with the Wilmington YMCA that would stretch into the 1940s. He turned out numerous championship teams and wrestlers, the best being 135-pound Hubert Williams who won the collegiate title with the Naval Academy in 1935. He would one day be the earliest Delaware athlete recognized by the Delaware Sports Hall of Fame.

THE FIRST NIGHT BASEBALL IN DELAWARE

Seeking any way to draw apathetic Wilmington fans to his minor league baseball team manager Denny Long arranged to play the first night baseball game in this part of the country at the Union Street grounds on July 4, 1896. Night baseball was no longer a novelty on the Pacific Coast and a game under the lights in Indianapolis had attracted 10,000 curious onlookers. But Wilmingtonians proved less enthusiastic.

After his regular Atlantic League doubleheader against Paterson Long strung electric arc lights on the ground and up high around the field for a third game. In addition to the ballgame the stands at Union Street afforded an excellent view of the Delaware Field Club’s fireworks down the street.

Wilmington Peaches pitcher Doc Amole was said to have ended Delaware’s first night baseball game by throwing a pitch with a firecracker hidden in the ball.

An oversized, bright white ball was used and the likely apocryphal story has been passed down from that night that Wilmington hurler Morris “Doc” Amole hid a firecracker inside the ball before a pitch to batsman Sam McMackin(some versions of the tale had the immortal Honus Wagner at the plate) in the fourth inning. When McCackin swung and made contact the resulting pyrotechincs caused the bat to shatter and the disgusted umpire ended the game.

If such an incident occurred the Wilmington reporters somehow missed it and did not include the prank in game accounts. As it was, the players couldn’t manage well and score was not kept as the contest deteriorated into a “funny exhibition.” In the end only 200 people showed up to see an event that was fully 40 years ahead of its time.

LIVE BIRD SHOOTS

With the coming of fancy shooting clubs and better equipment target shooting became a much more humane sport in the 1890s but for some nothing matched the excitement of a live bird shoot. One of the last - and best - of these matches took place in Claymont in 1896. The team of Joseph Cross and George Huber of Wilmington squared off against Robert Miller of Wilmington and Reuben Stout of Magnolia in a 50- bird shoot for $200 a side. The four men were widely regarded as the best marksmen in Delaware.

Several hundred spectators turned out even as rumors spread through the town that Cross, the state champion, was gravely ill and near death on the morning of the match. Cross indeed made it to the shooting grounds and struggled to the shooting line. He managed to record 42 kills in 46 tries before fainting and forfeiting his final four attempts. His partner Huber killed all but one bird but nine of his hits fell out of bounds and he was credited with only 40 kills. Miller and Stout recorded 85 legal hits out of 100 to take the prize 85-82.