1900-1910 COURSES

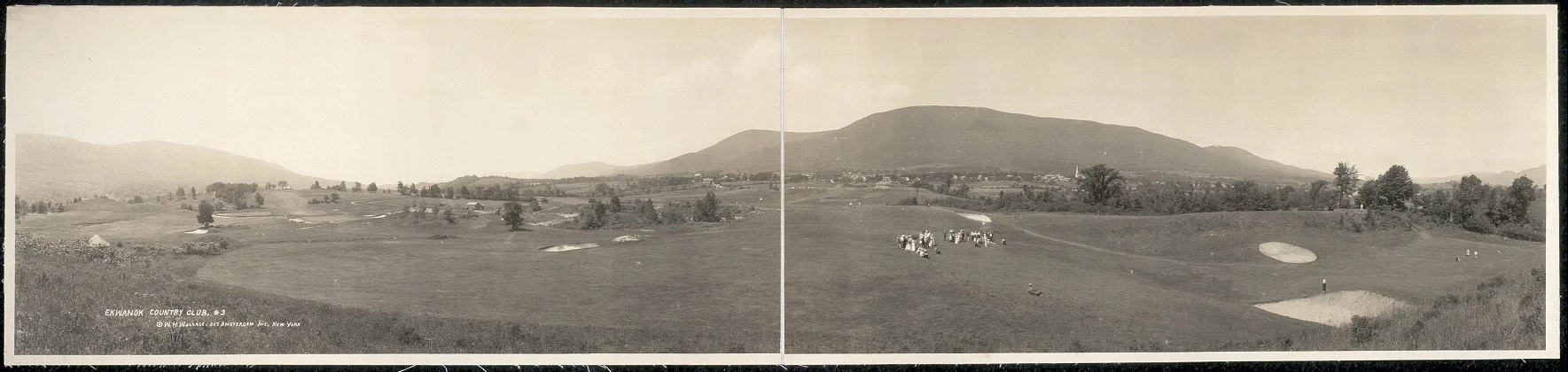

Ekwanok Golf Club (1900)

The most critical element in a championship golf course has always been good turf. And as the game was sending down roots in American soil the best turf was considered to be on Long Island in New York and in the Vermont Hills. Golfers were testing this excellent turf as early as 1881 in the town of Dorset in the Vermont Valley, banging balls into old tomato cans.

In 1886 fifteen men, mostly from nearby Troy, New York, began the Dorset Field Club and played across still-active pastureland, as attested by the longest of the nine holes at 325 yards, Bull Barn. Cows and goats were expected to take care of course maintenance. As the game caught on players needed courses and so-called architects were employed to create golfing grounds. The typical modus operandi was for the architect to spend a few hours walking over open land, pound stakes into the ground to mark where tees and bunkers and greens would go, collect their fee of a few dollars and leave, never to return.

Ekwanok was the first 18-hole American golf course that could stand comparison to the classic British links.

Willie Dunn, an emigrant of Musselburgh, Scotland, was one of these architects who was in most demand in the 1890s. Dunn could not drive stakes into the ground fast enough so he cabled for his nephew John Duncan Dunn to catch the next packet over to America and help him out. While working with his uncle Dunn made the acquaintance of Walter Travis who and only just begun playing golf but was on his way to shortly becoming the best American player in the game.

In 1899 James L.Taylor of Brooklyn bought 200 acres of farmland near Manchester, Vermont and hired his New York friends Travis and Dunn to transform the land into golfing ground. Dunn had the architectural experience but Travis had the doggedness that would make him a great player. Travis made frequent trips to the construction site, fussing over the placement of bunkers and testing shot values. Dunn and Travis gave special attention to green sites, tilting putting surfaces and installing contours that stood in stark contrast to the flat, featureless greens that were the American norm.

When Ekwanok Golf Club opened in 1900 it joined the Myopia Hunt Club as a course that stood to be compared with the British seaside links. And Travis continued to lavish attention on the course, visiting often over the years to make refinements. The course hosted the United States Amateur in 1914 and Francis Ouimet, the hero of the 1913 U.S. Open, won the championship.

After the U.S. Amateur the membership at Ekwanok retreated from the public eye. A special 25th anniversary tournament was held for Ouimet in 1939 and 700 spectators and a national press turned out but otherwise nothing. What can be seen, however, is Hildene, the glorious home of Robert Todd Lincoln, Abraham Lincoln’s son, that is open for tours - he was the Ekwanok president from 1904 until 1926.

Glen Echo Golf Club (1901)

Raise your putter if you know who George Lyon is. Mr. Lyon is the last Olympic gold medal winner in golf, contested in the 1904 games. The venue was the Glen Echo Golf Club. Lyon, a 46-year old Canadian, finished ninth in a 74-man field to qualify for the 32-man match play competition with a two-round total of 169. He upset medalist Stuart Stickney in the Round of 16 and won three more matches against higher-ranked players to capture the gold.

Lyon was actually the only gold medal winner. Golf was an Olympic event in 1900 in the Paris Games but the competition was so haphazard that winners Charles Sands and Margaret Abbott just received flatware. Abbott in fact, whose mother Mary was also in the nine-hole event (the only time a mother and daughter competed in the same Olympic event), thought she was just playing in a regular tournament and went to her grave never knowing she was the first American woman to win an Olympic event.

Representing Canada, George Lyon won the 1904 Olympic gold medal across the Glen Echo fairways.

Only one man played in both Olympic events. His name was Albert Bond Lambert. Albert's father, Jordan Wheat Lambert, had licensed Listerine, now a famous antiseptic mouthwash but in its original incarnation a floor cleaner, in 1881 when he was a local pharmacist. Albert took over the Lambert Pharmacal Company in 1896 when he was just 20 years old but apparently had enough time to indulge his interest in golf.

Lambert sailed to France in 1900, planning to mix business and pleasure. Along with his sample case of Listerine he also packed his golf clubs. In the "Golf Exhibition at the World's Fair Lambert, a rare early left-handed golfer, fired rounds of 94 and 95 at the Compiègne Club that was laid out in the middle of a horse racing track. His total of 189 was good enough to finish 8th in the individual competition and claim top honors in his handicap division.

Back in St. Louis, Lambert's father-in-law, Colonel George McGrew, had been infected by the golf bug after visiting St. Andrews, Scotland and playing rounds with Old Tom Morris. Mcgrew purchased 167 acres of rolling farmland northwest of the city and hired James Foulis of the Chicago Golf Club to design his new Mound City Club course. Foulis was a native of St. Andrews and his father had been the foreman in Old Tom's golf shop. Foulis finished third in the first United States Open and won the second tournament at Shinnecock Hills in 1896.

Mound City, quickly renamed Glen Echo, was the first golf course west of the Mississippi River to be designed as a true 18-hole layout. While jim Foulis was hired for the job, his brother Robert, also a refugee from Old Tom Morris's golfing empire, did much of the heavy lifting in the routing of the course.

James Foulis arrived at Glen Echo after winning the second United States Open in 1896.

The new course was ready for play on May 25, 1901 and McGrew was already hatching plans for a grand world championship with Lambert on board. As McGrew and Lambert worked on their anticipated International Golf Matches the International Olympic Committee was moving the upcoming 1904 games from Chicago down the Mississippi River to coincide with the St. Louis World's Fair. McGrew quickly scuttled his International Golf event and in short order Glen Echo was an Olympic venue.

Lyon was the unexpected champion an on his march to the gold medal set a new Glen Echo course record with a 77. Lambert made it to the quarterfinals of match play before being eliminated. The Olympics were hardly an international celebration of golf in 1904 - 77 golfers entered - 74 from the United States and three from Canada. The team competition featured ten-man regional teams from around the country; as a member of the runner-up Trans-Mississippi Golf Association squad Lamber earned a silver medal.

Golf was scheduled to be an event in the 1908 London Olympics but after a conflict with the Royal & Ancient it never happened and golf disappeared from the Olympics until Rio de Janeiro in 2016. Albert Lambert would be heard from again, though. He led a consortium of businessmen who backed Charles Lindbergh's solo flight across the Atlantic Ocean in 1927, hence the name of his bi-plane, The Spirit of St. Louis. Lambert's name graces the St. Louis international airport - he earned the city's first pilot's license and donated an airfield to encourage early aviation.

Glen Echo wold continue to pop up on the nation's golf radar as well. The course hosted many important state and regional championships, including the 1940 Trans-Mississippi Ladies Championship when two future Hall-of-Famers, Betty Jameson and Patty Berg battled across the historic fairways. Jameson won. The LPGA showed up in 1954 and another Hall-of-Famer, Betsy Rawls, won with the help of a course record 67 against a par of 76. All-time great Mickey Wright took one of her 82 career victories from Glen Echo in 1964 and Shirley Englehorn won the St. Louis Invitational with an even par 216 in 1970, the first of four tournaments she would win in a month culminating in the LPGA Championship.

Glen Echo even got involved in kickstarting another Olympic movement, hosting the first National Senior Olympics in 1987. Architect Pet Dye was in the field and was not shy with his evaluation of the course: "I wouldn't change a thing, even if I wanted to, they wouldn't let me build a course like this today. It's a classic."

Oakmont Country Club (1903)

"There's only one course in the country where you could step out right now — right now — and play the U.S. Open, and that's Oakmont,” Lee Trevino once said. The golf world certainly agrees - more national championships have been staged at Oakmont than any other venue; the 2016 U.S. Open marks the ninth time the USGA has brought its marquee event to the Western Pennsylvania links. Oakmont was the first golf course designated a National Historic Landmark. Somewhere Henry Fownes is smiling.

Henry Clay Fownes was born on September 12, 1856 to Charles Fownes and Sarah Anne Clark, who had emigrated to Pittsburg from England in the early 1840s. The Fownes were iron people and Henry was thrust into the family business at the age of 15 when his father died unexpectedly. In 1881 Henry and his brother William purchased the Carrie Furnace in Rankin on the banks of the Monongahela River which would become the foundation of the Fownes Bros. fortune. Their businesses included Standard Seamless Tube, Midland Steel, Reliance Coke and Shamrock Oil and Gas, in Texas.

Henry Fownes was on a career trajectory that promised to land him among Andrew Carengie, Henry Frick, Andrew Mellon and the other titans of Pittsburgh industry. But his world changed in an instant on an afternoon in 1898 when he was attempting to repair a bicycle tire with a welding torch, a task he had no doubt performed hundreds of times. This day, however, he neglected to use his welder’s mask and his eyes were damaged by a flare-up. When Fownes checked in with his doctor about dark spots in his vision he was informed that he was, in fact, suffering from arteriosclerosis and had only a couple of years left to live.

Fownes divested his interests in the Carrie Furnace to Carnegie and United States Steel and began traveling the country as he shifted his final gears downward into relaxation mode. He began playing golf, quickly becoming one of the better players in the Pittsburgh area and qualified for the national amateur championship in 1901. Meanwhile, he received a new prognosis from his doctors - the eye damage was not the result of lethally hardening arteries, it was merely macular damage from the intense flash of the torch. It was too late to fetch back the Carrie Furnace, which The Iron and Machinery World magazine estimated should have brought $1,000,000 more than it did, but no too late to devote his remaining years to golf.

Fownes put together an investor group called the Oakmont Land Co. in May of 1903 and in July he had settled on 191 acres of the White Oak Level farm which had the advantage of being fairly level and treeless. Fownes feverishly shifted into overdrive. He hired 150 men from the local steel mills and sent them out with 25 teams of horses to shape the land. He paced the property tirelessly, sketching out holes. Twelve were completed before the winter freeze and the remainder of the course was ready for play by the summer of 1904.

While other rich men were constructing playgrounds for their society friends, Fownes had something altogether different in mind for Oakmont. There were no frills, no gala social events. Just golf. And Henry Fownes wanted Oakmont to be the supreme test of golf, ushering in the “penal school” of American golf architecture, where “a shot poorly played should be a shot irrevocably lost.”

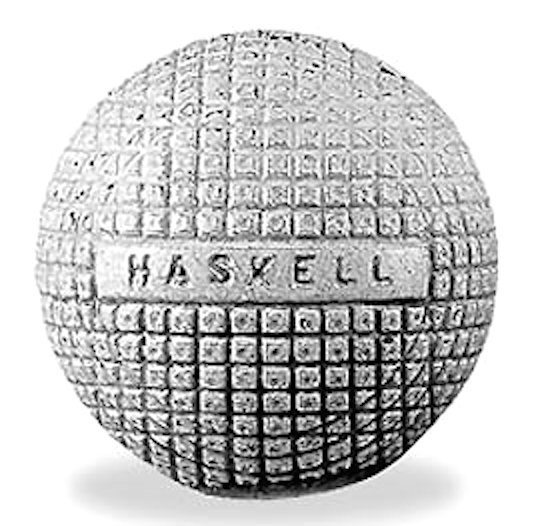

Early Oakmont golfers played a course with a par of 80, including eight par fives and the 560-yard tenth that carried a par six. At 6,400 yards the course was 20 percent longer than most courses of the day. But Fownes was not looking to terrorize golfers with length, he was creating the first golf course for the new Haskell ball. Golfers in the 1500s batted around balls of wood until someone discovered a more forgiving spheroid could be fashioned from boiled goose feathers stuffed into a cowhide. “Featheries” ruled the game until Revered Adam Peterson produced a golf ball using rubber sap from tropical Gutta Percha trees in the mid-1800s.

On April 11, 1889 Massachusetts-born Coburn Haskell and his partner Bertram G. Work, an employee of Akron-based B.F. Goodrich Company, received a patent for a revolutionary golf ball that consisted of rubber threads wound around a solid rubber core. They found that this ball reliably flew 20 yards further than the gutties then in use. Haskell established the Haskell Golf Ball Company in 1901 which brought thousands of new players to the game. The basic golf ball construction devised by Haskell and Work would not be improved upon until 1972 when Spalding introduced the first two-piece golf ball, the Executive. The Haskell ball was what Henry Fownes was looking at when he was tramping across Oakmont, laying out golf holes.

Henry Fownes anticipated the coming of the rubber-cored golf ball by making Oakmont longer than the typical early 1900s golf course.

Henry Fownes, despite coming to golf late in life, went on to qualify for four more U.S. Amateur Championships. His son William, a Massachusetts Institute of Technology-trained engineer, was an even better golfer who qualified for 19 U.S. Amateurs and won America’s most coveted title in 1910 at The Country Club. He would captain the first United States Walker Cup team in 1922 and served as the president of the United States Golf Association for two years in the 1920s. William Fownes was appointed to the club’s board of Governors in 1907 and it was the son - undoubtedly with the father’s counsel and final approval - who was most responsible for turning Oakmont into the course that induced, as Tommy Armour said in 1927, “muscle-tightening terror.”

It was Fownes the Younger, working concert with his greenskeepers John McGlynn and then Emil Loeffler, that created the standard for firm and fast golf in the United States. The greens were raised and slanted, contoured and slickened to an extent never experienced. “I put a dime down to mark my ball and the slid away,” Sam Snead once said.

And then there were the famous Oakmont bunkers. Henry Fownes had designed the original course with about 100. That number would surpass 300 over the years. As technology improved William Fownes would make sure obsolete bunkers were replaced with adequate hazards. Bunkers were brought up to the edges of fairways and greens to challenge better golfers. All were filled with thick, coarse Allegheny River sand that required phenomenal strength to extricate a wayward shot. The most famous set of sand bunkers at Oakmont are between the 3rd and 4th fairways, laid out in advancing rows like church pews. Over the years many a congregant took the Lord's name in vain as he advanced feebly from one sand pit to the next. For a while William employed special rakes that created furrows in the sand intended to remove any element of fate in an Oakmont bunker. Every golfer received the identical lie - bad.

Oakmont and its furrowed bunkers received its first test from the world’s finest golfers in the 1919 United States Amateur. In the tournament 21-year old Oakmont member S. Davidson “Dave” Herron beat 17-year old Bobby Jones 5 & 4 in the finals, in one of the few times the golfing immortal would hear his misses openly cheered in the gallery. But the big winner was the golf course, where few of the competitors approached the par of 73. For one of the first times the efforts of the greenskeepers were recognized as the USGA wrote Loeffler a letter stating, “Never in the history of golf in this country has the championship been played on a course in such fine shape.”

Henry and William Fownes were not quite so jolly after Oakmont hosted the PGA Championship in 1922. Twenty-year old recently crowned United States Open champion Gene Sarazen led a par-busting barrage by the professionals who arrived in western Pennsylvania in the middle of a month’s long drought. Oakmont’s hard fairways caused the course to play short and Sarazen record-setting front nine 32 in his semi-final match was only one example of the low scoring on his way to the title. It would not be the last time Oakmont would prove vulnerable under the right conditions as Johnny Miller proved with his epochal 8-under par 63 to win the 1973 U.S. Open.

Gene Sarazen set scoring records at Oakmont in the 1922 PGA Championship.

Oakmont was back to its fearsome self in time for the 1927 U.S. Open as the winning score of 301, 13 over par, was the highest in modern Open history. Tommy Armour finally won the championship by shooting a 76 in a playoff to defeat Harry Cooper’s 79. The U.S. Open would return to Oakmont in 1935 where a club professional from Pittsburgh named Sam Parks, Jr. became the most obscure winner in the modern age. Attending the event was Edward Stimpson, a captain of the Harvard golf team and Massachusetts state amateur champion.

After watching in amazement as a Sarazen putt rolled off a green and into a bunker Stimpson returned home and invented a device to measure the speed of greens. It consisted of a block of wood three fee long and a concave ramp notched to hold a golf ball. When the ball was released on a flat surface the length of the roll provided a numerical reading that equated to “speed.” Stimpson sent 25 prototypes to the USGA which ignored the device for four decades.

It was the 1970s before the powers that be began concerning themselves with uniform green speed. Stimpson’s design was resurrected, given a few tweaks and reborn as “The Stimpmeter.” To decide on a preferred green speed for its championships the USGA spent two years traveling to courses and testing green speeds. The average was 6.5 and only two were measured at 8.0. When they showed up at Oakmont the reading was 11.5. If the course runs dries the Oakmont greens can read 14 or 15. For the United States Open the club has to slow down its greens to accommodate the best players in the world. And that is only for the twelve flatter greens - six of Oakmont’s putting surfaces are not flat enough to register a Stimpmeter reading. The ball, like Sarazen’s 1935 putt, just keeps rolling and rolling.

Golf engineers tried many experiments to measure green speed before settling on the simple Stimpmeter.

The 1935 U.S. Open would be the last Henry Fownes would see at Oakmont; he died several months later. Charles Fownes took over for his father but his tenure was not a happy one. America was changing and an old-styled British-flavored golf club held little appeal to many members. Charles resisted the membership votes to add the requisite swimming pool and family amenities of a modern country club until he could fight no longer. He resigned in 1946, four years before his death.

Jack Nicklaus won his first professional major at Oakmont in 1962 in an eighteen-hole playoff with local hero Arnold Palmer, accomplishing what his idol Jones had not been able to do 43 years earlier in the face of hometown favoritism. But the golf course was becoming unrecognizable. With the departure of the Fownes family an aggressive tree-planting campaign had gotten underway at Oakmont. No longer could one sit on the clubhouse porch, as Grantland Rice wrote in 1939, and “enjoy the view of seventeen of Oakmont’s eighteen flags.”

The United States Golf Association kept returning but in the mid-1990s, with Oakmont approaching its centennial, the greens committee did an about face and decided to pull every last tree - more than 5,000 - out of play. The course was returned to its beginnings as a British-style links with the winds whipping across the barren landscape. Henry Fownes’ original avenues are still in play, save for the eighth green that had to be relocated about ten yards when America’s first super-highway, the Pennsylvania Turnpike, unceremoniously cut through the course in the 1940s. Yes, somewhere Henry Fownes is smiling.

Pinehurst No. 2 (1907)

A Toast to North Carolina

Here’s to the land of the long leaf pine,

The summer land where the sun doth shine,

Where the weak grow strong

and the strong grow great,

Here’s the “Down Home,” the Old North State

At one time the southeastern United States was covered in more than 90 million acres of Longleaf pine, about the size of Montana. the straight-growing majestic trees made fine lumber and even better turpentine and pitch which was used to waterproof ships. By the end of the 19th century, after two centuries of enthusiastic harvesting fewer than four percent of those forests remained.

And so it was possible for James Tufts to purchase 5,000 acres of denuded wasteland in the North Carolina Sandhills in 1895 from Luis A. Page for $5,000. When he decided he needed more the price for the next 800 or so acres the price had soared to $1.25 an acre. Tufts planned to use the land to construct a “health resort for people of modest means” in the style of a New England village. The locals called Tufts a fool but if this was folly at least he could afford it.

James Walker Tufts was the son of a Massachusetts blacksmith, born on February 11, 1835. At the age of 16 he was sent to apprentice with the Samuel Kidder Company, an apothecary in Charlestown. An inveterate tinkerer, Tufts spent much of his time experimenting with medicinal cures and flavoring extracts. About that time Americans were getting there first taste of carbonated water and sodas with exotic flavors like celery and crabapple and pistachio were all the rage.

After six years Tufts struck out on his own and opened a drug store in Somerville, Massachusetts. He would soon build his venture into one of the nation’s earliest retail chains by adding additional stores around Boston. In 1863 Tufts invented and patented the Arctic Soda Fountain to dispense the flavored seltzer water. Crafted from splendid Italian marble with silver plating and elaborate spigots, these ornate machines were often endowed with classical sculptures.

Tufts won the concession to provide soda water at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia and he created a grand thirty-three foot tall marble fountain to dispense refreshments to the ten million fair-goers as they rode the world’s first monorail and listened to Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone for the first time. Tufts business exploded and in 1891 when several leading seltzer suppliers consolidated to form the American Soda Fountain Company he was made the first president.

About that time Tufts’ Bostonian acquaintances were beginning more and more to escape New England winters by heading to the American South and he heard about the Pine Barrens of North Carolina for the first time. Once he latched onto the idea for a mid-south resort Tufts wasted no time. Within six months the Holly Inn was completed and signing in twenty guests for New Year’s Eve. By the end of 1896 he had added a general store, 20 cottages and a dairy farm.

To create his village Tufts called on the firm of Frederick Law Olmsted, the Father of American Landscaping. Some 200,000 plants, including 47,000 for France, were fitted into the site plan. The village was originally called “Tuftstown” but was soon going by the iconic name - Pinehurst. Tufts selected the name not as a legacy to the North Carolina Longleaf pines but from a list of rejected names for Martha’s Vineyard.

Outdoor recreation was front and center for the Pinehurst health resort from the start. Guests could ride horses, hunt, play polo, bicycle, shoot archery and play bowls on the green. There were two tennis courts. But golf was not considered. James tufts got his first whiff of golf in 1897 when an employee reported that some guests were banging balls around the pasture and scaring the cows. More as a way to protect his milk supply than appease guests with a place to play this game of “pasture pool,” Tufts asked a friend D. LeRoy Culver, who was a New York City public health official, to lay out a primitive nine holes. Culver’s main qualification for the job was that he once visited St. Andrews.

Tufts was surprised when the golfing became so popular the crowded course was taking three hours to complete. In 1899 he retained John Dunn Tucker from a family of Scottish professionals who got their start at Musselburgh Links, the world’s oldest course, to be the first professional at Pinehurst. Tucker added nine more holes for what would become known as Pinehurst No. 1. The course was esteemed enough that the world’s greatest golfer, Harry Vardon, chose to play it on his first tour of America in 1900.

Early golf courses were quiltworks of geometric figures. The No. 1 course opened in 1897 with large rectangular sand greens.

After that 1900 golf season Tucker did not return to the North Carolina Sandhills and Tufts came to an oral agreement with another Scotsman working at Oakley Country Club in Watertown, Massachusetts to become the resort professional. Donald Ross began his working life as a carpenter’s apprentice in Dornoch in the north of Scotland. Scots naturally value a well-crafted brassie over a finely turned piece of furniture so young Donald was soon sent to St. Andrews to learn the art of clubmaking under Old Tom Morris. At the urging of a Harvard professor named Robert Wilson who engaged the personable Ross in Morris’ golf shop Ross sailed to America in 1899 at the age of 26 to work at Oakley. He stepped off the train in Pinehurst in December of 1900. His hiring was one of the final acts for James Tuft who died in 1902.

Ross was hired to oversee golf operations, not as a greenskeeper or to design golf courses. In 1901 the first nine holes of Pinehurst No. 2 were constructed but they only totaled 1,275 yards and Ross may not have been involved in their construction at all. His initial focus was on golf. In April of 1901 Ross and Pinehurst staged their first annual golf tournament, the North and South Amateur Championship with George C. Dutton of Boston topping the table of 16 entrants. A North and South championship for women began in 1903 and there would later be similar championships for junior and seniors as well.

Ross was still very much involved with his own game as well. He finished fifth in the U.S. Open at Baltustrol in 1903 and won the first of two Massachusetts Opens in 1905. He won three of the first seven North and South Opens held at Pinehurst for professionals beginning in 1902. His brother Alec won the other four.

But he was also spending more and more time with his mules and drag pans shaping the golfing grounds of the resort. He completed 18 holes for Pinehurst No. 2 and after finishing up No. 3 in 1910 Donald Ross was officially in the golf course design business. He would go on to design an estimated 400 courses from his base at Pinehurst, including No. 4 in 1919. Ross became known for his use of grass-faced bunkers and elevated crown greens but he more likely to fit his designs to a property than impose a rigid golfing philosophy on the terrain. If there was one trademark to a Ross course it was playability with an emphasis on chipping.

A happy accident happened to Ross in 1913 as he was re-routing No. 1. He wound up with an open 14 acres which he converted into a practice area, considered the first driving range in America. Up until that time lessons were always of the “playing” variety which professionals administering tips on the course. So many golfers took to this concept of pounding balls that the Pinehurst practice area became known as “Maniac Hill.” After 1914 Ross never again designed a course without a dedicated practice facility.

Donald Ross was a golfer before he turned into an architect at Pinehurst.

Donald Ross remained at Pinehurst for 48 years, during which time he tested his design theories on Pinehurst No. 2, which came to be considered his masterpiece - never completed in his mind. The course sported sand greens until the 1935 when Ross planted Bermuda grass overseeded with rye. The next year in November Pinehurst hosted its first major championship with Denny Shute capturing the PGA Championship by downing Jimmy Thomson 3 & 2 in the 36-hole final. Shute, who would join the World Golf Hall of Fame in 2008, was so shy on tour that he was called “The Human Icicle” and often send his wife Hettie to accept his trophies at awards ceremonies. He grabbed the Wanamaker Trophy himself in front of the Pinehurst clubhouse, however.

Another pro golfer who was more than happy with first prize money at Pinehurst was Ben Hogan. Hogan was a regular on the tour in the 1930s but winless for seven years as he battled an inconsistent hook. He had managed six runner-up finishes in the previous 14 months but even the supremely confident Hogan was beginning to see his future in a Fort Worth pro shop and not the professional golf tour when he rolled into Pinehurst on bald tires with $30 in his pocket for the 1940 North and South Open, grateful for the free meals and lodging in the Carolina Hotel Richard Tufts provided entrants.

In the opening round Hogan holed out for birdie from a bunker on the eleventh hole to ignite a course-record tying 66. A second round 67 engorged his lead to seven strokes and he cruised home for his first tour victory with a 277 total. Afterwards he told reporters, ““I won one just in time. I had finished second and third so many times I was beginning to think I was an also-ran. I needed that win. They’ve kidded me about practicing so much. I’d go out there before a round and practice, and when I was through I’d practice some more. Well, they can kid me all they want because it finally paid off. I know it’s what finally got me in the groove to win.”

Indeed he had. Hogan won at Greensboro the following week and then in Asheville at the Land of the Sky Open. After that came four U.S. Opens, two Masters, two PGA Championships and one British Open and one of the greatest careers of all time.

In 1970, after 75 years of ruling its fiefdom, the Tufts family sold the village and the golf complex to Malcolm McLean, inventor of the container ship, and his Diamondhead Inc. corporation for $9.2 million. Diamondhead had big plans for Pinehurst. They put on a 144-hole professional event, started the Golf Hall of Fame and added another course, Pinehurst No. 6. But their main business was real estate development and carving up the village grounds for condos and vacation homes.

Corporate ownership did not prove kind to Pinehurst. Conditions at the golf courses deteriorated as did Diamondhead’s balance sheet. By the 1980s a soft real estate market and bad investments had forced the company into bankruptcy. ClubCorp of America stepped in during 1984 to snatch up the golf course, the hotels, the clubhouse, the gun club and the riding stables for $14 million. Pinehurst’s second corporate overlord was in the resort business, however, and founder Robert Dedman, Sr. treated the historic golf mecca like his crown jewel.

Dedman also set Pinehurst No. 2 on its course to host its first United States Open in 1999. First, the PGA Tour returned in the early 1990s and then the USGA staged the U.S. Senior Open at the resort in 1994 with South Africa’s Simon Hobday winning with a ten-under par total of 274. When the U.S. Open arrived it proved to be a tournament or the ages with Payne Stewart winning a duel with Phil Mickelson with a 10-foot par putt on the 72nd hole while Mickelson kept a private plane on the tarmac waiting as his wife Amy was expecting the couple’s first child.

The event was such a success that the USGA brought the Open back in 2005 with Michael Campbell of New Zealand winning in even par 280. And American golf’s ruling body had even bigger plans for Pinehurst No. 2 - hosting both the U.S. Open & U.S. Women's Open Championships in successive weeks in 2014, an honor no course had ever received before. To prepare for that historic twin bill the design firm of Bill Coore & Ben Crenshaw was retained to restore the course to the scruffier, more natural look that Donald Ross had perpetuated for nearly half a century. Ross would probably grumble that he still isn’t finished with the place yet.

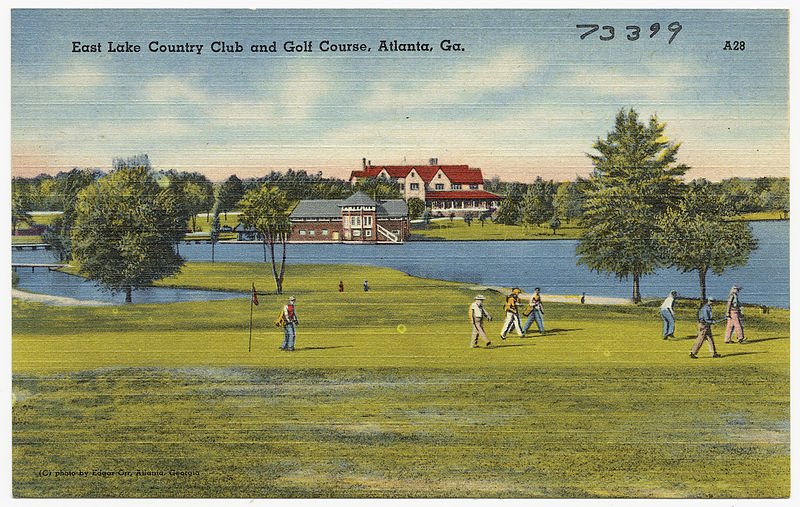

East Lake Golf Club (1908)

Burton Smith, an attorney and brother of Atlanta Journal publisher and future governor and U.S. Senator Hoke Smith, spearheaded the formation of the Atlanta Athletic Club (AAC) in 1898 to foster sports participation in the self-proclaimed capital of the “New South.” The members gathered in a clubhouse in the shadow of the Equitable Building, the city’s first skyscraper, planned and executed by high-rise pioneers Daniel Burnham and John Wellborn Root.

The venture was a success and the club soon boasted more than 700 members. Georgia Tech football coach John Heisman, who would one day have a trophy named for him, was put in charge of the organization’s athletic program. One of his duties was to bring golf to the club and property was acquired in 1904 around East Lake, about seven miles from downtown Atlanta. Tom Bendelow was retained to lay out the new golf course.

The Atlanta Athletic Club helped pioneer golf in Georgia at its East Lake course.

The grand opening at East Lake took place on July 4, 1908 and in attendance was six-year old Robert Trye Jones, named for his paternal grandfather and called “Rob” by his family. His father, Robert Purmedus Jones, had been a promising local athlete before settling into a career as counsel for a nascent soft drink syrup manufacturer named The Coca-Cola Company. Little Rob was an only child, his brother William killed at the age of three months by a gastrointestinal disorder. He suffered from the same affliction and had just started eating solid food a year earlier; his doctor thought golf would be a beneficial activity for the lad.

Before his sixth year was out Bobby Jones would indeed win his first junior tournament at East Lake. But he was not even the most talented young golfer at the club. In 1909 Jones was beaten in a club tournament by 12-year old Alexa Stirling. The trophy, however, was given by scorer Frank Meador to young Rob. “After all,” he concluded, “We couldn’t have a girl beating us.”

Stirling lived in a cottage opposite the club’s 10th tee and played frequently with Jones until her father, an eye specialist, put a stop to it because of Rob’s frequent profanity-laced outbursts on the golf course. Both Alexa and Rob learned the game from Stewart Maiden who came from Carnoustie, Scotland to teach golf. As Jones would write later, “The best luck that I ever had in golf was when Stewart Maiden came from Carnoustie to be pro at the East Lake Club. Stewart had the finest and soundest style I have ever seen. Naturally I did not know this at the time, but I grew up swinging like him.”

In 1913 East Lake members recruited Donald Ross to re-work Bendelow’s quirky layout which included nine holes that concluded across the lake from the clubhouse. Ross’ new routing featured two nines balanced on either side of the lake. Jones broke 80 for the first time at the age of 11 on the new course and two years later he won the club championship.

1916 was a breakthrough year for the young East Lake golfers. Jones qualified for the U.S. Amateur for the first time and the 14-year old made it to the quarterfinals at Merion Golf Club. And Alexa Stirling won the U.S. Women’s Amateur three days before her 19th birthday at Belmont Springs Country Club in Massachusetts, prevailing 2 & 1 over Mildred Caverly in the finals. After the tournament was suspended for two years during World War I Stirling won her second and third consecutive titles.

East Lake teenagers Bobby Jones and Alexa Stirling toured the Untied States and Canada raising money for the Red Cross during the Great War. Here they play Montclair Golf club in Montclair, New Jersey.

During the war Jones and Stirling were part of the “Dixie Kids” who toured North America raising more than $150,000 for the Red Cross playing exhibition matches. Jones continued to display volcanic tirades and would recall that, “I should have known that Alexa, not I, was the main attraction, I behaved very badly when my game went apart. I think the low point in this regard came in a match at Brae Burn in Boston. I heaved numerous clubs, and once threw the ball away. I read pity in Alexa’s soft brown eyes and finally settled down, but not before I had made a complete fool of myself.”

From that time forward Bobby Jones became the model of deportment and gentleman golfer but as he would ruefully admit, “To the finish of my golfing days, I encountered golfing emotions which could not be endured with the club still in my hands.” The tour was also transformational for Alexa Stirling who met her future husband, Dr. W. G. Fraser, in Ottawa where she lived out her life until 1977. She added two national Canadian championships to her golfing resume as an honorary member of the Royal Ottawa Golf Club.

Jones continued as a member of East Lake as he embarked on the greatest amateur career golf has ever known. After he retired he served as club president for awhile, as his father had also done. On August 15, 1948 Bobby Jones played a round at East Lake Golf Club with his friend Charlie Yates which would turn out to be his last. Stricken by syringomyelia, a neurological spinal disease, he was no longer able to complete a golf swing with the pain in his back. He underwent his first spinal surgery shortly afterwards.

The public got its first glimpse at the East Lake No. 1 course when the U.S. Woman’s Amateur became the first USGA event ever held in Atlanta. Beverly Hanson, a bassoon player from North Dakota who would win the inaugural LPGA Championship five years later, won the final 6 & 4. In 1963, with Arnold Palmer serving as the last-ever playing captain, the United States thumped Great Britain 23 to 9 in the Ryder Cup at East Lake.

By this time however the pioneering Atlanta club was facing tumultuous times. In a half century the city had grown out to the one-time “suburban” location and the surrounding neighborhood was considered one of the roughest and crime-infested in the neighborhood. The Atlanta Athletic Club purchased land further away from the city and put the East Lake property up for sale in 1968. Bobby Jones, who always considered himself a member of the AAC and not the course, followed the club out to Duluth north of the city. He would die at the age of 69 three years later.

A group of 25 starry-eyed AAC members ponied up $1.8 million to buy the old course and rechristen it East Lake Country Club. It was not easy. A black tarp was draped over a chain-link fence to hide the course. One day a gun materialized through a gash in the tarp by the third tee and a voice from the other side demanded money. Wallets were slid through the opening. The club was forced to advertise for members as revenue dried up.

In 1993 a savior in the person of Tom Cousins, an Atlanta businessman. He purchased East Lake and kickstarted a renovation of the neighborhood as well. Architect Rees Jones (son of World Golf Hall of Fame architect Robert Trent Jones but no relation to Bobby), known as the “Open Doctor” for his renovation work on historic championship courses, was brought in to give muscle to Donald Ross’ 80-year old design. Since 2004 East Lake Golf Club has been the permanent home for the season-ending Tour Championship for the PGA Tour.

Bobby Jones’ “defection” has been forgiven as well. The entire clubhouse at East Lake, a Tudor confection designed by award-winning architect Philip T. Shutze in 1926, is maintained as a shrine to Atlanta’s favorite golfing native son.

The National Golf Links (1909)

Charles Blair Macdonald coined the term “golf architect” and this is where he proved what it meant. After the “Father of American Golf Architecture” established a beachhead for golf in Chicago with the first golf course built west of the Allegheny Mountains (see Downers Grove Golf Course) he came east to New York City in 1900 to become a partner in one of the future foundation firms of the brokerage giant Smith Barney. From the moment he arrived in the Big Apple Macdonald was determined to build the country’s best course somewhere in the New York metropolitan area.

To prepare for his masterpiece MacDonald traveled to Great Britain to grill the world’s best players on what they thought the best golf holes were. He visited classic links courses and made notes and drawings. When he took possession of 250 acres along the shores of Peconic Bay at the eastern tip of Long Island, Macdonald was ready to get started. To C.B., a great golf course meant linksland - sandy, nearly treeless soil and his new property near Southampton did not disappoint on that score.

Macdonald set about replicating the great holes of the British Isles onto his existing topography. He added his own flair, making some, such as the 197-yard one-shotter 4th hole arguably a better hole than its inspiration, the Redan hole at the North Berwick West Links. There were versions of the Road Hole from St. Andrews and the Alps off of Prestwick Golf Links, the home of the Open Championship. Macdonald also sprinkled in some of his own creations. Whereas American golf courses of the day were often just laid out with little thought by greenskeeper and mysterious character with Scottish names, Macdonald gave thought for the first time to shot values and how holes fit together with one another.

Macdonald also knew theimportance of green sites and created the best set of greens American golf had yet seen, large and rolling putting surfaces that yielded several acceptable pin placements to complement the hole design. Work began on the National Golf Links in 1907 and play was opened in 1909. Macdonald never stopped tinkering with details of the course over the last three decades of his life but he got sufficiently close to satisfaction to declare, “The National has now fulfilled its mission, having caused the reconstruction of all the best known golf courses existing in the first decade of this century in the United States, and, further, has caused the study of golf architecture resulting in the building of numerous meritorious courses of great interest throughout the country.”

No less an authority than the pre-eminent British golf writer, Bernard Darwin, concurred. "If there is one feature of the course that strikes one more than another,” Darwin wrote, “It is the constant strain to which the player is subjected to; he is perpetually on the rack.” Golf architects have checked in on the National Golf Links for instruction and inspiration ever since.

The National was tabbed to host the first ever international golf match between a team representing the Royal & Ancient Club from Great Britain and a team from the United States golf Association. George Herbert Walker, an investment banker and maternal grandfather to one American President and great-grandfather to another, donated the winner’s cup and his name to the event. A powerful eight-man assemblage led by Bobby Jones and Francis Ouimet who both won their singles and doubles matches led the U.S. to an 8-4 victory in the very first Walker Cup. The National Golf Links would host the event again in 2013 (another American victory) but other than that outsiders rarely are afforded a look inside the fabled club gates.

Bobby Jones, here with Calvin Coolidge in 1921, helped the United States team to victory in the first Walker Cup, held at the National Golf Links.

For many visitors the most striking architectural feature of the National Golf Links is the 50-foot high windmill that peaks above the treeless dunesland from various points on the course. A member suggested it might be a nice touch for Macdonald to construct a windmill reminiscent of those New York’s Dutch founders had used on Long Island. The club founder thought that was a splendid idea and camouflaged the course water tower with a handsome shingled windmill - and then sent the bill for its construction to the member who had dared think his club needed improvement.