1911-1920 COURSES

Interlachen (1911)

From the time six members of the Bryn Mawr golf club north of Minneapolis learned their nine holes were destined to become front yards and housing foundations they set their sights on a golf course that could host national tournaments. The first step was new property and they found 146 rolling acres southwest of the city and close to the streetcar line. On the property was one of Minnesota’s 11,842 lakes - Mirror Lake - and so when the club was incorporated on December 31, 1909 it was called Interlachen, a German work roughly translating to “between lakes.”

To build its championship course Interlachen turned to William Watson, a Scottish pro who arrived in the United States in 1898 when he was nearly 40 years and quickly became one of the pioneering golf architects in the Upper Midwest, even having a hand in the Bryn Mawr operation in 1899. Watson gave the new layout a touch of St. Andrews with a massive double green 175 feet long and more than 100 feet wide to serve the ninth and 18th holes.

To design an appropriate accompanying clubhouse the club sent architect Cecil Bayless Chapman on a tour of midwestern golf clubs and he delivered a handsome Tudor Revival creation sited atop the highest hilltop for miles around that was ready for the grand opening on July 29, 1911. Two years later Interlachen was hosting the Minnesota State Amateur Championship and in 1914 the Western Open, one of early professional golf’s majors, was teeing it up in Medina.

Jim Barnes, who would win the first two PGA Champions, won the first of three Western Opens. It was also the tournament where members would be introduced to Willie Kidd who finished second. Kidd would begin a stay of 37 years as Interlachen’s professional in 1920 and would be followed by his son, Bill, for another 36 years.

Jim Barnes was the most successful American pro of the World War I era.

Not satisfied with their early success Interlachen members recruited Donald ross to makeover the golf course in 1919 and his efforts helped push the club onto the national stage with the 1930 U.S. Open. Bobby Jones came into the tournament having already won the British Amateur and the British Open championships. In the sweltering Minnesota heat the Georgian amateur got off to an indifferent start against the professionals as he came to the signature ninth hole, a par five that crosses a large pond, in the second round.

A mishit shot from the fairway landed well short of the water and seemed certain to disappear into the pond but the ball skidded across the surface to the opposite bank where Jones got up and down for birdie. He backed up his good fortune on the “Lily Pad Hole” with a dominating 68 in the third round to score a two-stroke win and leave Interlachen three-quarters of the way to his immortal Grand Slam. Reporters from 226 newspapers around the world had made their way to Edina to cover the event.

During her career Glenna Collett was often called the “female Bobby Jones” or just the “Queen of American Golf.” In 1924 the long-hitting Collett won 59 out of 60 matches, her only loss coming in the semifinal of the 1924 U.S. Women’s Amateur on the first playoff hole when opponent Mary Browne’s ball ricocheted off hers and into the hole. She won five other U.S. Amateurs between 1922 and 1930, however, and tossed in a French Amateur and a couple of Canadian Amateurs as well.

In 1931 Collett married Edwin Vare, had two children and her recreational activities tacked more towards activities like needlepoint. In 1935 she was back on the course seeking a record sixth amateur title at Interlachen. Standing in her way was 17-year old Interlachen member Patty Berg. Just two years earlier young Patty had shot 122 attempting to qualify for the Minneapolis City Championship. She devoted herself to the game, won the city title the following year and now had reached the finals against the finest female player the United States had ever produced.

More than six thousand partisan spectators turned out for the match but the steady Vare was never in trouble before closing out the precocious Berg 3 & 2 on the 34th hole. Berg would get that Amateur championship three years later at Westomreland Country Club in Wilmette, Illinois. She became the first woman to ink an endorsement deal with Wilson Sporting Goods and would go on to become the first president of the LPGA, winning a record 15 majors. When the first Vare Trophy for lowest scoring average on the LPGA Tour was handed out in 1952, Berg was the recipient. Patty Berg and Glenna Collett Vare would be reunited in the World Golf Hall of Fame.

Interlachen was scheduled to host the U.S. Open again in 1942 but World War II intervened. The next time the USGA came calling the club was told the course was now too short for modern professionals. Robert Trent Jones was hired to bulk up the holes but after examining his suggestions the members decided to stick with their traditional Donald Ross set-up. Jones’ Hazeltine would garner future U.S. Open sojourns to Minnesota.

Interlachen was not off the USGA radar however. The U.S. Senior Amateur showed up in 1986 and the course entertained the Walker Cup in 1993. In 2008 Interlachen was awarded the U.S. Women’s Open when Inbee Park became the youngest champion ever at age 19.

Shawnee on the Delaware (1911)

In 2015 A.W. Tillinghast became only the sixth architect inducted into the World Golf Hall of Fame. Shawnee was the first course he designed. The year was 1907 and Tillinghast was 33 years old. There was little evidence that he bore the stamp of greatness.

Albert Warren Tillinghast was born into a Philadelphia family of privilege where his father helmed a rubber company. As a young man in America's Gilded Age he certainly did not squander his opportunities. Tillinghast never bothered to graduate from any of the many schools he attended. He was a fixture at society parties and indulged his many passions in the arts and sports, of which one was golf.

Tillinghast played a good enough game to reach the Round of 32 in a couple of limited field United States Amateur championships in the early 1900s. While not recognized as an outstanding golfer "Tillie" nonetheless seemed to know everyone in the expanding world of golf. The commission for Shawnee came from one of those friends, industrialist Charles Campbell Worthington.

Golf was just one of many interests that a young Albert Warren Tillinghast, pictured here in 1909, explored.

Worthington was a Brooklyn native, the son of Henry Worthington who made a fortune perfecting the delivery of steam heat to New York City. Charles took over the family pump business at the age of 26 after his father died in 1880. He mad scores of technical improvements to pumps and compressors as the business spread worldwide.

The 1880s found Worthington in Great Britain working on the problem of supplying water to British troops across hundreds of miles of North African desert. His solution earned him citation for and honorary knighthood by the crown. Worthington returned to America with more than a KBE suffix to add to his name. He learned golf on the links of Scotland and England.

In 1887 Worthington was a part of the "Apple tree Gang" that formed St. Andrews Golf Club, the first organized golf club in America. Later he laid out six holes to play on his estate at Irvington-on-Hudson. Meanwhile, he sold his business interests in 1900 and retired at the age of 1946 to live the life of a gentleman farmer and sportsman.

Charles Worthington began acquiring land in the Delaware Water Gap in New Jersey and Pennsylvania, including two large islands in the Delaware River, Shawnee and Depue. He started farming on Shawnee and in the surrounding mountains he imported whitetail deer from Virginia to replace deer that had been hunted to extinction in New Jersey.When he tore down the eleven-mile fence protecting the herd, the roaming deer became the ancestors of deer herds across the state.

Worthington's retirement did not last long, however. He became fascinated with the new horseless carriages and was soon in the automobile business with his Worthington Meteor steam cars. And he decided to develop Shawnee Island into a resort. Worthington erected the Buckwood Inn and summoned his friend Tillie to design an 18-hole golf course.

It quickly became apparent that the inexperienced Tillinghast had finally found his calling in life. Previously unfocused, he totally immersed himself in the project, as he would golf architecture for the next three decades. He also became a prolific golf writer and photographer, editing Golf Illustrated magazine. Tillinghast was one of golf's first "list-makers," issuing a ranking of America's top 12 golfers each year.

Shawnee would go on to become an incubator of golfing "firsts." Worthington was concerned with presenting a top-rate resort for his guests and business associates and that meant a properly groomed golf course. At first he imported a genuine Scottish sheepherder with his flock and dogs to do the job. When that proved inadequate Worthington devised a gang mower with three moving wheels that could be pulled by a horse - shod i leather boots to protect the fairways of course.

First winner of the Shawnee Open, Fred McLeod, was the first honorary starters at the Masters tournament in 1963.

In 1919, Worthington invented a tractor to pull the contraption and founded the Shawnee Mower Company, later to become the Worthington Mower Company. Worthington mowers quickly became the standard in golf course maintenance. During World War II Worthington machines were so useful in maintaining military airfields that they were awarded Army-Navy "E" and "Star" awards for their contribution to the war effort.

In an age when amateurs ruled the game, Worthington was an early proponent of professional golf. In 1912 he started the Shawnee Open, one of the nation's earliest professional tournaments. Scottish-born Fred McLeod, who won the United States Open in 1908 and would become an honorary starter at the Masters from 1963 until his death at the age of 94 in 1976, was the first winner. Events like the Shawnee Open helped spur the creation of the PGA of America which formed in 1916 with one-time Shawnee greenskeeper Robert White as its first president.

The Shawnee Open was an annual stop on the PGA Tour until 1937; Walter Hagen won the first official Tour event at Shawnee in 1916 after reaching the island by horse-drawn boat. In 1938 Tillinghast's course hosted the PGA Championship, then contested at match play.Sam Snead, who was representing Shawnee as a touring pro, reached the 36-hole final against Paul Runyan and was a heavy favorite. But the short-hitting Runyan, nicknamed "Little Poison" sprinted to a five-up lead after the morning round and closed out Snead 8 and 7 for the largest margin ever in the finals.

There would be other big tournaments at Shawnee - a University of Colorado defensive back named Hale Irwin would win the NCAA Division I championship in 1967 - but not on the PGA circuit. After 1938 the Shawnee Open would continue under the banner of the Philadelphia Section of the PGA of America. In 1943, a year before his death at the age of 90, Charles Worthington sold Shawnee to band leader Fred Waring, ushering in a new era at the resort.

"Waring's Pennsylvanians" were among the best-selling bands of the Roaring Twenties and Fred went on to become a radio personality known as "the Man Who taught America How to Sing." He also financially backed the world's first electric blender which invaded American kitchens as the ubiquitous Waring Blender.

Fred Waring turned Shawnee into a playground for his celebrity friends. Bob Hope, Lucille Ball, Perry Como and many others were regulars at the resort on the Delaware. Jackie Gleason played his first round of golf at Shawnee and shot 143, a score somewhat inflated by his insistence at trying to play out of a water hazard. Gleason was instantly hooked by the sport, however, and plunged into a regimen of instruction and practice that saw him post a 75 within 18 months. The Great One remained one of golf's biggest celebrities, founding the Jackie Gleason Inverrary Classic on the PGA Tour in 1972 that continues at the Honda Classic.

But Shawnee's most celebrated "golf first" took place during one of Fred Waring's tournament shindigs in 1954. Pennsylvania native Arnold Palmer had long wanted to attend one of Waring's golf bashes but could never afford to take time off from his job selling paint for Bill Wehnes in Cleveland. The chance came in 1954 but it took winning the United States Amateur Championship the week before at Detroit Country Club to earn the 25-year old Palmer an extra week off from work.

Arnold Palmer was reading an uncertain future before coming to Shawnee in 1954.

During the tournament Fred Waring's college-aged daughter Dixie and her friend Winifred Walzer served as unofficial tournament "hostesses." After a practice round Palmer bumped into the girls and casually invited Walzer to come out an watch him play the next day. The 19-year old from nearby Coopersburg was indeed on the Shawnee links the following day, ostensibly to follow her "Uncle Fred." Palmer spotted her on the 11th hole and the pair were inseparable the rest of the week. By Friday Palmer had won the tournament and proposed marriage.He and Winnie, the girl he first saw at Shawnee, would reign as golf's First Couple for 45 years until her death in 1999.

Shawnee remains a golfing haven open to the public, despite periodic flooding of the island in the Delaware River. An additional nine holes have been added to A.W. Tillinghast's original 18, which includes one-shot holes across the river. In 2011 the resort celebrated its centennial and there was plenty to remember.

Merion East Course (1912)

When most early American golf clubs wanted a course they tapped their best players to do design honors. The result was a proliferation of bland layouts dominated by square greens and narrow rectangular cross-bunkers in the fairways. It was different when the Merion Cricket Club on suburban Philadelphia’s Main Line called on Hugh Irvine Wilson, a 31-year old insurance executive, to build a new course on 127 acres of newly purchased land in 1910.

Merion’s existing course had been well-regarded, hosting the United States Women Amateur in 1904 and 1909. But the new long-flying Haskell ball rendered the original layout obsolete. Wilson knew nothing of golf beyond his ability to play it. He would later confess that he would never have attempted such a project had even possessed the tiniest inkling of what was involved. He began by consulting with Charles Blair MacDonald, self-professed holder of all the golfing knowledge in America. His correspondence with government agronomists Dr. Charles V. Piper and Dr. Russell A. Oakley, recommended by MacDonald, wuld run to over 2,000 letters and culminate with the establishment of the USGA Green Section in 1920 with the scientists as co-chairmen.

The Merion Cricket Club before the members discovered golf.

Wilson’s overriding goal was to create a course that was testing to the expert but ultimately playable by the duffer. When the new Merion course opened in September of 1912 it was apparent that he had succeeded admirably. Experts raced, calling it the country’s finest inland course. The club was swamped with new members and Wilson was soon back at work on a second course on rolling woodlands about one mile away. The West Course, considered a sporty, more scenic but less demanding layout, was officially opened in May 1914. The Merion Cricket Club now had a championship-caliber course and a “member’s course.”

Unlike other novice creators Hugh Wilson did not travel to Great Britain to inspect and emulate the great seaside courses before routing Merion East. It was his contention that the course should be observed for a couple of years to determine where hazards and bunkers should be placed. When it opened, Merion East was observed to have fewer bunkers than most nine-hole courses. Wilson made the obligatory trip abroad in the spring of 1912 after the East course had been seeded. Family lore maintains that he had booked return passage on the Titanic but his investigations delayed him.

The time for sand traps arrived in the summer of 1915 as Merion East prepared for the following year’s U.S. Amateur. In went 50 strategically spotted bunkers and all new tees. New greens were rebuilt on several holes. The Philadelphia Inquirer came out to look around in the spring of 1916 and reported, “Nearly every hole on the course has been stiffened so that in another month or two it will resemble a really excellent championship course.”

Twenty-six year old Charles “Chick” Evans of Chicago won the championship to become the first holder of both the U.S. Open and Amateur titles in the same year. Evans, who never used more than seven clubs, was hired by the Brunswick Recording Company to make records with golf tips but when he discovered that the money might jeopardize his amatuer status he created the Evans Scholars Foundation for caddies that has sent over 10,000 bag toters to college with over $300 million inn contributions as the largest scholarship organization in sports.

Chick Evans was the first player to win the United States Open and the United States Amateur championships in the same year.

But the bigger story at Merion Cricket Club that week was the introduction of the only player to ever duplicate Evans’ feat of being the Amatuer ann Open champion, a 14-year old schoolboy named Bobby Jones who was making his first golfing appearance outside of the South. Used to the slower Bermuda greens in his native Atlanta Jones qucikly learned the lessons of “billiard greens” when he tapped a putt off the green and into a creek during a practice round on the West Course. Jones was also possessed of what the newspapers generously termed a “fiery spirit.”

In his opening match with former U.S. Amateur champion Eben Byers the two players sent so many clubs airborne that players behind them commented it looked like “a juggling act on stage.” On the 12th hole Byers heaved a club over a hedge and commanded his caddie to leave it. Jone prevailed 3 and 1 and attributed the win only to the circumstance that Byers had run out of clubs first. Jones lost in the quarterfinals but he was destined to return to Merion.

Hugh Wilson went on to design a handful of other courses for friends in the Philadelphia area, including the city’s first municipal track at Cobbs Creek for players of “slender purses” and finishing George Crump’s final four holes at Pine Valley, but otherwise did not parlay his triumphs at Merion into more notoriety. Such was not the case with Wilson’s collaborator and right hand man, course superintendent William Flynn.

Flynn was born in Milton, Massachusetts in 1890 and grew up playing golf against the likes of Francis Ouimet. When hired by Wilson to spearhead construction of Merion East his resume consisted of a course laid out in Heartwellville, Vermont. Flynn would stick around Merion for more than a quarter-century while branching out into the golf architecture business, spreading what came to be called the “Philadelphia School” of course design with an emphasis on natural topographical construction. Flynn did his most high profile work modernizing Shinnecock Hills and his best original designs among dozens of courses include Cherry Hills Country Club in Denver and Lancaster Country Club in Pennsylvania Dutch Country.

Flynn is also the man responsible for Merion’s signature wicker baskets, red going out and orange coming in, that are used on the greens instead of flags. Although used in Scotland as early as the 1850s there is no consensus on how the one-of-a-kind hard, ovate-shaped baskets came to be used at Merion. They showed up sometime between the opening of the East Course in 1912, when they were not in use, and 1915 when Flynn took out a federal patent on the wicker baskets. The baskets, which afford the golfer no idea about tricks being played by the wind, fit in perfectly with Wilson’s goal to present the player with a problem to be solved on every hole. Merion also has no yardage markers on its courses.

While much esteemed Merion East had some noticeable flaws when it opened. Not the least was the playing across Ardmore Avenue, then a sleepy country road, on four holes. The chance to set things right came in preparation for the 1924 U.S. Amateur. Land was purchased on the south side of now busy Ardmore Avenue, property Wilson had been eying when he laid out the original course but could not use. The new additions were universally applauded and Jones put the stamp of greatness on the course by drubbing George Von Elm 9 and 8 to win his first United States Amateur championship after six tries. Hugh Wilson’s East Course was finally complete and he would succumb to liver failure less than six months later, dying prematurely at the age of 45.

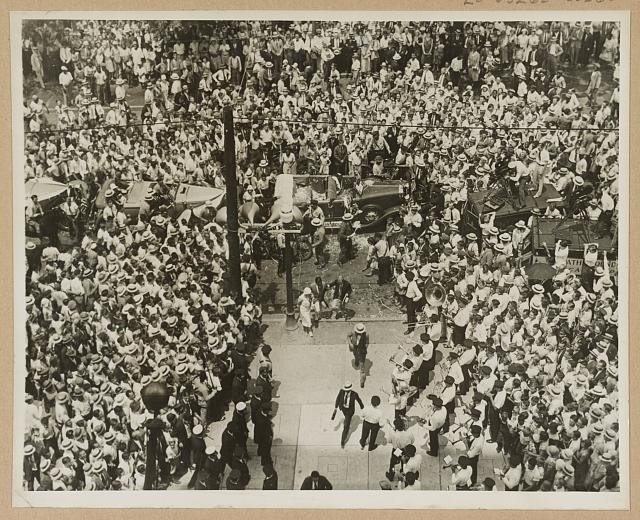

Bobby Jones was not through with his Merion experience. Six years later the U.S. Amateur was back and seeking to win what his friend and biographer O.B. Keeler termed the “impregnable quadrilateral” - winning the Open and Amateur championships of both the United States and Great Britain in a single year. The national amateur title at Merion in September was the last and Jones advanced to the final, settling his nerves each evening with a libation and hot bath. An estimated throng of 18,000 - by far the largest gallery American golf had seen to that time - turned out to see Jones duel Eugene Homans. Jones won 8 and 7 and was led to the clubhouse from the 11th green through his admirers by a platoon of four dozen marines to complete what the New York Times gushed was “the most triumphant journey that any man traveled in sport.”

Jones retired from golf after completing his Grand Slam at Merion. He was 28 years old and had finished first or second in nine of his final ten major tournament appearances. Of the 13 major titles Jones collected since his first, the United States Open at Inwood Country Club in 1923, five were United States Amateur championships. And he never the 12th tee a second time in any of his wins.

Bobby Jones retired from championship golf after winning the 1930 U.S. Amateur at Merion and was embraced by adoring crowds.

The short 378-yard 11th hole was again the scene of high drama when Merion East hosted its first United States Open in 1934. Gene Sarazen was leading by three strokes before hooking his tee ball into Cobbs Creek and leading to a triple bogey seven; the Squire lost the tournament by a single stroke to Olin Dutra. The drama at Merion was ratcheted up even higher in 1950 when the U.S. Open marked the return to action for Ben Hogan whose Cadillac coupe crashed head-on with a Greyhound bus trying to pass a truck on a two-lane Texas highway on February 2, 1949. Only his reaction to throw himself across his wife Valerie’s body in the passenger seat spared his life as the steering column was driven straight through the cushion of the driver’s seat.

El Paso doctors weren’t sure the golf star would survive his injuries which included a mangled left collarbone, a double fraction of his pelvis, a crushed ankle, and an assortment of lacerations and bruises. Golf was out of the question and learning how to walk again was the goal. But sixteen months later Hogan was back in action. He had played a few events leading up to the U.S. Open but none required 36 holes on the final day. Hogan, who played his first U.S. Open at Merion in 1934 at the age of 21, haunted the leaderboard for the first three rounds but never had the lead. He trailed Lloyd Mangrum, the 1946 U.S. Open champion, by two strokes going into the final round but Mangrum bogied six of his first seven holes in the Saturday afternoon finale and Hogan took a two-stroke advantage into the final nine holes.

Coming down the stretch Hogan faltered in gathering heat and needed a par on the long 458-yard 18th to join Mangrum and George Fazio, who had made two late birdies, in the clubhouse at 287, seven over par. After a drive to the center of the fairway Hogan delivered one of golf’s most famous shots, striping a 1-iron to the center of the green and two-putting to gain the playoff. Refreshed the next day, Hogan was the only one of the trio to break par and claim the third of his record-tying four national Opens.

It was playoff time again the next time the U.S. Open arrived in Merion in 1971 in a match-up between golfing royalty in the form of Jack Nicklaus and Lee Trevino, a one-time Texas driving range pro. The Merry Mex broke the tension on the first tee by pulling a rubber snake out of his bag and tossing it to Nicklaus, who asked the see the toy serpent that had been used to demonstrate how deep the rough was earlier in the week. Trevino beat Nicklaus 68 to 71 in the playoff and went on to add the Canadian Open and Open Championship trophies in the next month to become the only player to win all three titles in the same year.

The United States Golf Association has returned to Haverford and the Merion Cricket Club more times than any other venue for its national championships, earning the club a designation as a National Historic Landmark. But after the 1981 U.S. Open won by Lou Graham the East Course, which checked in at 6,544 yards, was considered too short to hold another Open. The USGA finally relented and returned in 2013, stretching the course to within a whisker of 7,000 yards. Worries about an assault from modern professionals proved unfounded as no one broke par, Englishman Justin Rose winning by two with a 281 total.

The century-old Merion East had stood the test of time but creator Hugh Wilson would not necessarily have been pleased. To bolster its defenses the USGA grew penal rough, narrowed fairways and shaved greens. Wilson never understood the constant quest for “billard table” greens and always counseled clubs to let the grass grow and encourage playability by members. As for lengthening his course Wilson was always a proponent of a standardized golf ball, if not adopted by the sport than at least by individual clubs. After all, a golf ball traveling a uniform distance would be lot simpler solution than the time and expense of continually replacing bunkers and tees.

Toronto Golf Club (1912)

The hand of nature more than the hand of man is often given the thickest cut of credit for developing the classic seaside British links course. And so it was not until a Cambridge-educated barrister named Harry Shapland Colt cast aside a law career to that England got a golf course designer who had not been a golf professional.

Colt laid out the Rye Course on the southeast coast of England in 1894 to begin his transformation into golf. He was nominated as a Founding Member of the Royal & Ancient Rules of Golf Committee in 1897 and his connections there helped him win out over 400 plus applicants when the job of Secretary at new Sunningdale Golf Club came open in 1901.

Colt burnished his reputation at Sunningdale with the changes he initiated on the course. He became an acknowledged master of creating inland courses with his ability create a seaside-naturalness to Heathlands landforms. H.S. Colt was the first architect to plot out tree-planting schemes for golf courses and was a pioneer in integrating golf courses into residential communities.

Colt and his design partners Charles Hugh Alison, John Morrison and, for a short time, Alister MacKenzie would ultimately be responsible for over 300 golf course around the globe, becoming the first international golf architecture firm. Colt was 41 years old when he made his first journey to North America in 1911 to design the Toronto Golf Club.

In tow, Colt brought with his design philosophy which would guide so many architects in the years to come, including Canada’s master designer, Stanley Thompson: “It may be well to bear in mind that golf is primarily a pastime and not a penance, and that the player should have the chance of extracting from the game the maximum amount of pleasure with the minimum amount of discomfort, as punishment for his evil ways. He will not obtain this pleasure unless you provide plenty of difficulties, but surely there is no need for vindictiveness.”

The first professional British golf architect, Harry Colt, introduced the concept of natural looking bunkers in North America.

James Lamond Smith, a transplant from Aberdeenshire, Scotland and large property owner on the Glen Stewart Ravine, introduced golf to Toronto in 1876. The Toronto Golf Club was the third to form in North America, after the Royal Montreal Golf Club, founded in 1873, and the Royal Quebec Golf Club, founded in 1875. The members first amused themselves in vacant pastures north of the city but were eventually able to cobble together an 18-hole course that was good enough to host the fourth Canadian Amateur Championship in 1898; George Lyon, who would be Olympic gold medalist in 1904, won his first of a record eight national titles.

In 1909 new land was acquired on the banks of the Etobicoke River in Mississauga on the opposite side of town. When Colt arrived he found a favorable golfing ground imbued with bumps and rolls and a plentiful working budget. Before he left he seeded the course with grass imported from Finland. He came back two years later after the course had opened to fine tune his design and Canada had its first championship golf course, the landmark to which all subsequent courses would be compared.

The hand of nature more than the hand of man is often given the thickest cut of credit for developing the classic seaside British links course. And so it was not until a Cambridge-educated barrister named Harry Shapland Colt cast aside a law career to that England got a golf course designer who had not been a golf professional.

Colt laid out the Rye Course on the southeast coast of England in 1894 to begin his transformation into golf. He was nominated as a Founding Member of the Royal & Ancient Rules of Golf Committee in 1897 and his connections there helped him win out over 400 plus applicants when the job of Secretary at new Sunningdale Golf Club came open in 1901.

Colt burnished his reputation at Sunningdale with the changes he initiated on the course. He became an acknowledged master of creating inland courses with his ability create a seaside-naturalness to Heathlands landforms. H.S. Colt was the first architect to plot out tree-planting schemes for golf courses and was a pioneer in integrating golf courses into residential communities.

Colt and his design partners Charles Hugh Alison, John Morrison and, for a short time, Alister MacKenzie would ultimately be responsible for over 300 golf course around the globe, becoming the first international golf architecture firm. Colt was 41 years old when he made his first journey to North America in 1911 to design the Toronto Golf Club.

In tow, Colt brought with his design philosophy which would guide so many architects in the years to come, including Canada’s master designer, Stanley Thompson: “It may be well to bear in mind that golf is primarily a pastime and not a penance, and that the player should have the chance of extracting from the game the maximum amount of pleasure with the minimum amount of discomfort, as punishment for his evil ways. He will not obtain this pleasure unless you provide plenty of difficulties, but surely there is no need for vindictiveness.”

The original clubhouse at the Toronto Golf Club was a deserted mansion known around town as the "haunted house."

James Lamond Smith, a transplant from Aberdeenshire, Scotland and large property owner on the Glen Stewart Ravine, introduced golf to Toronto in 1876. The Toronto Golf Club was the third to form in North America, after the Royal Montreal Golf Club, founded in 1873, and the Royal Quebec Golf Club, founded in 1875. The members first amused themselves in vacant pastures north of the city but were eventually able to cobble together an 18-hole course that was good enough to host the fourth Canadian Amateur Championship in 1898; George Lyon, who would be Olympic gold medalist in 1904, won his first of a record eight national titles.

In 1909 new land was acquired on the banks of the Etobicoke River in Mississauga on the opposite side of town. When Colt arrived he found a favorable golfing ground imbued with bumps and rolls and a plentiful working budget. Before he left he seeded the Toronto Golf Club layout with grass imported from Finland. He came back two years later after the course had opened to fine tune his design and Canada had its first championship golf course, the landmark to which all subsequent courses would be compared.

The Greenbrier - Old White Course (1914)

This is a place where Davy Crockett signed the guest book. Joseph Kennedy honeymooned here and his son was one of 26 American Presidents to visit. It is one of the rare places in America where public golfers can challenge the design genius of Charles Blair Macdonald, the “Father of American Golf Course Architecture.” And yet the most famous bunker on the property isn’t out on the golf course, it is beneath the West Virginia Wing of the hotel, an emergency hideout large enough to house every member of Congress in the event of a nuclear attack. This is The Greenbrier.

The first guests tied their horses in White Sulphur Springs to “take” the restorative waters in 1778 when the valley in the Allegheny Mountains was still part of Virginia and when Virginia was still a part of England was being disputed. By the 1830s the resort consisted of a collection of cottages including the President’s Cottage that had been constructed in 1835 as a private summer residence of Stephen Henderson, a Scotsman who emigrated to Louisiana and raised sugar cane on the grand antebellum Destrehan Plantation. Henderson died in 1838 and Greenbrier’s finest guest cottage was spruced up for Martin Van Buren’s arrival.

The Chesapeake and Ohio Railway arrived in 1873 and purchased the resort in 1910. The first order of business was to build an opulent hotel with a four-story high Neoclassical portico and the second was to get golf going in the mountain retreat. For the latter job the resort turned to Alexander H. Findlay. The son of a British Army officer, Alex was born below deck in a British sailing ship in 1865. Once on land, he received his first three hickory-shafted golf clubs and a supply of gutta percha balls when he was eight years old. Findlay grew up at the Royal Montrose Golf Club, where the Medal course is the fourth oldest in the world.

Young Alex left Scotland for America in 1886 but unlike so many of his countrymen he was coming not to be an evangelist for golf but to be a cowboy. He soon found himself far from the golfing universe in the Sandhills of Nebraska, working on family friend Edward Millar’s Great Plains spread. Findlay claimed Teddy Roosevelt and Buffalo Bill Cody as friends. One day in April of 1887 Findlay began whacking gutties across the dunelands as an amusement and he was soon asked to lay out six holes for play on Millar’s Merchiston Ranch.

After that Findlay’s involvement in the early rush to golf in America disappears but he resurfaces in 1896 in the employ of Henry Flagler. Henry Flagler, a failed salt miner, went into the oil refining business with John D. Rockefeller in 1867 and together they built the biggest business empire in the world. Although Rockefeller’s is the name most associated with Standard Oil, he always gave the credit to its success to Flagler. On a wedding trip to Florida with his second wife in 1881 the Flaglers visited St. Augustine where they were charmed with the town’s Old World Spanish flavor. In short order Flagler gave up day-to-day operations at Standard Oil and set about developing St. Augustine as “the Newport of the South.” His vision would soon extend down the peninsula, however, extending his railroad and development all the way to Key West by 1912. What Flagler started in St. Augustine with a 540-room hotel would grow into a personal bet of $50 million on the future of Florida.

Some of that money went to Findlay to construct Florida’s first golf course at the Palm Beach Golf Club. And then St. Augustine Golf Club and St. Augustine Country Club and Ormond Links Golf Club and Miami Golf Links. By the time the Chesapeake & Ohio came calling to lay out its initial nine holes known as the Lakeside Course in 1910, Findlay was responsible for over 100 golf courses from Basking Ridge Country Club in New Jersey to San Antonio County Club in Texas. With the hotel and golf course completed the resort took the name The Greenbrier for the first time.

In 1913 the Greenbrier decided to add its first full 18-hole course and engaged Macdonald who recreated several famous European holes in the flat valley stretching out before the Old White Hotel that had stood on the grounds since 1858. Sharp-eyed visitors could spot the chasm of Willie Dunn’s original greens in Biarritz, France at the one-shot third, the fortified diagonal green of the 15th hole at North Berwick on #8, the hillocks that hide the fairway on #13 like the #17 Alps at Prestwick and the severely pitching green on #15 that is an ode to the famous Eden, the eleventh hole at St. Andrews.

With a homemade grip Howard Taft hits away from a sand tee - one of 26 U.S. Presidents to visit The Greenbrier.

The Old White Course, which gave the golfing public a chance to experience Macdonald’s work for the first time, was named for the rickety hotel which was razed in 1922. President Woodrow Wilson was on hand to help introduce the Old White when it opened in 1914, one of the more than 1,200 rounds Wilson played in the White House - our most dedicated golfing President. The former head of Princeton University played mostly for his health, however, and rarely broke 100.

In 1921 the PGA tour began stopping at the Old White. Jock Hutchinson, who that year became the first American citizen, albeit naturalized from his native Scotland, to win the Open Championship took top honors in the White Sulphur Springs Open and the next year the flamboyant Walter Hagen wont he title - the same year he became the first American-born player to win the Open Championship. Later in 1922 Glenna Collett won the first of her record six U.S. Women’s Amateur titles over the Old White Course. The tournament remains the only time the USGa has staged a national championship at The Greenbrier.

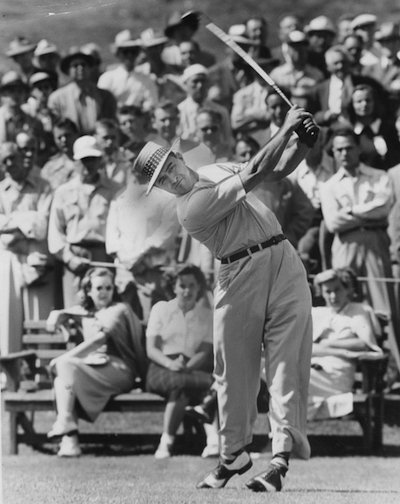

Samuel Jackson Snead was born in Ashwood, Virginia in 1912, thirty-five miles as the crow flies across the Allegheny Mountains from White Sulphur Springs. Considered the greatest natural athlete to ever play the professional tour Snead won his first tournament as a professional in 1936 at The Greenbrier in the West Virginia Closed Pro championship. He opened with a 61 on the Greenbrier course that Macdonald protege Seth Raynor designed in 1924 and closed with a 70 on the Old White to win the two-day event by 16 strokes. It would not be the last time Slamming Sammy would lay waste to Mountain State golfers. He would win the West Virginia Open 17 times, including by eight strokes for the final time when he was 61 years old. He was also the oldest player to ever make the cut in a U.S. Open that year.

The Greenbrier did duty during World War II as a rehabilitation hospital, treating 24,148 patients. In the 1950s the United States government would return with a more covert mission. A massive Emergency Relocation Center was constructed under the hotel with everything the United Congress would need to operate the government should the United States suffer a nuclear attack. The bunker stood ready unknown to the public until the Cold War ended in the 1990s and the Washington Post exposed its existence in 1992. The bunker was decommissioned and opened for tours.

After World War II ended Sam Snead came back to be head professional at The Greenbrier and remained affiliated with the resort until his death in 1992. For many years the annual Spring Festival was the centerpiece event at the resort and none was ever more eventful than 1959 when Snead around The Greenbrier course in a 59 during The Greenbrier Open, a feat that Sports Illustrated would later anoint as “the greatest competitive round of golf in the history of the game.”

As Snead piled up 185 tournament wins worldwide he also scored 42 holes-in-one, using every club in his bag save the putter. One of the aces, all witnessed and attested, came swinging a 3-iron with only his left hand. The last ace came in 1995 when the 83-year old Slammer knocked it in the hole on the 18th hole of the Old White Course for the fifth time.

The ageless swing of Sam Snead produced a 59 at The Greenbrier.

In the 1970s the courses at The Greenbrier began to receive facelifts. Jack Nicklaus remade Raynor’s Greenbrier Course in his own image in 1977 and two years later the reworked course hosted the Ryder Cup. In 1994 it hosted the Solheim Cup and remains the only course to host both the international matches of the men’s and women’s pro tours. In 1999 Robert Cupp finished a complete makeover of Findlay’s original nine holes that were expanded to 18 in 1962 by Dick Wilson, now called the Meadows.

The Old White’s turn came in 2000. But Richmond architect Lester George was not looking to makeover Macdonald’s historic course but to restore it. With the work completed the PGA returned in 2010 with the Greenbrier Classic. Australian Stuart Appleby fired a final-round 59, matching Snead’s historic total to win the event. you can’t make this stuff up.

Scioto County Club (1916)

Scioto is one of a select quartet of courses that has hosted the five greatest American men’s golf competitions: U.S. Open (1926), the Ryder Cup (1931), the PGA Championship (1950), the U.S. Amateur Championship (1968) and the U.S. Senior Open Championship (1986, 2016). And some how Jack Nicklaus, who grew up here, managed to miss them all. Too young, too old, too professional.

Samuel Prescott Bush, the father of a U.S. Senator, the grandfather of a President and the great-grandfather of a President, was among the patriarchy of Scioto Country Club in Upper Arlington, Ohio in 1916. Bush was a Master Mechanic from the Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken, New Jersey when he came to Columbus in the 1880s to work with the railroads. In 1901 he began running the Buckeye Steel Castings Company for the Rockefeller family. The new club was named for the Wyandot Indian word for “deer.”

Gathering at a golf tournament in 1918 at Scioto.

The founders brought in Donald Ross to design the first eighteen-hole golf course in Ohio. The layout quickly earned the reputation as a shotmaker’s course which was validated in 1926 when Bobby Jones won the second of his four U.S. Open titles at Scioto. In the gallery was 11-year old Charlie Nicklaus, who was from a family of boilermakers in Columbus. Young Charlie was helping out around Meb’s Pharmacy and Fred Mebs got him the tickets. Later Mebs sold his clerk his set of clubs. Nicklaus was appreciative of the push towards golf and played in the 70s but he wanted more to emulate Doc Mebs as a pharmacist.

He went to hometown Ohio State University to get a pharmacy degree and then worked for Johnson & Johnson to support his wife, Helen, and a son born in January of 1940 named Jack William. Charlie Nicklaus finally bought his dream pharmacy in 1942 and by 1948 was doing well enough to join Scioto, a few blocks from the Nicklaus house. Two years later he introduced his son to golf and he famously shot 51 in his first round.

The year before Jack Nicklaus started playing golf Scioto got a new professional, 39-year old Jack Grout, an Oklahoman who had played the Tour for awhile but had settled into a career as a club pro after World War II. Charlie enrolled his son in one of Grout’s two-hour group junior golf classes and Jack Nicklaus never had another teacher his entire career. Grout would join the Hall of Fame for club professionals as would two other Scioto pros, George Sargent and Walker Inman.

Jack quickly became a star of the class and Grout favored his star pupil by taking him inside the clubhouse later that summer when Scioto hosted the PGA Championship. Nicklaus got Sam Snead’s autograph and had a memorable encounter with 1946 U.S. open winner Lloyd Mangrum: “He had a scotch sitting on the table, cards in one hand and a cigarette hanging out of his mouth and he said, ‘What do you want, kid?’ I remember it like it was yesterday.”

The Nicklaus trophy case began filling almost immediately: the Scioto Club Juvenile Trophy at 11, the first of five straight Ohio State Junior Championships at 12, a U.S. Amateur appearance at 15, an Ohio State Open at 16, a first U.S. Open and a first national championship in the U.S. National Jaycees Championship at 17, the first of two U.S. Amateur titles at 19. At this time Scioto Country Club had given Nicklaus an honorary membership and after he married Barbara Bash the next year the reception was held in the club. Nicklaus pictured his life as a pharmacist like his dad and a gentleman amateur golfer like his idol Jones. His golfing life turned out a bit different.

Scioto and Nicklaus had a falling out in the 1960s and it came from a misunderstanding over the course. Nicklaus recommended architect Dick Wilson to execute a re-design of the course but after Wilson did not do what he expected, Nicklaus, always known for his candor on all matters golf, criticized the track as no longer the one he had grown up on. Then he built his dream club across town at Muirfield Village.

When another re-design was ordered in the 2000s, Nicklaus, by now one of the game’s leading architects, was not even consulted. The club opted instead for esteemed local designer Michael Hurdzan. Nicklaus, however, let it known through channels that he was willing to help out for free and the two parties were reunited. For the club’s centennial in 2016, with Scioto hosting the U.S. Senior Open Jack Nicklaus served as honorary chairman. Once again, he had missed the tournament.

Oakland Hills - South Course (1918)

Only the warm weather states of Florida, California and Texas have more golf courses than Michigan. Many of those started before Oakland Hills but none has garnered the same notoriety since. That is what happens when a parade of Hall of Famers lay the groundwork for your golf course. Oakland Hills is so famous that Dan Jenkins gives the fictional Bobby Joe Grooves his only major win in his novel, Slim and None.

The first was Donald Ross who when he saw the old Spicer, Miller and German farms for the first time in 1917 told Oakland Hills co-founder Joe Mack, “The Lord intended this for a golf course.” That’s setting yourself up to fail. Ross would later write, “I rarely find a piece of property so well-suited for a golf course.

Joseph Mack ran a printing house that catered to the nascent automobile industry. His partner Norval Hawkins was an accountant who became Henry Ford’s first general sales manager. Together they pried 46 fellow members out of the Detroit Athletic Club to form the Oakland Hills Country Club. Ross had the first of two planned courses ready for play in the summer of 1918. Walter Hagen was hired as the first professional for $300 a month, a open schedule and the profits from the golf shop. So before the grass was fully grown in that was two Hall of Famers.

Glenna Collett was undefeated for four years in match play, including a U.S. Amateur title at Oakland Hills.

Representing Oakland Hills, Hagen won the U.S. Open in a playoff at Brae Burn Country Club in Massachusetts in 1919 in a playoff with Mike Brady. Hagen used the opportunity to resign and recommended Brady be hired in his stead. In 1922, when Oakland Hills hosted the Western Open Brady became the first host pro to win the event. Also that year C. Howard Crane, a nationally known theater architect and club member, designed the commanding 17-bay clubhouse that was the second largest wooden building in Michigan.

Ross completed work on the second course in 1924 and they were now known as North and South. Just six years after it opened the South was hosting the U.S. Open and Bobby Jones was failing to repeat as champion, losing to Cyril Walker by three stokes after playing the par-four 10th hole in 6-5-6-6. In 1929 Glenna Collett won her fourth of six U.S. Amateur titles on the South Course as she was in the midst of a championship run even more impressive than anything Jones had done - 16 consecutive tournament victories in a four-year span.

With another U.S. Open on the horizon in 1937 Oakland Hills sought A.W. Tillinghast’s wisdom on possible improvements for the South Course. The future Hall-of-Fame architect shot back, “This course needs nothing to prepare it for the Open. What it needs is to be left alone.”

Robert Trent Jones showed no such restraint when he is invited to prepare the course for the 1951 U.S. Open. Ralph Guldahl’s winning score in 1937 had been sixteen strokes better than in 1924. In those days the host club was responsible for setting up the course, not the USGA, and Jones was given marching orders were to create the toughest course the players had ever tried to play. He took to the assignment with glee. In came the fairways, up went the rough. Seventy new bunkers were added to the number Ross had found sufficient.

No one broke par on the first day and the scoring average was 78.4. After three rounds no player had yet broken par and only Dave Douglas, a stylish pro from Delaware, matched the scorecard of 70. So when Ben Hogan shot 149 for the first two rounds he did not got to bed Friday night despairing of his chances. A 71 in the morning round pulled Hogan to within two strokes of leader Bobby Locke and he uncoiled a peerless 67 in the afternoon to win by two blows. Afterwards he said, “I’m glad I brought this course - this monster - to its knees.”

Both the South Course and Robert Trent Jones emerged from the 1951 Open as the torchbearers for unforgiving penal golf. Jimmy Demaret slipped the barb into Jones when he saw him, “Saw a course you’d really like the other day, Trent. You stand on the first tee and take a penalty drop.”

Pebble Beach Golf Links (1919)

It is because of the Transcontinental Railroad that Pebble Beach was built 50 years later. The so-called Big Four of the Central Pacific Railroad - C.P. Huntington, Leland Stanford, Mark Hopkins, and Charles Crocker - not only received box cars full of profits for building the railroad from the Pacific Ocean to Promontory Point, Utah to meet the Union Pacific but they received land grants as well. So much land the men formed the Pacific Improvement Company to manage the bounty.

In 1880 the company added additional land on Monterey Peninsula to their portfolio for about $5 an acre. They constructed the Hotel Del Monte and in 1897 built the Del Monte with polo enthusiast Charles Maud situating sand greens amidst cypress-studded hills; it has operated longer than any golf course west of the Mississippi River.

Samuel Morse orchestrated the conversion of Monterey Peninsula into Pebble Beach.

In 1915 the Pacific Improvement Company decided the time was right to get rid of its property on the peninsula. They hired Samuel F.B. Morse, the grandnephew of the inventor of the telegraph, to get the best price from developers. Morse was not a golfer, a horrible player in fact, but even he realized the first time he saw Pebble Beach that houses did not belong here.

After all, Morse reasoned, a world class golf course would make those other home lots that much more valuable. To sell his scheme to his bosses, Morse had two trump cards to appeal to their wallets - he would use sheep to maintain the course at no cost and recruit an amateur golfer to design the course for free.

Morse's plan to sell houses on Pebble Beach Golf Links counted on an ovine grounds crew.

The man Morse had in mind was Jack Neville, who already worked for the company as a real estate salesman and happened to be a five-time California State Amateur champion. Neville was handy with a mashie but he knew nothing of course design so he recruited a fellow state amateur champion who had been to Scotland, always a plus on an early American architect’s resume, to assist him with the newly named Pebble Beach Golf Links.

Neville may not have been paid but to hear him tell it he didn’t do much work either. As he related to the San Francisco Chronicle a half century later, “It was all there in plain sight. Very little clearing was necessary. The big thing, naturally, was to get as many holes as possible along the bay. It took a little imagination, but not much. Years before it was built, I could see this place as a golf links. Nature had intended it to be nothing else. All we did was cut away a few trees, install a few sprinklers, and sow a little seed.”

Neville walked the property and developed the figure-eight routing that is used today to make maximum use of the vaunted coastline. Pebble Beach is often cited for the relatively mundane inland holes but that reveals Neville’s genius design. By providing a breather from the thrilling clifftop golf on each nine, working back to the sea at the end of each nine he strikes the perfect balance for the player.

With Pebble Beach open for play in 1919, Morse indeed found the ideal buyer for the property - himself. Not a rich man, he had to form the Del Monte Properties Company to swing the deal but he was able to rule over Pebble Beach until his death a half-century later in 1969.

Neville’s design still required some tweaking, most noticeably on the 18th hole, which began life as a 379-yard par four. First the tee was relocated to the side of the 17th green on a rocky perch in the Pacific Ocean. Then British golf architect William Herbert Fowler lengthened the hole to 535 yards and golf had its most famous finishing hole.

Pebble Beach was now ready for its coming out party and Morse lured the USGA past St. Louis for the first time in its history to host the 1929 U.S. Amateur. The course’s biggest champion was Roger Lapham, a flamboyant shipowner and crack golfer who would go on to become mayor of San Francisco. He was also an influential member of the USGA executive committee.

The original 7th hole at Pebble Beach.

A team including 1904 and 1905 U.S. Amateur champion H. Chandler Egan and British architect Alister Mackenzie, who was working on nearby Cypress Point, worked on making the course championship-ready. And it would need all its defenses because Bobby Jones was planning to make his first West to compete.

Jones had won the past two U.S. Amateurs and four of the last five and was palying some of his finest golf in 1929. At the U.S. open earlier in the year at Winged Foot Al Espinosa had tied him after 72 holes of regulation play but Jones squeaked by in the 36-hole playoff by 23 strokes. The golfing legend arrived early in California and toured the Golden State setting course records, including at Pebble Beach where he shot a 67 in a tune-up.

Playing with course designer Neville, Jones was the co-medalist with Eugene Homans in the 36-hole qualifier. Neville failed to qualify with an 82 and 86 on the course he designed. In the first round Jones drew 19-year old Nebraska Amateur champion Johnny Goodman who had traveled to the Monterey Peninsula in a cattle car.

Goodman stunned the large gallery by winning the first three holes. Jones came back to tie on the12th hole but Goodman was not bowed and took the lead on 14 and parred out to complete the greatest upset in Amateur history; it was the first time Jones had lost an opening round match since he started entering the event when he was 14 years old. Goodman would lose his next match in the afternoon to Lawson Little Jr. but in 1933 he captured the U.S. Open at North Shore Country Club in Glenview, Illinois and so it is Johnny Goodman and not Bobby Jones who is remembered as the last amateur to win the United States Open.

For his part, Jones was not sure what to do with himself at the U.S. Amateur. He refereed a match the next day but his presence was too much of a distraction so he withdrew from the premises. He spent a few days at the course Mackenzie had designed - Cypress Point - and that experience would lead to the collaboration that a few years later would produce the only course in the American pantheon to rival Pebble Beach - Augusta National.

In 1947 Pebble Beach became a fixture on the PGA Tour when Bing Crosby brought his “Clambake” golf tournament up from Southern California. Crosby, who played near-scratch golf and had competed in both the United States Amateur and the British Amateur, had started the pro-am format in 1937 when he discovered how little money professional golfers were making. He stage the tournament at Rancho Santa Fe near San Diego, which was just up the road from his Del Mar Racetrack. Bing put up the entire first purse and wrote a check over to winner Sam Snead for $500.

In 1958, the tournament then known as the Bing Crosby Pro-Am was televised for the first time and it quickly became the highest rated regular PGA event of the year. Viewers tuned in each year to see one, the golf courses, two, the celebrities and three, the worst weather the pros would play in all year. “Crosby weather” invariably included wind and rain and snow was not out of the question, either. In 1960 Johnny Weissmuller who rose to fame as the world’s greatest swimmer before being the first screen Tarzan quipped, “I have never been so wet in my life.”

Each telecast would open with Crosby crooning “Straight Down the Middle,” a ditty penned by Sammy Kahn with music by James Van Heusen and introduce in a Hope-Crosby short called Honor Caddie in 1949. The Saturday broadcast would be devoted to the amateurs and Sundays would be left to the pros. Crosby hosted the show until his death of a heart attack walking off the 18th green of the La Moraleja Golf Course in Spain in 1977.

It took a few tries to get the most famous finishing hole in golf right.

In 1972 the U.S. Open came to Pebble Beach for the first time and Jack Nicklaus, who won the U.S. Amateur here in 1961, wrapped up a memorable win with a 1-iron into the par-3 17th that hit the flagstick and dropped five inches from the cup. Ten years later Nicklaus was witness to more drama on the same hole when Tom Watson holed a chip shot from deep rough for birdie to win the title. In addition to indelible Pebble Beach lore Nicklaus would also fill in the final piece of the puzzle of the course he always called “his favorite in the world.”

The original curse routing featured an odd detour away from the coastline after the fourth hole for the 156-yard fifth hole that some wags termed the “world’s only dogleg par 3.” It seems that back when Samuel Morse was in a hurry to liquidate the Pacific Improvement Company land he sold five acres on Stillwater Cove to William T. Beatty, a road builder from Chicago.

When he did a 180 on his development plans Morse was able to buy all the lots back but Beatty’s who hire renowned architect Julia Morgan to build a house there. Morse desperately wanted to retrieve the wayward five acres to complete his masterpiece but when the property finally came up for sale in the 1940s the one-two punch of the Great Depression and World War II had left the public course in dire financial straits and a California rancher named Matt Jenkins ponied up the $40,000 asking price.

For years the world’s best golfers detoured around the Jenkins property at number five. The historic house burned in 1956 but nothing changed. Finally when Mimi Jenkins died in 1995 at the age of 82 the family sold the Stillwater Cove plot to Pebble Beach for $8.25 million. Nicklaus was summoned to build a new fifth hole atop the seawall and Pebble Beach Golf Links was finally complete.