DELAWARE SPORTS IN THE 1920S

The 1920s. Ruth. Dempsey. Jones. Tilden. The Golden Age of American sports. In a poll at mid-century each was named the greatest performer ever to play his sport. For the first time America had national sports stars. Delawareans could listen to their exploits on their new radios and read the first national sports columns in Delaware papers, written by Grantland Rice and Harry Grayson. Non-Delawareans now eclipsed residents as sports heroes. And the legends came a’ callin’.

In golf Bobby Jones toured the Wilmington Country Club and the great British golfers Harry Vardon and Ted Ray played a popular exhibition at the Kennett Pike Club in 1920. Walter Hagen, Tommy Armour and Gene Sarazen appeared at Concord Country Club, a satellite of Wilmington Country Club, drawing thousands to their matches. The greatest American woman golfer, Glenna Collett Vare, competed in the annual woman’s invitational at the Wilmington course. And Joyce Wethered, who Bobby Jones called the greatest golfer he ever saw, man or woman, appeared in an exhibition before 700 at Wilmington.

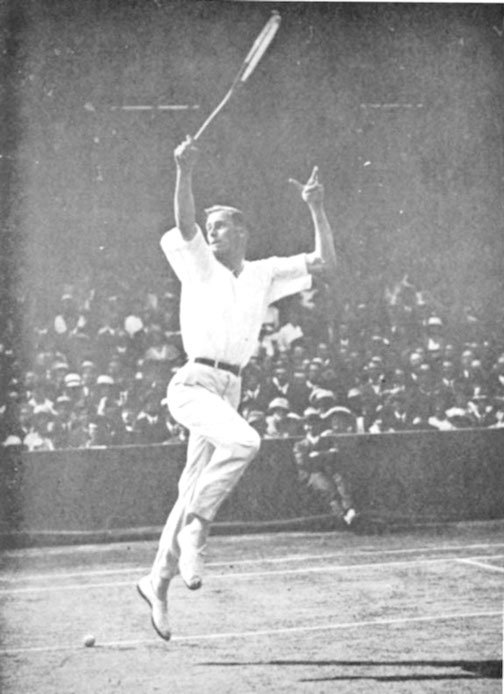

For tennis players the Delaware Open was strategically scheduled the week before the national amateur, usually held in Philadelphia. As a tune-up for the big event America’s best players competed on the Wilmington Country Club grass courts. Bill Tilden, holder of two Wimbledon and seven United States Open crowns, also had a Delaware Open trophy in his ample showcase. Big Bill was of “sturdy Delaware stock,” his father being a native of St. Georges. In the 1920s he played several times in Delaware, helping christen the new clay tennis courts at the Du Pont Country Club and staging several charity exhibitions.

Bill Tilden, the first great American tennis player, won two Delaware Open crowns. His father was a Delaware native.

Babe Ruth was a frequent visitor to teammate Herb Pennock’s farm in Kennett Square for some foxhunting and golf. The Babe even cracked up his car once on Route 1 near Wawa. The greatest star of them all played in Wilmington once, in a barnstorming game at Wilmington’s Harlan Field. When the Babe came into Wilmington for some shopping he would invariably be mobbed on his walks down Market Street.

The biggest sports hero in Delaware in the 1920s was boxer Jack Dempsey, the Manassas Mauler. The heavyweight champ first visited Wilmington in 1921 as a training break for an upcoming bout in Atlantic City with Georges Carpentier. Wending his way through the adoring crowds Dempsey professed a liking for the town. Three years later he found more reason to love Wilmington. Dempsey married actress Estelle Taylor, a Wilmington girl whose mother and grandparents still lived there, and the champ’s visits became more frequent.

Dempsey fights would be broadcast live over loudspeakers set up outside the newspaper offices and crowds of over 8000 would jam city streets for four blocks, listening and cheering to the blow-by-blow radio accounts. When Dempsey met Gene Tunney in Philadelphia it was estimated that more than 3000 Wilmingtonians took the train to join the crowd of 125,735. Jack Dempsey was a magical name in Delaware for years.

Jack Dempsey teaches his Wilmington bride, Estelle Taylor, a few boxing moves.

Professional sports in Delaware suffered in the shadow of the national sports explosion. In baseball there was minor league action available downstate, albeit by raw rookies, for much of the decade while in Wilmington the best ball was often played by “colored teams” like the Harlan Giants, starring Wilmington’s Judy Johnson, and the Wilmington Black Sox. The Hilldale Daisies from Philadelphia, who were the world champions of the Negro Leagues, often played home games in Wilmington. The top amateur leagues were the All-Wilmington and Twilight Leagues.

While there was less baseball to watch there was plenty to play. In 1921 Wilmington sported 15 baseball diamonds, three of which were reserved exclusively for the 6 women’s leagues in town. Even winter baseball was common in Delaware throughout the 1920s.

Football was the premier spectator sport of the age. It was not unusual for 20,000 people to see games across Wilmington on any given fall Saturday. Baynard Field, with two gridirons, could host four games on such days. Wilmington High School, which charged no admission, was the most popular eleven and could bring out 8000 rooters on game day.

The best semi-pro football teams were the Defiance Bulldogs and the St. Mary’s Cats. In 1925 the battle was joined when St. Mary’s broke a three-year Bulldogs’ hold on the state title by thrashing them 16-0 on Thanksgiving Day before 6500. St. Marys took advantage of a 75-yard fumble return and a 35-yard interception return for touchdowns to stun Defiance. St. Mary’s won on Turkey Day the next year as well to insure the Cats a place among Delaware’s best-ever local football teams.

The Defiance Bulldogs were the state champion footballers of the early 1920s and one of the last great semi-pro teams in the state.

On the whimsical side, casting, fishing-style, became a popular outdoor activity. The Delaware Anglers and Gunners Association began staging an annual baitcasting tournament each spring on the Washington Triangle in Wilmington. There were nine accuracy events and six for distance. By the end of the decade the Wilmington Casting Club was hosting invitational tournaments that attracted national distance and accuracy champions.

FIRST STATE SPORTS HERO OF THE DECADE: JUDY JOHNSON

In the first half of the 20th century third base was a waste area of sorts in major league baseball. The only three guardians of the hot corner named to the Hall of Fame from this era were Pie Traynor, Frank “Home Run” Baker and Jimmy Collins, hardly among the first rank of baseball immortals. Perhaps the greatest of all third basemen was a player hardly anyone saw - Judy Johnson.

William Julius Johnson was born in Snow Hill, Maryland in the last year of the 19th century. His father was a seaman and licensed boxing coach who brought the family to Wilmington for work in the shipyards when Willie was seven years old. He wore out the dirt playing ball at the field at 2nd and DuPont streets - now named Judy Johnson Park. He attended Howard High School for awhile but played no sports and dropped out as a sophomore to earn money for his family.

In 1918 Johnson began playing on Saturdays for the Chester Giants for $5 a game. In 1919 he was asked to join the Hilldale team from Darby, Pennsylvania. As the Hilldale Daisies became a charter member of the Negro Eastern League in 1922, Johnson became a full-time baseball player, earning $150 a month. With Hilldale his teammates remarked how much he looked like a former manager, Judy Gans, and Johnson became “Judy.”

In 1924 Johnson played in the first Negro League World Series, losing to the Kansas City Monarchs. The next year Hilldale and Johnson downed the Monarchs to capture the Negro World Championship, capping off a season when Johnson batted .392. Johnson - who never weighed more than 150 pounds in his playing career - went on to play with the Homestead Grays and the Derby Daisies of Philadelphia, both of which he also managed.

In the winter Johnson played in Florida and Cuban leagues - often against the white major leaguers he was excluded from competing against in the regular season. Johnson discovered Josh Gibson playing on sandlots and mentored the young catcher who would come to be known as the greatest hitter in Negro League ball. Winding down his playing days he joined the Pittsburgh Crawfords - the New York Yankees of the Negro National League. Besides Johnson, who served as captain, the team boasted Hall-of-Famers Gibson, Satchel Paige, Cool Papa Bell and Oscar Charleston. Not surprisingly, Johnson called the Crawfords, “the best team on which I ever played and the best ever I think in Negro baseball.”

Judy Johnson, playing for the Hilldale Daisies in the first ever Colored World Series in 1924. Johnson batted .364 in the Series and slugged .614 but the Daisies lost to the Kansas City Monarchs.

Leagues in 1971 and in 1975 Judy Johnson assumed his rightful place in Cooperstown - the sixth Hall of famer inducted from the Negro Leagues.

This came as a complete surprise to most Delawareans, few of whom had any notion a great ballplayer lived in their midst for 70 years. Delaware fell all over itself to rectify this slight. Johnson was the only unanimous choice in the first voting for the Delaware Sports Hall of Fame in 1976. The Wilmington Sportswriters and Broadcasters Association designated him their Athlete of the Year for 1975, an award heretofore reserved only for active athletes. Governor Pierre S. du Pont IV declared a “Judy Johnson Day” in Delaware. Johnson had a standing reservation at the head table of every sports banquet from Delmar to Claymont and many Delawareans came to know what many who knew Judy Johnson realized all along - he was a Hall-of- Famer off the field as well as on.

Judy Johnson was married for over 60 years to his wife Anita, who died in 1985. He followed in 1989 and their house in Marshallton at the junction of Newport Road and Kiamensi Avenue is now listed on the National Register of Historic Places. A statue of Judy Johnson, hands on knees, staring resolutely in anticipation of the next pitch, as imagined by Puerto Rico sculptor Phil Sumpter, greets visitors at Wilmington’s Frawley Stadium.

THE MARSHALL MARATHON

The Marshall money stemmed from the vulcanized fiber products churned out in the family mill in Yorklyn. T. Clarence Marshall was more interested in the plant’s steam power than the paper and he built his first steam automobile when he was 19 years old. Between 1910 and 1920 Marshall sold Stanley Motor Carriage steamers.

In 1921 T.C., an avid trapshooter, gathered some friends on his estate for a little tournament. Marshall set up eight traps on the line, along with two practice launchers. The format was unique; when most shoots consisted of at most 200 targets the Marshall shoot was a true marathon: 500 targets.

Wilmington businessman Isaac Turner won the inaugural Marshall Tournament by breaking 492 out of the 500 clays. The marathon format proved to be an exciting attraction and over the next decade the Marshall Marathon grew into the second largest trapshoot in the country behind only the Grand American. More than 500 shooters from across the country would travel to Delaware to test their skill on the hillside traps at Marshall’s estate. In addition to the 500-clay shoot the “Twinkling Star” night shoot proved extremely popular with the target blasters.

The Marshall Marathon in Yorklyn was the biggest trapshooting tournament on the East Coast for thirty years - in prestige, attendance and number of targets. The Auburn Heights property is now a Delaware state preserve.

With the marathon’s exploding growth came a dramatic increase in prize money. The purses offered exceeded $5000 - more than most professional golf tournaments of the day. With the best target shooters in the country on hand many world records fell over the years at the Yorklyn traps.

The Marshall Tournament was suspended during World War II but starting in 1946 two a year were held to “catch up.” But after 30 years the trapshoot just stopped. Tommy Marshall lost interest and his son was too busy with his travel business. The grounds and traps in Yorklyn stood silent but the tournament that grew from obscure beginnings into the nation’s second largest lived on. It was adopted by the South End Gun Club in Reading, Pennsylvania, still carrying the original Marshall Trapshooting Tournament name.

NATIONAL CHAMPIONS AT WILMINGTON HIGH SCHOOL

In Delaware Leroy Sparks is the Father of Swimming. Sparks was named physical-education director of the Wilmington YMCA in the early 1920s and he quickly became the foremost advocate of aquatic sports in the state. He founded the indoor state championships, which we would be a fixture on New Year’s Day for more than three decades, in 1921. He also started swimming as a varsity sport at Wilmington High School.

In 1926 Sparks guided the Cherry and White mermen to eight wins in nine dual meets against top Philadelphia schools. Convinced his swimmers deserved a larger stage Sparks launched a citywide campaign to send the Wilmington swim team to the national high school championships in Evanston, Illinois. Within two weeks the energetic Sparks raised the $1500 necessary for the trip.

His fervor was well-rewarded as Wilmington High swam to victory in the National Interscholastic Championships. Individually, Jack Spargo won the 100-yard breaststroke and James Fraser upset his teammate Franklin Holt, the Red Devils’ top sprinter, in the 100-yard freestyle. The Wilmington schoolboys also shattered a national record in the 200-meter medley relay with William Brown, Franklin Potter, Spargo and Holt.

The Prices Run pool was the most popular recreation spot in the city of Wilmington for much of the first half of the 20th century. This shot is from 1926.

After the 1926 school year Sparks left Delaware for Battle Creek College in Michigan where he would build up a national power over the next 35 years. He trailed behind him not only a legacy in Delaware swim history but in training as well. Sparks introduced a revolutionary energy-producing diet to his charges emphasizing carbohydrates and shunning steak.

His successor Tom Allen continued the controversial training regimen in 1927 and with Holt and Spago returning for their senior years Wilmington repeated as national champions, winning the title by three points even though the Red Devils were disqualified from one relay for swimming out of the lane.

The team was properly feted around Wilmington upon their return but graduation quickly brought a close to the Red Devil dynasty. Franklin Holt was the team’s star, swimming eight races in two days at the 1927 nationals; anchoring relays, winning the 100-yard freestyle and narrowly missing the 40-yard title. He went to Lafayette in 1928 where he broke many pool records as a freshman.

Desiring to return home he transferred to the University of Delaware, again setting pool records in practice, but had to sit out a season and dropped out of school. But that was not the last of Franklin Holt. After being away from school for nearly a decade he resumed his education in Newark and began to once again win swimming races for the Blue Hens.

LIFE IN THE MINORS

Matt Donahue could well be the best hitter of a baseball Delaware ever produced. But he came along at a time, between the World Wars, when there were more than 40 minor leagues in operation across America. With more than 300 teams rifling talent to only 16 major league squads many great baseball players never got a chance to showcase their talent in the big leagues.

Matthew Donohue earned 13 letters in football, basketball, baseball and track at Wilmington High School from 1911-15. After high school he played on many teams around Delaware and competed against major leaguers in the Shipyard Leagues during World War I as a member of Pusey and Jones.

Donohue started his professional career with Rochester of the International League, only a rung below the majors. He would climb no further. It was said of Donohue that “he could slash the apple but his arm was a trifle weak.”

In 1921, the 23-year old was a reserve outfielder for the Baltimore Orioles, considered the second best minor league team of all-time by MILB.com. He went 7 for 10 in the Little World Series that year.

For the next ten minor league seasons the hard-hitting Donohue averaged .331, never winning even a big-league trial. His minor league travelogue included Mobile, Des Moines, Kansas City, Seattle, and Elmira.

He sat out a couple of years in the late 1920s but staged a comeback in 1930 as a flyhawk for Wilkes-Barre in the New York-Pennsylvania League and made the all-star team by knocking out 202 hits for a .377 average. Still no calls from the bigs.

Perhaps the biggest headline Donohue received in the 1920s came from The Evening Independent in his adopted town of St. Petersburg, Florida in 1925 when he remarried his wife five years after the couple’s divorce: MATT DONOHUE WINS THE CAKE FOR HIS BRAVERY.

THE FIRST DELAWARE SPORTS MOVIE

The first sporting event in Delaware to be captured on celluloid was, of all things, a motorcycle hill climb. In the summer of 1922 more than 4000 speed fans gathered in a field in northern Delaware about 1/4 mile northeast of Smith’s Bridge near Granogue.

The Smith’s Bridge Hill Climb attracted motorcycle clubs from around the East, including several national champions. Also in the crowd was a motion picture director who filmed the primitive cycles roaring up the steep grass slopes above the Brandywine River.

His resulting movie began appearing shortly thereafter in area theaters as one of the “weeklies,” the short reels screened before the main feature.