DELAWARE SPORTS IN THE 1940S

The Golden Age of Delaware sports was the 1940s.

Baseball your sport? There were some years during the decade when as many as five Delaware towns had minor league teams. How about football? Wilmington’s minor league football team, which operated throughout the 1940s, was good enough to beat the Philadelphia Eagles. Down at the University of Delaware there were some students who matriculated on the Newark campus and never saw their team lose before they graduated.

Basketball? The Wilmington Blue Bombers were competing at the major league level - and winning championships.

Golf? Snowball Oliver, who graduated from the Wilmington caddy yards, was tearing up the PGA tour.

Boxing? Delaware sent forth a steady parade of title challengers and enjoyed the skills of Louis, Graziano, and Robinson in local arenas.

Horse Racing? A Delaware horse went to the post in the Kentucky Derby four years in a row.

Bowling? In one year Delaware sent more bowlers to the American Bowling Congress national tournament than all but nine other states.

Tennis? Wimbledon and U.S. Open trophies graced Delaware mantels.

And Delaware sports virtually ground to a halt for several years during World War II...

In 1937 there was not even an athletic field in Wilmington and there was no clamoring for teams. By 1941 Wilmington had minor league champions in baseball, basketball and football. Papers around the country acclaimed Wilmington as one of the leading sporting towns of its size in America. There were rumors of Wilmington hosting major league franchises in all those sports.

The sporting renaissance was fueled by du Pont family money. Lammot “Brud” du Pont, Jr. was a pioneer of this rebirth of pro sports with his Wilmington Clippers football team which operated through the decade. William du Pont’s showcase at Delaware Park was first class all the way, widely praised as a model operation in racing. Bob Carpenter Jr. kick-started the University of Delaware sports program, brought the minor league baseball Blue Rocks to Wilmington and even promoted boxing and auto racing.

World War II halted all this momentum. The University of Delaware stopped playing football, pro basketball and football sputtered, and Delaware Park closed. Transportation problems curtailed scholastic sports and many schools dropped varsity sports to concentrate on intramurals. Rock Manor Golf Club, which had typically done 35,000 rounds a year during the Depression, did less than 9000 during the war.

The sports that fared best in Delaware during the war were baseball and boxing. The Blue Rocks continued to operate and thanks to gas rationing and travel restrictions Delaware became a spring training site for the major leagues. The Philadelphia Athletics did their preseason preparation in Wilmington and the Toronto Maple Leafs of the International League set up camp in Milford. The sensation of the Maple Leafs in 1943 was one-armed outfield wonder Pete Gray who was cut by Toronto but later made the major leagues with the St. Louis Browns.

The Wilmington Ball Park was the envy of cities much larger than Wilmington.

In boxing heavyweight champion Joe Louis sold war bonds in a 3-round exhibition at the Armory. The champ used big gloves but was not coasting, saying, “I don’t want to take chances with those big guys.” Still, he sent his opponent to the canvas three times before the ref stopped the bout. Sugar Ray Robinson fought several times at the New Castle County Army Air Base and, in fact, was in New Castle with Louis when the Japanese asked for surrender in August of 1945.

Boxing fans could see Sugar Ray Robinson, whose record was once 128-1-2, in Deleaware during the 1940s.

After the war Delaware was ready to play. The first Delaware State Horseshoe Tournament was played in North Brandywine Park. The first Delaware Amateur golf tournament teed off at DuPont Country Club in 1945 with Pennsylvania invader Bob Davis of Harrisburg winning. Pari-mutuel betting was allowed on harness racing for the first time in 1946 and attendance at Harrington Raceway exceeded all expectations. Also in 1946 more than 200,000 swimmers used the five Wilmington city pools and the first Delaware State Swimming and Diving Championships drew 2000 to Canby Pool for 30 events. In 1948 came the first annual Delaware State Track & Field Championships at Wilmington’s Baynard Stadium.

There was plenty to see in Delaware sports as well in the post-war years. There was stock car racing at four tracks downstate and minor league baseball in Wilmington, Milford, Dover, Seaford and Rehoboth. In golf the Delaware Open brought PGA stars Gene Sarazen, Lew Worsham, Dutch Harrison and others to Rock Manor during its four-year run. Frank Stranahan, the famous weightlifting millionaire amateur won the event in 1948 with a two-day total of 138. And if that wasn’t enough sports fans could take special trains to race tracks at Bel Air, Havre de Grace, Laurel and Atlantic City and to see the Phillies or Athletics at Shibe Park.

But the Golden Age of Delaware sports was coming to an end, and fast. It was the age of television.

FIRST STATE SPORTS HERO OF THE DECADE: ED “PORKY” OLIVER

For want of a kinder fate Ed “Porky” Oliver might be remembered today as one of America’s all-time golfers instead of only Delaware’s best player ever. In the 1952 Masters Oliver equalled the tournament record but finished second to Ben Hogan who scorched the Augusta National course to a new mark by five strokes.

Earlier, in the 1946 PGA Championship final, then contested at 36 holes of match play, Oliver led Hogan 3-up after 18 holes. At the break between rounds Oliver headed for the lunchroom while Hogan went to the practice tee. In the afternoon Hogan shot 33 on the front nine and routed Oliver 6 and 4.

But it was the U.S. Open where Oliver suffered most. In the 1940 Open, at Canterbury Country Club in Cleveland, Oliver was among the leaders after three rounds of play. As a storm brewed from Lake Erie Oliver and his playing partners dashed to the first tee to start their round early. The official starter was still at lunch and there was confusion about whether the players could tee offbefore their assigned times. The players forged on.

Oliver finished with a 287 total, tied with two others for the lead, but he was disqualified for playing out of turn. The other players objected, insisting Porky be included in the playoff for the championship. It was no avail, the disqualification stood. Oliver was heartbroken. “It’s not just the honor of having a chance to win the Open,” he said in the locker room, choking back an occasional tear. “I need the money, and I need it badly.”

Oliver finished second so often that he earned the tag “America’s runner-up.” In two decades on the PGA tour Porky piled up 14 second place finishes and tied behind the leader another 9 times. He won 11 championships.

Born in Wilmington in 1915, Oliver got his start in golf as a caddie at the DuPont Country Club, earning $.50 to $1.00 per loop. He shortly went on to tote bags at the Wilmington Country Club where he anchored the Kennett Pike club caddy team in the Philadelphia District matches. Known as “Snowball” because of his propensity for hurling ice balls as a youngster, Oliver won two straight Philadelphia caddy titles, dominating more than 250 area boys. Before deciding on a career in golf he was a standout athlete at Alexis I. du Pont School, excelling in football, baseball and track.

Ed Oliver was one of the most popular golfers to ever play the PGA Tour - and but for better fortune almost one of the most successful.

Oliver turned pro in 1933 as the second assistant at Wilmington Country Club and quickly established himself as one of the longest hitters around. He played in money matches around the Delaware Valley with area pros and in 1936 captured his first professional tournament, the Central Pennsylvania Open. That year Oliver met tour pros for the first time at the Hershey Open and finished 14th out of 160 to take home $90.

Buoyed by his success three Wilmington Country Club members, Bill Denham, Simpson Dean and Sonny Baker, pooled $1000 to send young Snowball out on the winter PGA tour. Once on tour Oliver teamed with another rookie, Sam Snead, in profitable 4-ball matches. Oliver’s best finish was a third at the Miami Open where he won $300 but putting problems dogged him throughout his southern swing.

He bought nine different putters and discarded five. It was an incurable affliction. In his later years Oliver would call putting the bane of his career, lamenting that “it has killed me for over 15 years. I’ve usually had to play 63 golf to shoot 68.”

Back in Wilmington Oliver added victories to his resume in the Wood Memorial at Jeffersonville, Pennsylvania in 1937 and the South Jersey Open and a second Central Pennsylvania Open in 1938. It was at theSouth Jersey Open that Snowball Oliver served notice to his fellow professionals. Playing in a brisk Atlantic wind Oliver shot a final round 64, seven strokes better than any pro in the field. Veteran touring pro Leo Diegel called it “the greatest round I’ve ever seen in over 20 years of golf.” And Oliver did it with borrowed clubs.

After a stint as club professional at Hornell Country Club in New York state Oliver became a regular member of the PGA tour in 1940. His first tour victory came at the Bing Crosby Pro-Am in the fourth year of the popular Clambake with a 68-67 at Rancho Santa Fe Country Club. Among his amateur partners were Crosby himself and Johnny Weismuller, a.k.a. Tarzan, who remained lifelong friends. Oliver won the next week, too, at the Phoenix Open with a final round 64.

By the time the tour had reached Texas Oliver was a gallery favorite,renowned for his good humor and happy-go-lucky attitude. A San Antonio paper noted, “This Oliver is a comical fellow to watch on the course. With a battered felt hat mashed in some outlandish fashion around his cranium, he just tramps along, apparently without a care in the world, laughing and clowning. But, boy, oh boy! How he can crash that ball. He doesn’t seem any more worried about his missed putts than he does his ample waistline. Which is none at all judging by the way he can tuck away the groceries.” Indeed, his friends on tour tagged him “Porky” for his celebrated feats at the dinner table, melting the “Snowball” forever.

Then came the tragic lost U.S. Open at Canterbury, near Cleveland. Although devastated by his disqualification Oliver emerged from the incident a national celebrity. He was in great demand for exhibitions, given to approaching the first tee with a twinkling grin and asking innocently, “Is it all right if I start now?” He even won the next week at St. Paul, a victory he cited as his biggest thrill because it came against the same field he had just met in the U.S. Open.

Oliver won the 1941 Western Open, then considered one of golf’s most prestigious tournaments before being drafted in March. After a four-year stint in the Army he enjoyed his finest year in 1946, placing fourth on the money list with $17,941. The next year the 32-year old Oliver left the tour for a club job in Seattle at Inglewood Country Club. “I was the fourth leading money winner last year, yet when I got through paying my taxes and expenses I didn’t recognize my income. I’m a family man with three kids and long overdue to settle down.”

Oliver played some of his best golf in the Northwest. He won five straight minor professional events, the PGA Tacoma Open and brought home $5000, one of his biggest paychecks, by capturing the Phillipine World Open. By 1951, however, Oliver was a full-fledged member of golf’s “Gypsies” once again. His fine play on tour earned him berths on the Ryder Cup team in 1951 and 1953. In 1952 Oliver again finished runner-up in the U.S. Open, four strokes back. Of little consolation was a fifty-foot putt Porky holed on the last green to nose nemesis Hogan for second place.

Oliver’s career came to an abrupt end in 1960 when a lung was diagnosed as cancerous. When he left the tour he was the 13th all-time money winner in golf history. As his condition deteriorated “Porky Oliver Days” were held across the country, in many sports besides golf. Early in 1961 his old friend Sam Snead came to Wilmington for an exhibition summing up the feelings of many of the tour professionals when he stated that, “Porky’s the only person in the country I’d do this for - play for nothing.” The event was rained out and re-scheduled for September 30 but Oliver passed away ten days before his final reunion with Snead.

Porky Oliver was eulogized as “the greatest athlete to represent Delaware in national and international competition.” Perhaps his most fitting epitaph came from Snead who said, “On a given day Porky could beat any golfer who ever lived. But golf to Porky was just a means to have fun.” Years later the Green Hill Municipal Golf Course in Wilmington was renamed in honor of Ed “Porky” Oliver, the golfing star who had narrowly missed capturing each of America’s three greatest golfing prizes.

LOST DREAMS

World War II wreaked havoc with many athletic careers, big and small. In Delaware, Casimir Klosiewicz was an Olympic caliber weightlifter in 1940, a 165-pounder able to hoist 720 pounds in the three Olympic lifts. Klosiewicz, a one-time Wilmington High School grid star, had been lifting since 1936 as a member of the Delaware Bar Bell Club.

The Olympics were not held during the war years of 1940 and 1944, years when Casimir was out-lifting everyone. Klosiewicz joined the Signal Corps of the Third Army and landed in Europe in the Normandy invasion. In 1948 Klosiewicz, now 27, could manage only a third place in the 148- pound class and failed to make the United States team. That was the last try for Klosiewicz who retired to the Wilmington post office.

“...OF WILMINGTON, DELAWARE”

Whenever an athlete performs well in a national or international competition the reporting of his/her hometown brings desired notoriety around the country and invariably boosts civic pride. As a desirable place to live Delaware has always attracted transplants of all sorts, including athletes. Recent examples include boxing champion Michael Spinks and golf’s U.S. Open winner Laurie Merten, both of Greenville, Delaware.

The first of these champion transplants to settle here was Marion Zinderstein, a Massachusetts tennis star. Miss Zinderstein won the national doubles title as an unranked team in 1918. Only seeded fourth the next year she won again. A third national doubles crown came in 1920 and Zinderstein finished runner-up in singles play as well.

Also in 1920 Miss Zinderstein came to Delaware and won the state woman’s title - and a husband as well. Marion married a Wilmington banker named John Jessup. Mrs. Jessup won the Delaware tournament in 1921 and 1922, retiring the trophy and becoming the first Delaware resident to win the state title. A baseliner who seldom came to the net, she also won her fourth national doubles championship, teaming with 16-year old sensation Helen Wills.

After a brief retirement Mrs. Jessup was back representing Wilmington in competition in 1924. Always a standout indoor player she won both the national singles and doubles and became Delaware’s first female Olympian, winning the silver medal in Paris in the only mixed doubles competition ever held. Mrs. Jessup began fading from the national scene in the mid-1920s as she devoted more time to her family but she continued to win Delaware titles into the late 1930s.

Never did Delaware receive more national press from its immigrants than the 1940s. In 1945 Bill Talbert, America’s #2 tennis player, moved to Brandywine Hills in Wilmington. Although a Delawarean for only a little over a year Talbert was splashed across the sports page in the middle of a run that would see him collect 17 wins in 21 tournaments. Announced as “...of Wilmington, Delaware” Talbert, a diabetic, reached the finals in 97 of 103 events in singles, doubles and mixed doubles. He went on to win 8 national doubles tournaments, was ranked in the Top 10 thirteen times and was elected to the Tennis Hall of Fame in 1967.

In golf Betty Bush, wife of Brandywine Country Club pro Eddie, represented Delaware in the United States Open and reached the match-play finals of the Canadian Open in 1948. But unquestionably the greatest Delaware import to move to the Diamond State in the prime of her career was Margaret Osborne, a native Oregonian. She came to Delaware as a 24-year old in 1942 at the invitation of William du Pont, Jr., who offered his private courts at Bellevue to practice for upcoming big events in the East. Du Pont thought that the Osborne and another guest, Louise Brough, both hard-hitting aggressive net players, would make an excellent doubles team. His acuity was well-placed - the two would win a phenomenal nine consecutive national doubles titles, twelve in all. They tasted defeat in only a handful of more than 300 matches.

Miss Osborne found more than a doubles partner at Bellevue. She married Mr. du Pont in 1947. For the rest of her career one of the world’s greatest woman’s tennis players picked up her mail in Delaware. She won three consecutive U.S. Open championships in 1948, 49 and 50. A master of lobs and spins, she was ranked number one in the world for those three years.

Mrs. du Pont also won Wimbledon in 1947 and the French Open in 1947 and 49. Her international Wightman Cup record was a phenomenal 18-0, with ten wins in singles and eight in doubles. Fourteen times she was ranked in the Top 10 among tennis players, at age 40 she was still #5. She retired with 37 major titles; only Margaret Court, Martina Navritilova and Billie Jean King ever won more. In 1967 Mrs. du Pont was elected to the National Tennis Hall of Fame along with her longtime doubles partner Louise Brough.

A TRULY OLD MASTER

When the Wilmington Country Club formed in 1901 Joshua Ernest Smith was already 51 years old. No matter, he still had four decades of golf left in him. In 1944, at the age of 94, Smith holed his last putt, saying he reckoned it was time to leave the game to the younger fellas. Thus ended one of the most spectacular careers in early American golf.

A lawyer by trade, Smith also stopped practicing law in 1944 after 67 years at the bar. In 1880 he drafted Delaware’s famous corporation law. Smith served as judge advocate general under five governors and was a member of the Delaware National Guard for 24 years. He was appointed a Brigadier General by Governor Denney. He began playing golf in his forties at the Delaware Field Club, quickly becoming the best of the three dozen or so golfers who played tournaments regularly at the Elsmere grounds. He was the first player to break 100 and was assigned a club handicap of -13. Smith captained the club’s first golf team which represented Delaware in interstate matches. Against a club from Philadelphia Smith defeated Hugh Wilson, who would later design the world-famous Merion golf course.

General Smith was one of the first three subscribers to the Wilmington Country Club when it formed in 1901. He continued to play fine golf at the new Kennett Pike course until his career really hit its stride - at age 70. The General won all five national senior tournaments he played in for golfers 70-75 years of age. It was just a tune-up.

Upon reaching 75 General Smith played in seven more national championships for golfers 75 and over. He won six. At the age of 83 he posted an 88 in tournament play. He retired as America’s best “experienced “ golfer.

Well into his 90s Smith hosted an annual dinner for the Wilmington Country Club caddies each Christmas. The General maintained no recipe for his great longevity, advising inquisitors just to “stay healthy.” He smoked 20 cigars a day but boasted that he “never knew what whiskey tasted like.”

A widower late in life, Smith donated the trademark Japanese cherry trees in Brandywine Park as a monument to his wife, Josephine Tatnall Smith. He also gave money for the Italian-inspired fountain in the park in 1931 which became known as Josephine Gardens.

Smith was a fixture in Wilmington Park, seated in Box A-11 opposite first base. In his later years the General often boasted he could count the number of Blue Rocks’ baseball games he had missed “on one hand.” Among his last words before slipping into a coma shortly before he died at age 98 was a request for the Blue Rocks score.

SPORTS BOOM AT THE BEACH

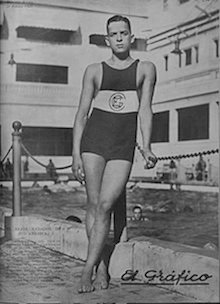

The 1940s witnessed the emergence of Rehoboth as a sports center in Delaware. In 1941 promoters started an ocean swim from Dewey Beach to the Hotel Henlopen which became known as the Delaware Mile. World War II interrupted the Labor Day event and when it started again organizers were surprised at the strength of the field, headed by 400-meter former Olympic champion Alberto Zorilla of Argentina.

Zorilla traded championships in the Delaware Mile in 1947 and 1948 with 1941 winner Willard McConnell of Wilmington. With such stars on hand top collegiate swimmers began spending Labor Day at Rehoboth and the ocean swim grew into nine events over two days, including women’s divisions. By the mid-1950s the Delaware Mile had been re-named the International Swim Races. There was such an influx of aquatic talent, especially from the Washington DC area, that a separate division had to be established for the overwhelmed Delaware swimmers.

Argentine swimming star Alberto Zorilla, who won a golf medal and set an Olympic record in the 400 meter freestyle in 1928, was a regular winner of the Delaware Mile offshore swim.

Along with the growth of the ocean swim minor league baseball came to Rehoboth in 1947. A brand new Rehoboth Beach Baseball Park was built which hosted outdoor boxing and auto racing as well as baseball. With the passing of the Rehoboth Beach Sea Hawk baseball team after 1949 the ball park was converted into a 1/4 mile banked track. It was the fastest clay track in the East and the races, with 20-lap features, attracted capacity crowds. In the winter the Rehoboth Lions hosted the 8-team Atlantic Coast Basketball Championships.

These sporting ventures were successful enough that the Delaware Greyhound Racing Association formed with the intent of building one of the East’s premier dog racing tracks at the beach. The plant was planned for the E. Thornton Hobson farm less than three miles from the boardwalk. For three years promoters of dog racing tried to get approval from the Delaware legislature. But when it failed the project was abandoned and the sports boomlet at the beach began to subside. Rehoboth returned to being “America’s Family Playground” and promoters of spectator sports drifted elsewhere.

THE SPORTSMAN: WILLIAM DU PONT, JR.

No one ever built a greater sporting resume in Delaware than William du Pont, Jr. Horse racing, tennis, golf - he brought national recognition to the state for his efforts in all three sports.

The great grandson of the founder of the chemical conglomerate, William was born in the bucolic horse country of Surrey, England in 1896. Schooled in America, he was active in tennis, soccer and marksmanship. In horse racing he became an internationally recognized authority on the design and construction of steeplechase courses. He was architect of more than two dozen courses around the world, including the National Cup Course on his 11,000-acre estate at Fair Hill, Maryland.

At his primary residence at Bellevue in north Wilmington du Pont maintained a 1 1/8-mile oval and six training tracks. His quarter-mile indoor track was the most modern in the nation. His Foxcatcher Farms horses raced under sapphire blue silks with a gold fox on front. Five Foxcatcher horses started in the Kentucky Derby; Dauber and Hampden were the most successful Delaware entries ever with a second and a third.

He favored fillies, especially those that could whip the boys. His best was Fair Star, a Pimlico futurity winner and Fairy Chant who won the Beldame twice. Du Pont would typically rise at 4 a.m. to train his horses personally before heading downtown to take the reins of the Delaware Trust Company.

William du Pont was the leader of the horsemen who brought pari-mutuel racing to Delaware. He designed Delaware Park and oversaw construction of the plant that brought major league sports to Delaware. Ironically, after sheperding Delaware Park into existence du Pont missed the grand opening. He decided to go to Aqueduct to see his star Rosemont run, nursing a broken collarbone while schooling a jumper at Bellevue the day before.

If there was a sports movement going on in Delaware in the 1940s chances are William du Pont, Jr. was likely part of it.

Only his tremendous contributions to horse racing could dwarf what du Pont did for tennis in Delaware. The courts at Bellevue evolved into one of the greatest private tennis complexes ever. Du Pont employed three resident tennis pros and hosted international tennis stars at his famous “tennis Sundays.” He married one, Margaret Osborne, in 1947.

If you played tennis in Delaware after World War II chances are you played on a court William du Pont had a hand in. He was president of the Delaware Lawn Tennis Association for eight years, building a nationally recognized junior tennis program. He contributed half the cost of more than 60 all-weather tennis courts in Delaware. He also gave money to the Wilmington Park Department for construction of public courts.

Du Pont served as president of the Wilmington Country Club and in 1958 donated 108 acres, including 15 golf holes, to the city of Wilmington. The following year he gave another 15 acres to assure the city an 18-hole golf course, now known as Porky Oliver Golf Club.

William du Pont Jr. was committed to advancing the thoroughbred breed and perhaps his greatest recognition in the racing industry came after his death which accompanied the dawn of 1966. Six weeks later his stable of 51 thoroughbreds was put up for auction. Bidders spent a record $2,401,300 for Mr. du Pont’s string of Foxcatcher broodmares and stallions, some of the finest ever bred.

So, it’s time to add up what Delaware sports enthusiasts owe to William du Pont Jr. Ever place a bet at beautiful Delaware Park? Played a round of golf at the only public golf course within Wilmington city limits? Hit tennis balls at a Delaware state public court? Picnicked or ridden the horses at Bellevue State Park? Thank you William du Pont, Jr.

DELAWARE’S FRANK MERRIWELL

One of the most versatile athletes in Delaware history was Willard McConnell, a banker by trade and sportsman by avocation. McConnell was reared in Delaware City and first made his mark in Delaware sporting circles on the softball field when he won a state record 21 straight games. When he took up duckpin bowling he ruled the lanes for nearly 20 years. McConnell’s high game of 278 is one of the highest on record.

At the age of 23 he jumped into the Chesapeake & Delaware Canal on a lark and swam 15 miles in six hours and 18 minutes without any preparation. He then got it in his head to swim from Cape May to Rehoboth and was in the water 8 hours and 26 minutes when exhaustion hit and he was forced to abandon his quest only 1.5 miles from shore. In 1941, at the age of 37, McConnell won the first Delaware Mile Swim in the Atlantic Ocean at Rehoboth Beach.

His marathon swimming career was interrupted when he took up golf, which chewed into his training time. McConnell became perennial club champion at Kennett Country Club but still got enough water time to set a record in the Delaware Mile with a clocking of 21:57. When he approached his 50th birthday he began working on a lifelong goal to swim from Delaware to Florida.

Golf, however, became McConnell’s primary sport in his later years. He won five Delaware senior titles and qualified for the United States senior championship. At the age of 58 he shot a 62 at Kennett to tie the course record, although the March round was played with winter rules and temporary tees. The “Old Gray Fox” won the club championship at Kennett 18 of 23 years before succumbing to a heart attack on the Rock Manor Golf Course in 1969 at the age of 65.