DELAWARE SPORTS IN THE 1950S

Major league crazy.” That best describes Delaware sports in the 1950s. Bob Carpenter, Jr. was slow to appreciate the power of television but by 1950 he was declaring that he intended to broadcast as many Phillie games as he could fit on the air. There was no need to continue going to low-class boxing matches when there were better ones every night on the tube.

And so spectator sports died in Delaware. The Blue Rocks disbanded in 1952. Wilmington Park, the envy of every minor league town in America a decade earlier, no longer could support itself with the odd rodeo, wrassling show, or polo match and it was razed in 1955 after only 15 years of use.

The highlight of the 1950s was the new Brandywine Raceway in northern Wilmington in 1953. The $2,500,000 harness track was a success from the first post time. Head Pin flashed under the wire to win the first race in 2:10, returning $7.90 to win and by closing night The Big B handled $6,000,000 in its 20-night meet. Delaware Park was hardly hurt by its new neighbor. The Stanton plant averaged 15,017 fans in 1953, including a one-day record attendance of 35,473. Horse racing was the major sport in Delaware.

Another success story was the annual high school all-star football game, founded by Bob Carpenter and Jim Williams, begun in 1956. The first Blue-Gold charity game matching the best players from upstate against the downstate stars pulled 6594 to Newark to raise $17,000 for the Delaware Foundation for Retarded Children. It has gone on to raise over two million dollars. Few states are blessed with such a worthwhile sporting institution as the annual Blue-Gold football game.

The Delaware State Golf Association formally organized in 1952 with eight clubs and a series of tournaments for men, women and seniors. Al Dollins, president of the DSGA, won the first “official” Delaware Amateur, then contested at match play, 2 and 1 in the 36-hole final over Ronnie Watson.

Little League baseball was already in 37 states when it came to Delaware in 1951. The Wilmington Optimists was the first league organized with games at the park on New Castle Avenue and New York Avenue. Bus Zebley was instrumental in keeping the fledgling Little League going, umpiring all the games and calling time to do a little coaching if needed. If kids weren’t playing baseball they could be found at the swimming pool. A string of suburban pools dotted the outskirts of the region and peaceful summer evenings in many neighborhoods were routinely pierced by the shouts from swim meets.

There was a suburban exodus in New Castle County in the 1950s but the new suburbanites found few recreation areas waiting for them. There was only one public golf course in the state and developers outpaced the builders of parks. What organized recreation existed was managed by local sporting stores. That was soon to change.

FIRST STATE SPORTS HERO OF THE DECADE: DAVE NELSON

Dave Nelson came to Delaware in 1951 from the University of Maine at the age of 30. In four years with the Black Bears he had clawed out a 21-6-4 record while tinkering with a new offensive scheme. His first three years in Orono Nelson used the single wing and his final year he employed the T-Formation, both offenses gleaned from his days as a University of Michigan backfielder. He brought an entire new offense to Newark, one he said, “must have on every play the look of a run and the threat of a pass.” Nelson had built a reputation for stressing tackling and defense but his first spring practice at the University of Delaware was devoted totally to offense: goal-line blocking and timing with his Winged-T offense.

Although he inherited precious little talent, a special Korean War provision enabling freshmen to play gave Nelson a field general he would rely on for his first four years - Don Miller. With Miller at the controls Nelson’s new-fangled offense began driving Delaware to national prominence once again. After a 19-7 win over Kent State in the 1954 Refrigerator Bowl win in Evansville, Indiana - “the refrigerator capital of the world” - Nelson seemed ready to leave Newark for the “big time.”

His first offer came from Indiana University to become Athletic Director, a post he also manned in Newark. But Nelson, respectfully called “The Admiral,” wasn’t ready to leave the sidelines just yet. Over the years Nelson would be mentioned in connection with jobs at Harvard, Baylor, Pittsburgh, Colorado, Florida and the Los Angeles Rams. “It isn’t important to me,” explained Nelson on why he shunned the big schools. “The game’s the thing. I get as much satisfaction out of beating Connecticut or Rutgers as I would out of beating Illinois or Minnesota if I were coach of Michigan.” And so he stayed in Newark and built a legendary career at Delaware.

Dave Nelson brought the Winged T to First State gridirons.

In 1957 Nelson published Scoring Power With The Winged-T Offense, co-written with ex-Michigan teammate and Iowa coach Forrest Evashevski. The book contained over 300 detailed diagrams and action photos based on the offense Nelson devised at Maine in 1950. When Evashevski went to two Rose Bowls with the Winged-T in the late 1950s Nelson was acclaimed as one of football’s great offensive minds. Marv Levy, who would go on to Super Bowl infamy as coach of the Buffalo Bills, was named coach of California in 1959 and cited Coach Nelson as his greatest influence.

Nelson began to reach his greatest coaching success during the same era. His teams won the Lambert Cup, symbolic of Eastern small college supremacy in 1959, 1962 and 1963. The 1963 Blue Hens, Nelson’s greatest eleven, went 8-0 and were voted the national small college champion by United Press International. Back in 1957 Nelson was chosen as a member of the NCAA Rules Committee, at age 36 the youngest on the board and also from the smallest school. In 1961 Nelson, became head of the Rules Committee. And by 1967 Nelson was ready to sacrifice his life on the sidelines for his administrative duties with the NCAA and as Athletic Director at the University of Delaware.

Nelson left coaching after 19 years with an overall record of 105-48-6. At Delaware in 15 seasons he won 84 games, lost only 42 and tied two. Nelson was 45 when he retreated from the coaching wars, only five years older than his hand-picked successor, Tubby Raymond. For the rest of his career he resisted the occasional overture to return to coaching andoversaw the burgeoning Delaware athletic program, both at the varsity and intramural levels. In 1991 came the richly deserved election to the National Football Foundation College Football Hall of Fame for Dave Nelson.

PASSING THROUGH

Delawareans had many a chance to see embryonic legends and say, “I knew him when...”...

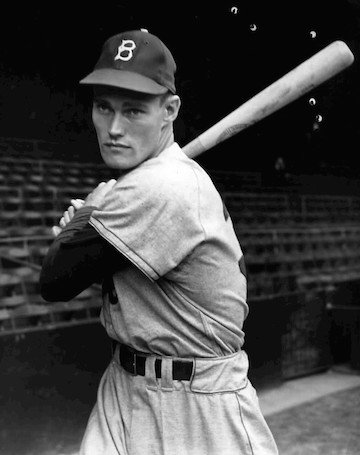

The Rifleman. He didn’t make much of an impression on Delaware fans as a low-scoring forward for the Wilmington Blue Bombers but the wisecracking Kevin Connors was always a favorite with the local sports scribes. Connors also played a little professional baseball and when he manned first base for Los Angeles one summer he began picking up bit parts in movies, usually as an imposing bad guy. The next time Connors, now known as Chuck, came to Wilmington it was in Pat and Mike at the Loew’s Theatre in 1952. Connors would go on to even greater fame as the fast-drawing, slow-burning Lucas McCain in television’s The Rifleman.

Chuck Connors played major league baseball and minor league basketball for the Wilmington Blue Bombers before becoming The Rifleman on television.

Say Hey. In the disintegrating days of the Wilmington Blue Rocks in 1950 the few loyal fans received one final treat before the team dissolved two years later. Willie Mays, the first black player in the Interstate League, played before 1663 fans in Wilmington Park as a Trenton centerfielder. Willie went 5-9 in a doubleheader with two doubles.

Followers of the Negro Leagues also had a chance to see Jackie Robinson cover shortstop for the Kansas City Monarchs as a youngster out of UCLA in 1945 and a skinny 17-year old infielder play several games in Wilmington Park in 1951 with the Indianapolis Clowns. His name was Henry Aaron.

The Softball Player. Bill Bruton was born and raised in Panola, Alabama but came to Wilmington during the war in 1943. For recreation he played catcher on a local softball team. Although he played no baseball in Delaware, Judy Johnson recommended him to a Boston Braves scout, who signed him for the National League club. Bruton could not even make his high school track team home in Alabama but soon he was breaking minor league base stealing records. When he reached the majors he led the league in steals his first three years. Bruton relocated to Milwaukee with the Braves but before he left he took a bit of Delaware with him - he married Judy Johnson’s daughter.

The Doctor. In 1952 Dr. Jack Ramsey, then 27, was named basketball coach for the Mt. Pleasant Green Knights. It was Ramsey’s second coaching job in a pilgrimage that would stretch all the way to the Portland Trailblazers and the Hall of Fame. At Mt. Pleasant High School Ramsey, who taught English and Social Studies as well, inherited only one player from a 6-14 team. He nonetheless forged three winning seasons with the Green Knights, going 40-18, before returning to his alma mater, St. Josephs, to build a program of national reputation. Ramsey was 234-72 at the collegiate level and won 834 NBA games, the second most ever.

The Stilt. Almost from the time he graduated elementary school Wilt Chamberlain was the most famous basketball player in America. In 1954 he came down from Philadelphia to play in a schoolboy game at the Walnut Street YMCA in Wilmington. Four years later, after leaving Kansas University early, Wilt played here again as a member of the Harlem Globetrotters. Performing in the Salesianum gym before 1900 Chamberlain led all scorers with 19 points, mostly on stuffs. It was not a history-making night - the Trotters won again.

Wilt Chamberlain played on Delaware basketball courts in the 1950s both as a schoolboy phenomenon and a member of the Harlem Globetrotters.

The Speedster, human-powered. Charley Jenkins, Olympic gold medal winner in the 400 meters at the 1956 Olympics cooled his heels for a year in Delaware when he spent 8th grade at Howard High School, living with his aunt when his mother was ill.

The Speedster, motor-powered. Mario Andretti is considered the most versatile driver of all time, having won championships with all types of racers from Indy cars to Formula One machines. Andretti cut his teeth racing “big cars” on dusty tracks up and down the East coast, one of which was Harrington Race Track.

The Rookie. Jake Wood came and went to Delaware State almost before the registrar could record his name. Wood left the Hornet baseball team after his freshman year and the speedy second baseman was next seen as a rookie in 1961 igniting one of the strongest offensive teams in history at the top of the Detroit Tiger line-up. Wood played in every game, scored 96 runs, stole 30 bases and led the American League in triples with 14. But just like at Delaware State the mercurial Wood would soon pass from the scene, never enjoying anything like the success of his rookie year.

The Recruit. In his long career at the University of Delaware who was Tubby Raymond’s most famous recruit? That would be Carl Yastrzemski, who was anxious to come to Newark and play for Raymond’s baseball team in the 1950s. Yaz went so far as to come down from Long Island and travel with the Blue Hens to a game at Ursinus College, where he watched the game from the bench. Alas, an academic problem kept Yastrzemski from enrolling at the University of Delaware and he took his future Hall-of-Fame bat to Notre Dame.

THE BRANDYWINE CANOE SLALOM

Here’s one that is certain to win a few bar bets. What Olympic sport started in America in Delaware? Kayaking.

Bob McNair, the founding force behind the Buck Ridge Ski Club in 1945, literally wrote the book on Basic River Canoeing. In 1954 McNair and Buck Ridge started the Brandywine Canoe Slalom, the first event of its kind in the country. About 150 canoeists and kayakers from as far away as Toronto came to test the boulder-strewn waters on the historic river. There were divisions for men and women and one and two-person canoes and kayaks.

The Brandywine Canoe Slalom, held each April, quickly developed into one of Wilmington’s most popular springtime events. Up to a thousand spectators would line the banks of the river in Brandywine Park along the course that ran for 200 yards south from the Washington Street bridge.

The first inter-club canoe slalom races started on the Brandywine River in the 1950s.

A canoe slalom is like a ski slalom down a mountain, only trickier. Contestants had to not only pass through gates hung from wires stretched across the Brandywine but they had to pass in the proper direction - which sometimes meant having to battle upstream. Contestants could also be required to navigate gates in reverse. The craft entered the river one at a time and the race was against the clock.

In 1972 white water kayaking achieved Olympic status and the rest of America caught on to the excitement Delawareans had enjoyed for nearly twenty years. The Brandywine Canoe Slalom was, at that time, a qualifying event for national and international competitions. For several years the course was designed by Mark Fawcett, a Wilmington area canoeist who raced three times in the world championships between 1965 and 1969. He managed the United States Olympic team in 1972.

The Brandywine Canoe Slalom passed from the Delaware sporting scene in the late 1970s. But for a quarter of a century it provided Wilmingtonians with world-class competition of the sort the Tour DuPont would bring to Delaware a decade later.

SALESIANUM FOOTBALL

High school football in Delaware will never be confused with Ohio or Texas or even Oregon for that matter. Wilmington High School, known simply as “High” in the state, drew the biggest football crowds in Delaware for the first half of the century. The rivalry between the Cherry and White and Chester High School was one of the oldest in America, dating back to 1891 when few secondary schools were playing ball and neither had any in-county gridiron foes. The two played for 53 years, often with as much action in the stands as there was on the field. Enemy fans were typically chased out of town and often wound up chatting with the local gendarmes. Chester won the first meeting 6-0 and the last battle 6-0 in 1944, when the series ended so Chester could schedule Delaware County schools. Chester was on the long end of the rivalry 31 wins to 23.

For many decades high school football in Delaware meant Salesianum. The school’s legacy in the sport began modestly in 1921 with the stated objective of building “a team capable of coping with any school in the country.” Lofty aspirations for a school founded only 18 years earlier with a student body of 12.

That first year Salesianum went 3-3-1. The first win came in the second game, a 7-0 whitewashing of New Castle High. Later that year Sallies held state football power Wilmington - bigger and more experienced - to a 0-0 tie before 8000 fans squeezed into 18th and Van Buren streets. But success did not come quickly. There were but 11 wins in the first 38 games.

Salesianum became a charter member of the Philadelphia Catholic League in 1923 - a school of 180 squaring off regularly with institutions of 1800 and more. The Wilmington school held its own in this competition and even claimed a share of the championship in 1934 before dropping football in 1938. Football resumed after World War II and Salesianum once again took up chase of its dream.

National status came in the 1950s with the arrival of coach Dominic “Dim” Montero, a former Sallies’ All-State lineman. In ten years Montero lost only ten games, piling up 70 wins and three ties. While in-state schools became focused on the new conferences that were finally allowed to form Salesianum played an increasingly tougher out-of-state schedule. Never would a Delaware scholastic eleven enjoy a period like this. Sallies games were carried exclusively on local radio and games were played conspicuously on Friday nights - a rarity in Delaware. In 1957-58-59 Salesianum went undefeated and molded a then-state record 29 consecutive wins. College recruiters routinely harvested Sallies players; five played on the 1960 University of Minnesota Rose Bowl team.

By the mid-1960s enrollment had grown to more than a thousand. In 1964, in his penultimate year, Montero was named National Catholic Coach of the Year. But its monopoly of Catholic schoolboy talent in Delaware was ending. St. Mark’s High School opened south of Wilmington and siphoned enough warriors from the old school on 18th & Broom to win state championships of its own in the 1970s.