1961-ON courses

Sun City - North Course (1960)

Leave my family and community and go retire in the middle of the desert? With a bunch of other old people? Who would do such a fool thing?

Those were the questions the operators of the Marinette Retirement Community were asking themselves as they prepared for a weekend open house in the world’s first planned retirement community on January 1, 1960. There had been a blizzard of national advertising and billboards to introduce the revolutionary concept but there were nagging doubts. Would anyone actually show up? Of course if this thing was a flop developer Del Webb could afford to take the hit.

Delbert Eugene Webb had not had too many swings and misses in his sixty years. He was born and raised on a Fresno, California fruit farm before dropping out of high school to work as a carpenter’s apprentice. When he was 28 years old Webb contracted typhoid fever and moved to Phoenix, Arizona to recover. At the time the capital city boasted fewer than 40,000 residents.

Webb went into the construction business and prospered enough to participate in the purchase of the New York Yankees in 1945. Mob boss Bugsy Siegel picked Webb’s firm to build his landmark Flamingo Hotel and Casino in Las Vegas in 1946 and he later became an owner of casinos himself. Back in Arizona Webb was a leader in building housing communities and shopping centers.

Mobster Bugsy Siegel was among the first to dream about building golf courses in the American Southwest desert.

Golf was central to Del Webb’s life; it was said to be his only hobby. His playing partners included Arizona senator Barry Goldwater, fellow casino magnate Howard Hughes, Bob Hope and Bing Crosby, who also owned a piece of a baseball team, the Pittsburgh Pirates. Webb was once quoted as saying, “Without golf it would have been difficult for me to have gotten where I am now.”

It was no surprise that Webb planned to make golf the centerpiece of the Marinette Retirement Community, the name came from a railroad ghost town that had died on the property years before. He hired a local golf professional-turned architect named Milt Coggins to lay out his first course and made sure the first nine holes would be be ready when the first buyers moved in.

And there would be buyers. By the end of the opening three-day weekend the Webb company estimated that 100,000 visitors had walked through the five model homes on display. Contracts were signed for 237 homes and the inventory of 400 planned first-year houses was gone before February. A nationwide contest was held to “Name This Active Retirement Community” and Webb liked “Sun City” the best. Four entrants had submitted that name and the Brittons from Eugene, Oregon won the drawing to receive the Meadowgrove Model 1A-R, a two-bedroom concrete bungalow valued at $8,500. If anyone doubted the importance of golf to Sun City, the first model home was at 10801 Oakmont Drive.

Living the Sun City dream.

The golf course was completed by August 1960 and Webb quickly began staging exhibitions to promote Sun City, including a series of four televised matches for professionals he called “All-Star Golf.” The player-friendly course, stuffed with dogleg holes, had more teeth than one would expect from a layout for retirees and Jerry Barber expressed surprise at the number of bunkers when he arrived for his match with Gary Player. But not too much bite - Australian Peter Thomson fired a course record 60 on his first trip around the Sun City course to beat Doug Sanders.

Most of the early play came from non-residents but by 1963 the club was reporting that “at least 25 percent of the community’s residents spend a portion of their active retirement” on golf. Sun City would soon sport five full-length courses (the original is the North Course) and three Executive-length courses. Sun City, and retirement in the United States, became synonymous with golf.

Retirement golf began to come full circle when professional golfers began to retire in golf communities. Such was the case with Nancy Lopez who was three years old when the first golf balls were hit in Sun City. She was born in California but was soon adopted by her uncle and grew up in Roswell, New Mexico. Domingo Lopez was a low-handicap golfer and encouraged Nancy to play while he tended to his auto body shop. She started playing at the age of eight, teaching herself to play by keenly watching the adults she saw at her local municipal course. When she was nine years old she just barely won a 27-hole Pee-Wee Junior tournament in nearby Alamogordo by 110 shots.

By age 11 Lopez could beat her father and the next year she won the New Mexico Women’s Amateur. At the age of 18 she finished tied for second at the U.S. Women’s Open at Atlantic City Country Club behind Sandra Palmer. Three years later when she debuted on the LPGA Tour Lopez evoked another golfing Palmer - Arnold - as she won nine tournaments, including a record five in a row to bring unprecedented excitement to the women’s game. In 1978 Lopez won Rookie of the Year, Player of the Year and Vare Trophy honors and remains the only woman golfer to hit that trifecta.

In 1997 at the age of 40 Lopez won her 48th and final LPGA title and became the first woman ever to shoot four rounds in the 60s at the U.S. Womens Open but lost to Englishwoman Alison Nicholas at Pumpkin Ridge Golf Club in Oregon. As her golfing career wound down Lopez became affiliated with the Villages northwest of Orlando, Florida, considered the largest gated community in the world with 100,000 residents over the age of 55.

Harold Gary Morse developed the Villages for his father in 1990s using Sun City as his model. Morse’s conclusion was that retirees were not so much concerned with location as lifestyle. And at the core was golf. His unique selling proposition was “Free Golf For Life” for any Villages resident. That meant unfettered access to 33 nine-hole executive courses scattered throughout the community.

There were also a dozen championship courses that could played for a nominal fee, including one designed by Arnold Palmer and another by Villages resident Nancy Lopez. The Lopez Legacy course was the Hall of Fame golfer’s first design effort and each of the three nines was named after one of her daughters. As she said, “The people that were here really kind of grew up with me.”

Doral Golf Resort - Blue Course (1962)

Start with Doris and add Albert. Blend them together and you wind up with one of the legendary names in American golf.

The ingredients for the Doral Golf Resort began forming in 1922 when Albert Kaskel left Poland for New York City where the 21-year old wound up in real estate. He eventually developed over 17,000 apartment units around the Big Apple with his company Doral Construction that wedded the first syllables of Albert and his wife’s name. They used the name for their 68-acre estate in Stamford, Connecticut and again when the couple purchased 2,400 acres of swampland hard by the Miami International Airport in 1959 for $49,000.

Kaskel turned the building of the future resort’s golf courses over to Dick Wilson, who rivaled Robert Trent Jones as the country’s top post-World War II architect. Whereas Jones specialized in building championship courses fast, Wilson agonized over the details of his design, producing a far more select output. Wilson, two years older, also believed that a golf course should look more menacing than it played, unlike his contemporary Jones who never met a birdie he liked.

Louis Sibbett Wilson grew up in Philadelphia the son of a contractor and when he was eight years old spent days carrying water to construction crews at Merion. After quarterbacking the Vermont Catamounts in college he went to work for William Flynn and Howard Toomey but did not emerge as a designer in his own right until he was in his forties after a stint in World War II building airfield camouflage. He picked up notable commissions around the country but saved his best work for Florida where he injected personality into the flatlands with curving landforms and raised greens. Wilson completed Bay Hill Club in Orlando in 1961 and the esteemed Pine Tree Golf Club in Delray Beach in 1962.

The Blue Monster at Doral is equal parts water and grass - although for many golfers it often seems like much more of the former than the latter.

To Wilson the game was all about working the ball right or left, as the course demanded. He incorporated many doglegs into his designs to reward players who could execute such shots and the Blue Course at Doral is no exception. The course immediately earned a spot on the PGA Tour and is now the third oldest course the pros play every year behind Augusta National and Colonial.

In the very first Doral Open in 1962 Billy Casper navigated cold harsh winds for four days to win in five-under par. The high scores earned the course the moniker the “Blue Monster,” which it has worn ever since. But true to Dick Wilson’s vision the course has more bark than bite for the pros. Aside from the inaugural event the tournament champion has toured the Blue Course higher than nine-under par twice in a half-century.

But the finest testament to Dick Wilson’s genius at Doral is the diversity of Doral Open champions. All-time greats Tiger Woods and Jack Nicklaus have been repeat champions. Longballers like Greg Norman, Ernie Els and Tom Weiskopf have won here. But so too have short hitters like Mike Hill and Lee Trevino. And ball strikers like Tom Kite, Jim Furyk and Nick Faldo.

Mission Hills (1967)

Augusta National has hosted more major championships than any other North American golf course. The course that has hosted the second most is at Mission Hills Country Club in Rancho Mirage, California.

Dinah Shore was an unlikely candidate to be the woman responsible for bring glamour and national television audiences to the LPGA Tour. She had been an athlete in college with the Vanderbilt Commodores but her sports were swimming and fencing. She did not play golf until she was 52 years of age after building a career as a top-charting vocalist in the Big Ban era of the 1940s and a television personality in the 1950s.

Dinah Shore did for women's golf in the 1970s what Crosby and Hope had done for the PGA Tour decades earlier.

In 1972 Shore, just four years after playing her first rounds, became the first Hollywood celebrity to attach her name her name to a professional tour event, joining the likes of Dean Martin, Danny Thomas, Sammy Davis Jr,, Jackie Gleason, Andy Williams and Glen Campbell. When first approached by David Foster, the CEO of Colgate-Palmolive to host the event she at first thought he was suggesting a tennis tournament. Foster selected a club near Shore’s home in Rancho Mirage, Mission Hills, to host the Colgate-Dinah Shore Winners Circle Tournament.

Mission Hills was at the vanguard of golf communities being built in areas of spectacular weather. Palm Springs was one such oasis, especially after 1959 passed a bill allowing the Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians to create long-term lease agreements on its land. Max Genet, Jr., a Tulsa, Oklahoma businessman, found the lure of Palm Springs so powerful that he abandoned his beloved Oklahoma Sooners and came to the desert to develop Mission Hills in 1968.

To build his first golf course Genet hired Gordon Desmond Muirhead. Like Shore, Muirhead came late to golf, an almost accidental golf course architect. He was born in Norwich, England in 1923 and like a fellow British designer Alister Mackenzie, Muirhead drew inspiration from his wartime experiences. But whereas Mackenzie sought to hide his course features from a background in camouflage, Muirhead had been an RAF navigator with over 2,000 mission hours and looked at his golf courses from a more lofty perspective, He loved downhill holes and the power it afforded golfers standing on the tee.

Muirhead worked as a land planner and only came to golf in the 1960s whens course began to be integrated into residential communities like Mission Hills. Despite his growing notoriety as an architect, Muirhead was a high handicapper and seldom visited a course with a golf bag in tow. He enjoyed the “community” designing as much as the “course” designing and when Muirhead teamed up to create Muirfield Village in Dublin, Ohio with Jack Nicklaus he was proud not only of his work on the wisely praised course but the “village” part of Muirfield Village as well.

Muirhead would sour on golf completely in the mid-1970s and light out for Australia where he bought an art gallery and toiled on large-scale community projects. When he came back to golf after a dozen years the artist in his soul was unleashed. Muirhead began using golf courses as roiling canvases, infusing his designs with symbolic and spiritual references. A Desmond Muirhead course was best viewed from a bomber’s seat at 10,000 feet.

At Stone Harbor Country Club, where each hole was named from a incident in Greek mythology, the seventh hole featured a football-shaped island green framed by bunkers in the form of menacing pincher-like teeth. The ninth green at Stone Harbor was shaped like the state of New Jersey. Muirhead designed bunkers that resembled Nordic crosses. At Aberdeen Golf and Country Club in Boynton Beach, Florida the entire 11th hole depicts a mermaid slinking in the water complete with a fan-tail tee box and “earthen scales” lining the fairway.

The golf world was alternately mystified, amused and disdainful of this later period of Muirhead’s work. He was lauded more in the design world where artistic statements were more celebrated than shot values. And that no doubt pleased Desmond Muirhead who never bothered to join the American Society of Golf Course Architects.

Colgate-Palmolive and Dinah Shore instantly raised the profile of women’s golf in 1972. The tournament offered a $110,000 purse - the first time women had ever played for money in the six figures. Jane Blalock won with a three-under par total of 213 and took home a $20,050 check when the average first place prize was $4,600. Beginning in 1983, the tournament, then sponsored by Nabisco, became an official women’s major, the LPGA’s version of the Masters.

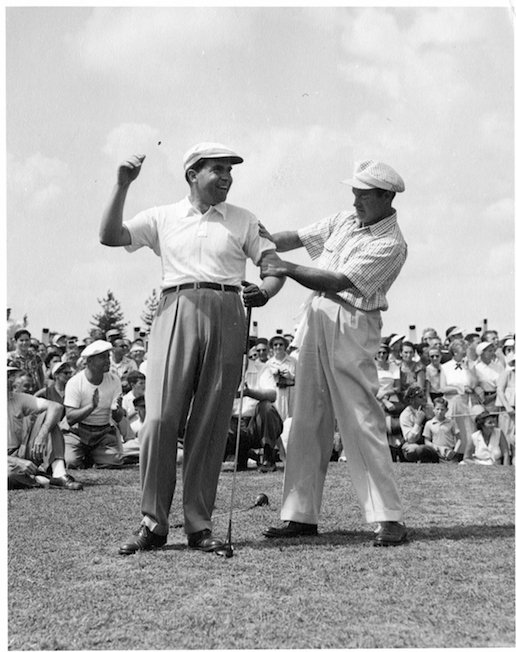

Hijinks were always afoot at celebrity pro-ams - Bob Hope could even turn Richard Nixon jolly.

Television did not locate women’s golf until 1963 when the final round of the U.S. Women’s Open was aired from Kenwood Country Club in Cincinnati, Ohio. The “Dinah Shore” as it was known on Tour, changed that. And Desmond Muirhead had designed a television star with his closing hole, a par-five that flows downhill - naturally - to an island green. In 2009 Brittany Lincicome became the first player in golf history to win a major tournament on the final hole with an eagle at the 18th.

In 1988, overcome with exuberance after setting the tournament record with a 274 to win her second Dinah Shore championship, leaped with her caddie Bill Kume into the pond surrounding the green. Alcott won a third time and reprised her splashdown, taking Dinah withe her. After Donna Andrews took the plunge in 1994 the celebratory leap became a mandatory tradition. The splash zone is now named Poppie’s Pond, a name his grandchildren called long-time tournament director - and the man who gave Dinah Shore emergency golf lessons in preparation for the first pro-am - Terry Wilcox.

Dinah Shore’s name was hauled down off the marquee in 2000, six years after he death. But her presence is not forgotten. When the Dinah Shore Wall of Champions was dedicated behind the first tee of the Dinah Shore Tournament Course show biz and golf luminaries were out in force for the dedication, including Mickey Wright who rarely showed up for golf-related functions following her retirement after the 82nd and final LPGA win in the 1973 Dinah Shore. All agree that no one had ever done more for women’s professional golf than the lady who once thought she was hosting a tennis tournament.

Harbour Town Golf Links (1969)

Jack Nicklaus? Charles Fraser had heard of him. But this other guy, what’s his name, Pete Dye? Who was he?

Charles Elbert Fraser was born on June 13, 1929 into a career military family. His father, Joseph B. Fraser served in both world wars and the Korean War and rose to the rank of general. He commanded the South Carolina National guard and also dabbled in the timber business. In the 1940s General Fraser and two partners bought one of the largest islands off the Atlantic coast, named for a 17th century British sea captain named William Hilton.

In the 1950s Charles Fraser began eyeing his fathers land with more than two-by-fours and shingles in mind. He convinced his father to sell him a chunk of the southern part of Hilton Head Island. Fraser had gone to Yale Law School and knew his way around a property deed and protective covenants. He envisioned a new type of southern resort community, one with ecologically sympathetic multi-million dollar houses instead of beach cottages, gated subdivisions and nature preserves. No structure would be taller than the tallest tree and all buildings would be painted in natural earth tones. Oh, and there would be golf courses.

Charles Fraser made Hilton Head, one of America's largest coastal islands, a haven for golfers.

George Cobb designed the first two golf courses for Sea Pines Plantation and had drawn up plans for the third in 1967 when Nicklaus, eager to get into the golf course construction business, approached Fraser about designing the course. It was intriguing to have the best player in the game on board but also would be a risky play to trust the marquee course of his 5,000-acre development to a designer with zero experience. Fraser also had promised the PGA a tournament course for 1968. Nicklaus mentioned that he intended to collaborate with an insurance broker-turned golf course architect from Indiana named Pete Dye.

Paul B. “Pete” Dye had spent part of his hitch in the United States Army Airborne during World War II as the greenskeeper for the Fort Bragg golf course in North Carolina which gave him plenty of time to play at Pinehurst and get acquainted with Donald Ross. After the war he played amateur golf well enough to qualify for the U.S. Open at Inverness in Toledo in 1957 and become the youngest member of the Connecticut Mutual Life Insurance million-dollar roundtable. And Dye was maybe not even the best golfer or insurance salesman in the family - His wife Alice was the youngest member of the quarter-million dollar roundtable and collected nine Indiana state amateur titles.

Pete and Alice undertook their first design job at a nine-hole course in Indianapolis in 1959, doing the work at El Dorado Golf Club for free. Paid assignments followed and at the aged of 36 in 1961 Dye traded insurance for golf design. Like the famous architects of a half-century before Pet and Alice traveled to Scotland to study the classic seaside links. His first acclaimed work was at Crooked Stick Golf Club in Carmel, Indiana in 1964 that John Daly would conquer to win the 1991 PGA Championship. When he started work on The Golf Club near Columbus, Ohio Dye called up hometown hero Nicklaus for advice.

Fraser gave Nicklaus and Dye the job, got a one-year extension from the PGA and got out of the way. Dye immediately showed he planned something unconventional for Harbour town. He took Cobb’s routing and jettisoned the 18th hole that worked back to the clubhouse and put it along the Calibogue Sound marshes. Fraser jumped on board and built a red-and-white banded lighthouse as a beacon for the harbor and a backdrop for Dye’s hole. Golf had its most famous finishing hole east of Pebble Beach.

Nicklaus threw himself into the project, visiting the Hilton Head site 23 times in 11 months as Dye set about introducing new words into the golf vocabulary: railroad ties, pot bunkers, waste areas, Pampas grass. In an era when golf - personified by Nicklaus - was about power, Harbor Town featured the smallest greens on tour. From the tips the course did not play 7,000 yards.

There was grumbling when the pros saw Harbour Town for the first time at the heritage Classic in 1969. But any chance for rebellion was quashed when Arnold Palmer came home the winner and called Nicklaus and Dye’s creation a “thinking man’s course.”

But it would not be correct to attribute this modern classic solely to Jack Nicklaus and Pete Dye. The drive-and pitch 13th, one of the most memorable holes at Harbour Town, was the handiwork of Alice Dye, who sketched it out on a cocktail napkin just as her husband was wont to do.