BASEBALL IN DELAWARE

THE TOWN BALL ERA

Early Delaware baseball matched local teams. Here was a chance to offer prideful tradesmen, for instance, a chance to meet on level ground. When groups of butchers squared off it was the “Cows” and the “Steers.” There is an early account in Delaware of “a match game of baseball played between the painters and printers for a keg of beer. The printers beat, but the painters refused to pay.” Another popular match-up was teams of single men against nines of marrieds.

These new games of baseball were often arranged for charity. In one novel game a “fat” nine of Wilmingtonians totaling 2300 pounds engaged a “lean” nine of but 1125 pounds. The admission fee of 25 cents was given to the House For Friendless Children. The big men took the first game but the “leans” exacted a 51-22 revenge in the next game after “the heavy men came on the grounds not only fat, but saucy, and pranced around in gay ribbons, smiling broad smiles at the recollection of their former victory.” The two games raised $51.25.

Baseball, in all its various forms, swept the country rapidly. In 1866 it was observed that “the game of baseball has now become beyond question the leading feature in the outdoor sports of the United States.” Inevitably towns began presenting their best players against those from the village down the road.

The first teams in Delaware were the Lenapis of New Castle and the Atlas Club of Delaware City, the latter being a family affair featuring three Reybolds and two Prices. Games were arranged by letter, often printed in the local papers. When a challenge was accepted the game would be played according to the regulations adopted in New York in 1865 by the National Association of Baseball Players. Most important was the selection of an umpire through negotiation. The team first up was decided by a coin toss.

The games were heavily bet on and the atmosphere was often less than gentlemanly. A good match could be expected to draw 500 or more fans. The game was rough, both on the field and off. At one game it was reported, “that some man, whose mind was more thoroughly imbued with the love of money-getting than with common sense or decency, had set up a stand for the sale of beer in the judge’s stand, and some boys and young men having drunk too much, commenced a fight. This drew all the spectators from the game and stopped the play for a short time.”

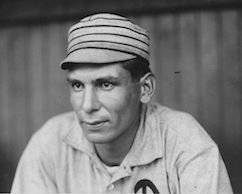

The Wilmington Chicks.

By the 1870s baseball clubs were organized throughout Delaware, including several black nines: the Flat Foots of Georgetown, the Long Nine of Bridgeville, the Independent Baseball Club and the Hercules team. The best ball was played in Wilmington and it was no trifling matter. From the local Wilmington paper came this report: “The Academic Baseball Club of Milford, so badly beaten by our city clubs while on a visit here recently, make all sorts of excuses for their defeats but the local paper of the town tells the club the best and most truthful excuse is, ‘they could not play well enough.’ Correct.”

While professional baseball was at best a spotty proposition in Delaware throughout the nineteenth century, amateur ball at the town level remained popular, especially in the rural environs. Junior teams were formed for boys and challenges were accepted in the same manner as their adult counterparts. As a result baseball games could be found in every town in the state on any Saturday well into the 1900s.

THE DIAMOND STATE BASEBALL CLUB

In 1865 a group of young businessmen gathered in a broker’s office at the corner of Fifth and Market in Wilmington and excitedly discussed the formation of a team to play this new game that was sweeping the country. The Diamond State Baseball Club was born.

Early in May of 1866 the young men, resplendent in their new suits of black and white checkered shirts, black pantaloons and blue skull caps, marched proudly through the streets of town to the baseball grounds at Delaware and Adams for their first game with the powerful Athletics of Philadelphia. It would be charitable with too much credit to term the contest a “battle.”

The Athletics were acknowledged as the champion nine of the country and were too much a team for their novice opponents. Home runs over the fence were the rule rather than the exception. One Diamond State fielder so wearied of jumping over the outfield fence after baseballs that he stationed himself out of the field of play. After awhile the home team placed all of their club in the field. Even with 20 or 25 players scattered about the lot the Delawareans had difficulty in holding down their formidable foe.

The crowd for the novel event, however, was hardly dissuaded by the lopsided goings-on and when deliberate Philadelphia errors enabled a Diamond State player to circle the bases with the first Wilmington run the fans went wild with delight. The final score was Athletics 104, Diamond State 5. Undeterred, the vanquished Delaware team feted their visitors in grand style that evening at a local hotel.

Weeks of hard practice followed and the Diamond State club deemed itself ready to challenge the more established Lenapis of New Castle to a series for the state championship. Playing on their home grounds the New Castle ball tossers won the first game handily by 10 runs. The rematch in Wilmington looked much the same until Diamond State exploded for nine runs in the final inning to prevail 35-32. They banqueted their defeated opponents and sent them home with three hearty cheers.

Buoyed by their spectacular come-from-behind first victory the Diamond Staters swept over the Lenapis 30-7 in the deciding tussle. By this time the Wilmingtonians had lured into the fold, “Fergy” Malone, who would later become the greatest pitcher of his day. Although no players were paid at the time, not even expenses, Malone was assisted in setting up a cigar store at Seventh and King Streets for his diamond exploits. Malone was worth the investment; he never lost while in the box for the Diamond State Baseball Club.

The Wilmington team took a boat to Delaware City and beat the Atlas Club resoundingly 32-15 to clinch the state championship before a large turnout of partisan supporters. Diamond State did not have long to enjoy their laurels in peace. Another Wilmington team, the Wawasets, organized and were as strong as any Diamond State had yet met in Delaware.

The two nines met often over the next few seasons. For most of that time Diamond State, especially with Malone handling the pitching chores, was clearly superior. But against other pitchers Wawaset was able to win its share of games as well. The Diamond State Club was able to retain its mythical state championship until it disbanded in the early 1870s.

THE QUICKSTEPS

With the dissolving of the Diamond State Baseball Club in the early 1870s there was no acknowledged champion baseball nine in Delaware. After a couple important wins in 1872 the Quicksteps were quick indeed to claim the mantle but they still had much to prove on the field. Late in 1872 the Quicksteps fell to Wilmington’s Eckford nine before an overflow crowd at the diamond at Delaware and Adams streets.

In 1873 the Actives of Wilmington were the leading team as the Quicksteps did not reorganize until July. The new Quicksteps within a short time became the strongest baseball club to yet represent Wilmington. With star pitcher Frank B., better known as “Flip,” Lafferty in the box, this club never suffered a defeat at the hands of a local club. In the summer the Quicksteps travelled to southern Delaware dispatching nines from Milford and Georgetown and declaring themselves “Champions of the Peninsula.”

By 1874 the Quicksteps were firmly established as “Delaware’s team.” The celebrated nine was by now combatting mostly out-of-state teams and their exploits were assiduously detailed on the front pages of the Wilmington papers. They held their own in games against Philadelphia clubs and crowds of 500 fans were common at their afternoon games at Scheutzen Park.

In 1875 the Quicksteps joined the national Amateur Association, playing games against professional and amateur teams. The resourceful nine displayed an uncanny knack at tallying in the late frames to win games on their field out by the 3rd Street Bridge. On July 15 the Wilmington Maple Leaf engaged the Quicksteps for the state championship. There was considerable wagering on the game with the Quicksteps only slight favorites as the Leaf featured two players from powerful Philadelphia teams. The Quicksteps at first refused to contest against a non-Wilmington team but finally agreed to play and jumped to a 11-1 lead after two innings. The Quicksteps thumped the Maple Leaf 24-4 for the state title.

On August 7 the Quicksteps played their first game against a professional nine, the Chicago Whitestocking. The contest got off to a less than auspicious beginning. According to game accounts, “The first batter knocked the first ball pitched to him to right field and made second. The ball fell on the track and rolled under a horse’s feet, and while Stock was getting it the horse lifted his hind foot and made an ugly wound on the player’s face, necessitating the stoppage of the game for some time and the substitution of Kelley for Stock.” The Quicksteps slipped behind 5-0 after two innings and fell 11-4 but the Chicago manager praised the nine as one of the finest his team had yet met.

The Quicksteps again marched through the south crushing Milford 27-5 and demoralizing Dover 29-0. Before the Smyrna game their arrival was thus heralded in the local paper: “The Quicksteps came to town last night and will beat the club of this place this afternoon.” They did, 29-1. In the sixth inning, when Lafferty was “pitching most wickedly,” one of the prettiest girls present, after consulting a dozen of her companions, pencilled the following note and had it sent to him - “Dear Frank: Please let our boys have one run; just one. Affectionately yours, the ladies of Smyrna.”

Upon receipt of the plaintive missive Lafferty bore down even harder and the ladies appealed to other Quickstep players. After the letter was printed in the Wilmington paper rooters took up the refrain against futile visiting teams. The Quicksteps built new grounds and forbade betting. They pummeled the reorganized Diamond State club 26-4 and even beat the fabled Philadelphia Athletic 6-4. The Quicksteps were now playing to great fanfare and 50 fans followed the team to Reading on an excursion train. The Wilmington team lost to the Reading Active before a record crowd of 1800. The Quicksteps complained of shabby treatment by the Reading fans and when they won the rematch 16-7 in Wilmington a bitter rivalry was hatched.

The rubber game was arranged in Philadelphia to accommodate the large followings of each team. Each side put up $100 with the winner taking all. The Quicksteps led 6-2 into the 8th inning but then surrendered 12 runs, playing so poorly there was talk the game had been sold. The jubilant Reading nine returned home to a full parade.

Meet the most celebrated Delaware nine of the 19th century: the Quicksteps.

The games had been so entertaining no time was wasted setting up another three-game match. By this time Reading had notched wins against teams from Philadelphia and New York and were boasting that they were the best amateur team in the country. The first game in Reading spilled over to 10 innings before the Active prevailed 9-8. The match was acknowledged as “the finest game yet played in Reading” and was so popular an exhibition was scheduled after the Quicksteps returned from a trip to Harrisburg. Wilmington won the “practice” game 8-6. Back in Wilmington the series resumed with the Active winning 14-8 and then sweeping the series by thrashing the Quicksteps 16-3 in Reading.

The Quickstep players got no money for their exertions and a large benefit was held to defray expenses. Late in October an eighth meeting was arranged between the Active and the Quicksteps in Reading. The contest degenerated into a mob scene forcing the Quickstep team to flee from the field. The Active had set up the game only as revenge for what they considered shabby treatment for the last game in Wilmington when the Quicksteps delayed the start of the game causing Reading to miss the last train home and incur extra expenses. In retribution Reading turned over only $25 of a $60 guarantee. The great rivalry ended in festering bad blood.

In the Centennial year of 1876 the Quickstep Association formed a stock company and joined the professional National Professional Association. Al Hindle of the Quicksteps was selected president of the league featuring teams from Philadelphia, Reading, St. Louis, New Haven and Brooklyn. The team was stocked with players brought in from out of town and paid about $10 a week to play ball in Wilmington. The new team donned snappy new white uniforms with blue stockings, red belt, blue trimming and white shoes. “Quickstep” was emblazoned across the breast.

Delaware’s first professional team won laurels on the field but only a modest following among Wilmingtonians. Meanwhile the former Quicksteps reorganized to form the Quickstep Amateurs. Evans and Lafferty, spirited away from the professionals, were key pitchers on one of the strongest amateur nines in the country. The team opened with a 24-3 trouncing of the Philadelphia Keystones on the new grounds by Pennsylvania and Delaware avenues before a sellout crowd.

Wilmingtonians were regaled with success stories from both Quickstep teams in the daily papers. Inevitably a 7-game series was arranged between the amateurs and professionals. More than 1200 fans packed the grounds for the opening match. Admirers cheered lustily for play on both sides but animosity ran deep between the players. The game was delayed by lengthy rules debates and cries of “pack up the bats and go home” emanated from both sides. The professional nine eventually prevailed 11-6 but the proceedings of the play sent the remaining fans away with diminishing enthusiasm.

The two teams split the next two games but the series dissolved before the result of the fourth game was announced. The decline of baseball in Wilmington had begun. The professional team could not muster enough support to survive the season and the Quickstep Amateurs returned from a western road trip without the services of Lafferty, Evans, Splaine and Smiley, who were all raided by other clubs. In August the manager Manuel Richenberger, who had been the first to enclose a baseball park in Delaware, was ousted and the team reorganized but the glory days of the Quicksteps were over.

In 1877 the Quickstep amateurs were salaried and by mid-season were acclaimed as one of the strongest teams in the country. White flags flew on street cars on game days and monthly tickets were sold for $1 but, while Wilmingtonians were still greatly interested in baseball, they weren’t interested in paying for it. A typical Quickstep game would draw about 500 paying customers but twice that would gather on the hills, rooftops and wagons around the park. Wilmington papers implored the fans to watch “from inside the enclosure” and support the team to keep it but the death knell was sounded.

The Quicksteps disbanded before the 1877 season wound down and in the spring of 1878, while amateur games proliferated around the state, there was no top flight competition. The Quicksteps were not revived until July 28 at Eighth and Broom Streets but the effort failed. Delaware’s nationally recognized amateur nine was no more.

DOVER BASEBALL

No town loved its baseball more than Dover. It was universally conceded that the grounds of the Dover club were the finest in the state but the best ball played there was seldom by the Dover nine. In 1874 Dover hosted the Kent County championship but was routed by Smyrna and had to watch Milford and Smyrna battle for the title on their home turf.

It was recorded that the Milford win, “notwithstanding the rays of old Sol which were exceedingly scorching, was witnessed by quite a large number of persons, including a small sprinkling of ladies, who seem to take as much interest in the exercises of bat and ball as the sterner sex.”

On June 25, 1875 the first professional game in Delaware was arranged in Dover between the Athletic of Philadelphia and the New Haven of Connecticut. An extra 1500 temporary seats were erected for people “regardless of race, color or previous condition or servitude.” Anxious spectators began coming to the town at 10:00 a.m. but it was not until the 2:00 p.m. train arrived that the stands for the 3:20 game filled.

An umpire’s mistake in the top of the first inning completely snuffed out a New Haven rally and the team seemed not to recover. Philadelphia, led by the great Cap Anson, scored in each of the first three innings and cruised to a 12-1 win.

Cap Anson was the first Hall-of-Famer to play on Delaware diamonds. Unfortunately for Dover he was wearing a Philadelphia uniform at the time.

1875 was a better year for the local nine who distinguished themselves against downstate foes. A visit by the Quicksteps was much anticipated by the Dover faithful; a victory could bolster a claim as state champion. But the game was a fiasco. After four innings the contest was mercifully stopped with the home team trailing 29-0. The Dover nine would never quite meet the expectations of the devoted townsfolk.

THE AMATEUR LEAGUES OF DELAWARE

In the 1880s Seaford emerged as the leading baseball town in downstate Delaware. In 1888, having not lost a game in three years, the Seaford nine dumped the Delaware Field Club 9-3 and claimed the mythical state baseball championship.

The boastings from down the peninsula did not escape the attention of Wilmington baseball men who instigated the formation of the Amateur Baseball League of Delaware to decide the best baseball team in the state. The league included Seaford and three Wilmington nines: Americus, Wilmington and the Quicksteps. All players were required to be amateurs and residents of the city represented.

The league got off to a rousing start in attendance; the “bleaching boards” were always full and games elicited much spirited betting. More than 1000 people stormed the grounds for the much awaited home opener at Seaford which prompted the observation that “one commendable feature of baseball attendance in this town (Seaford) is the presence of hundreds of ladies at each game. Their presence serves to eliminate the too-prevalent objectionable features at baseball matches and at the same time stimulates the players to exert themselves.”

Seaford was less successful on the field, however, as they struggled to an 0-4 start. Americus was far the strongest team in Delaware, winning their first four matches by a combined 49-10 score. When Americus traveled to Seaford, however, they were dispatched 6-0. Immediately there were protests that Seaford had used a professional pitcher and catcher from Baltimore to dominate the game. Wilmington papers termed the local umpiring “criminal.”

With new pitcher “Davis,” Seaford reeled off two more wins and during a tumultuous league meeting on August 2 all the clubs conceded to using pros except Americus. Manager Ross of Seaford admitted that he could not compete with the Wilmington club on local talent alone. And no wonder; consider the distribution of population in Delaware in the 1880s - Wilmington, 60,000; Dover, 4,000; New Castle, 4,000; Smyrna, 2,500; Milford, 2,000; Seaford, 2,000; and Newark, 1,000. Seaford resigned from the association and the Amateur Baseball League of Delaware fizzled.

The next year another attempt was made to organize the state teams. Dover, Wilmington, Smyrna, Camden and Milford banded together to form the Delaware State League. This time each team was allowed to hire eight players and there were no residency requirements. But even before the league could get underway there was controversy over Dover’s use of second baseman Bill Higgins, a Wilmington player who had played 14 games for the Boston Braves the year before. The Smyrna management claimed they had signed Higgins and Dover threatened to pull out before the matter was resolved in their favor.

There were 600 on hand to see Dover nip Wilmington in the League opener and play was combative from the start. Dover led the list with a 5-2 mark with Wilmington a half-game back at 4-2, with both losses to Dover. Dover travelled to Wilmington to administer a third defeat to the big city but the league was beginning to break up for want of downstate attendance. Smyrna couldn’t compete with the other clubs in salaries for players and dropped out and within two weeks there was no more tournament for baseball supremacy of Delaware.

MINOR LEAGUE BASEBALL - THE INTERSTATE ASSOCIATION (1883)

After several years in a Rip Van Winkle state professional baseball re-awakened in Wilmington in 1883 when a city team joined the Interstate Association, banding together with nines from Pottsville, Reading, Brooklyn, Trenton and Harrisburg. Delaware fans could expect a game nearly every day and the Union Street grounds were the best in the Association behind the Brooklyn Park.

Brooklyn wound up being the class of the short-lived Interstate Association - not Wilmington.

The new Wilmingtons adopted the storied name “Quicksteps” and proudly posed for pictures in their new white flannel uniforms with blue stockings and belt and blue and white caps. Early play was uneven but the team consistently drew between 500 and 800 fans to the park. By July, however, the Quicksteps had slipped to 11-19 and stirred the wrath of the local press: “The players still have the consolation left that they can continue with their poor exhibitions of baseball until the end of the season without losing their present standing.”

By August wins were so rare the team returned from a win on the road to the headline: THE QUICKSTEP ACTUALLY WINS A GAME. Their first win in over two weeks was witnessed at Union Street by scarcely 200 people. The team management couldn’t conquer the problems on the field or off. The season was peppered with managerial and roster changes, all to little effect.

As to the fans, it was reported, “quite as many persons witness the game from neighboring trees and buildings as pay their way to the park. An enterprising individual with an old barn and rickety house back of the yard sells privileges to occupy positions where the game can be seen a square away. These spectators are, in the majority, able to pay admission to the grounds, but would rather get an indifferent view of the field at half price. These patrons do more growling at the Quickstep club than all the paying ones together.”

The Quicksteps stumbled to a 29-49 finish in what was left of the Interstate Association. Still the team was considered a strong franchise, plagued mainly by mismanagement. Backers easily sold $2000 worth of stock for a new team in 1884.

MINOR LEAGUE BASEBALL - THE EASTERN LEAGUE (1884-85)

Despite the dismal minor league experience of 1883 Wilmington entered the Eastern League, one of the four leading professional organizations along with the National League, American Association and Northwestern League, in 1884. Manager Joseph Simmons recruited an especially powerful team, fortified by strong batters, and the Wilmington nine was favored for the title in preseason opinions around the league.

Matched with Allentown, Newark, Richmond, Harrisburg, Baltimore, Reading and Trenton the Wilmingtons - sporting no nickname - were the scourge of the circuit from Opening Day on May 1. They won ten of their first eleven games by the scores of 21-6, 11-1, 15-8, 13-1, 7-8, 13-4, 10-2, 20-5, 10-3, 7-6 and 21-6. Lefthander Daniel Casey and righty Edward Sylvester “The Only” Nolan were phenomenal pitchers who dominated the league with 10 and 19 wins respectively.

Only Trenton offered much of a challenge but the New Jersey men were beaten 12-10 before 1300 Wilmington fans. It was the high point of the season. The lopsided games held as little appeal to Delaware fans as the previous years’ hapless losers. Nineteen straight wins pushed the record through 50 games to 40-10, with the team averaging more than 10 runs a game.

Shortstop Thomas “Oyster” Burns led the Wilmington attack with an astounding 12 home runs. Burns got his nickname from his off-season job of selling shellfish; he was known around the league for “an irritating voice and personality.”

19-year old Oyster Burns led the champion Wilmington nine at the plate in 1884 before embarking on an 11-year major league career.

The pennant chase was over by August. Wilmington stood 46-12. The owners, battling red ink at the gate all season, closed the team down as soon as they had mathematically eliminated all challengers for the championship. It was hardly a triumph draped in glory.

In the ultimate triumph of hope over experience Wilmington once again joined the Eastern League in 1885. This time, with little money to pay players, they were routed early, although barely 100 fans were turning out to witness the slaughter. After a 1-14 start the team relocated to Atlantic City verifying the conclusion reached during the championship 1884 season - Wilmington would not support a team. The third successive attempt to run a baseball club in the city had come to grief before the season was over.

DELAWARE IN THE MAJOR LEAGUES

“The papers have all been signed and Wilmington’s pet club, which had won recognition as the champion of the Eastern League, is ready to worry the nines of the Union Association all the way from Boston to Kansas City,” trumpeted the Every Evening on August 18, 1884. And so began Wilmington’s hopeful odyssey into major league baseball.

The Wilmington Quicksteps had laid waste to the Eastern League in 1884 winning 51 of 63 games by the middle of August. They had already clinched the pennant when the owners jumped to the Union Association to replace the failed Philadelphia Keystones. The Union Association was in its first - and only - year as a third major league, formed in opposition to the reserve rule that governed the rival National League and American Association.

Fans in Wilmington were ready for the challenge because, as Every Evening went on to report, “experience has demonstrated that, though many of the matches with Eastern League clubs were enjoyable and hard fought contests, the almost continuous line of victories for the home club seemed to have impressed the admirers of the game with the foregone conclusion as to the result, and to have lessened the attendance so much that the club’s existence, for financial reasons, was beginning to look doubtful.”

The Quicksteps traveled to Washington where they won their first Union Association game against the Nationals before 1800 fans at Capitol Park, plating two runs in the 8th inning to prevail 4-3. The Washington manager praised the Quicksteps as “a fine set of ball players who gave a beautiful display of fielding and won favor for their quiet, gentlemanly deportment.”

Wilmington fell the next day to the Nationals 4-2 but more importantly lost their shortstop and centerfielder who jumped to the Baltimore club. The hastily reassembled Wilmington nine was drubbed 12-1 in the third game of the series, getting no hits and striking out 13 times. Washington administered decisive 14-0 and 10-4 defeats in the last two games, the four runs coming meaninglessly in the ninth inning.

The roster was still fluid. Outfielder Dennis Casey, hero of the opening day win but ineffective in the four-game losing streak, was released, but not for his play. “Dennis Casey’s behavior has been despicable and contemptible,” it was reported, “and considering also his unpopularity with the rest of the nine, it is well that he has left.”

Rookie southpaw Dan Casey won Wilmington’s first major league game. After the club disbanded he went on to win 96 major league games.

Wilmington departed Washington for a series in Boston, but arrived late and had to forfeit the first game 9-0. It was supposed that some of the team members had stopped too long in New York City and misunderstood the directions to the Boston park when finally arriving in the Hub. The next day the Quicksteps outhit the Bostons 7-6 but lost the game 7-1 under the burden of 23 errors.

Hope emerged the following day when Wilmington jumped to a 4-0 lead after two innings but the advantage could not be sustained. Blame for the 5-4 loss was laid squarely on catcher Tom Lynch: “Lynch’s bad catching lost the game here yesterday, as all other games have been lost by poor playing in this position.”

After a respite by rain the Quicksteps were once again shut down 3-0, dropping their record to 1-8. The team finally returned home for their first games at the field at Front & Union dragging an eight-game losing skein. 600 fans turned out for the game with Cincinnati and were rewarded with the second Quickstep Union Association win. The colorfully named The Only Nolan twirled a 3-2 masterpiece, felling 11 Queen City batters with his deceptive curve. Local fans could also revel in the work of native Wilmingtonian George Fisher at shortstop.

The next day the Quicksteps enjoyed a 3-1 lead into the 6th when pitcher John Murphy was struck a “terrible blow” with a pitched ball while at bat. He remained in the game but his effectiveness ebbed and Cincinnati came back for a 7-3 win. After the game Wilmington lost John Cullen, a stalwart in the middle of the order, when he fell down an elevator well. Cullen promptly retired to his native California to edit a local newspaper.

Next in town for the Quicksteps was the powerful St. Louis team that was dominating the league on their way to a 94-19 record. Nolan, the team’s highest paid player at $325 a month, held the talented visitors in check but fell 4-2. The succeeding games were perfunctory losses; 9-3, 11-3 and 7-1. A soggy 4-3 loss to Baltimore dropped the Quicksteps to 2-16.

Ed “The Only” Nolan, a 27-year old Canadian pitcher, was the Quicksteps top-paid player. Seven years earlier while pitching in the minor leagues for Indianapolis Nolan threw 76 complete games, won 64 and pitched 30 shutouts - all records in professional ball.

On September 15 Kansas City and Wilmington assembled for a game but gate receipts totalled only $40. The visiting team was guaranteed $75 and the Quickstep stockholders were unwilling to go deeper into their pockets to make up the balance. The game was cancelled and the team folded.

Milwaukee played out the final 12 games of the season and the Union Association was gone too. Although Wilmington’s adventure in big league baseball was a brief one their 2-16 final log stands as the worst team mark in major league baseball history.

MIGHTY CASEY FIRST STRUCK OUT IN DELAWARE

For the better part of 50 years a trolley conductor in Binghamton, New York entertained riders with a tall tale - he was the inspiration for Ernest Thayer’s celebrated baseball poem “Casey At The Bat.”

The story Dan Casey told was this: “I was a left-handed pitcher for the Phillies. We were playing the Giants in the old Philadelphia ballpark on August 21, 1887. Tim Keefe was pitching against me and he had a lot of stuff, but I was no slowpoke myself. It was the last of the ninth and New York was leading 4 to 3. Two men were out, and there were runners on second and third. A week before, I had busted up a game with a lucky homer and folks thought I could repeat. The count went to 3 and 2 and he burned one over the plate. What a miss it was.” Casey claimed that after that game Thayer, a Philadelphia sportswriter, showed him a poem he had scribbled about the incident.

The next year Thayer was in San Francisco and “Casey at the Bat” became a popular theatrical recitation. The travails of the Mudville nine soon became ingrained in American lore.

Was this Wilmington’s Dan Casey?

In the 1930s as baseball was organizingthe Hall of Fame in bucolic Cooperstown, New York the lords of the game went all in on the Abner Doubleday myth of the game’s creation. When they heard of Casey’s story down the road in Binghamton archives were checked and most of the baseball part of the story rang true.

Even though Thayer always maintained that Casey was a fictional creation, baseball embraced the real-life Dan Casey version. He was an unlikely “mighty” Casey. Primarily a pitcher, that lucky home run was his only one in 710 career at bats. His lifetime batting average was an unfrightening .162.

Nonetheless, Time magazine ran an article on the “Mudville Man.” At the Hall of Fame grand opening festivities in 1939 Casey was interviewed on a national radio show and presented with a lifetime pass to all the ballparks in the land. Seventy-six years old at the time, he re-created his epic failureon the field of an exhibition game.

If Dan Casey was indeed the original mighty slugger of legend his first failures were with Wilmington in the Eastern League in 1884, when he signed his first professional contract as a 21-year old off the family farm just outside of Binghamton. He died in 1943 at the age of 80, going to grave convinced he was “the mighty Casey.”

MINOR LEAGUE BASEBALL - THE MIDDLE STATES LEAGUE (1889)

In August of 1889 Wilmington baseball enthusiasts staged two exhibitions to gauge local support for a professional baseball team. Turnout was sufficiently encouraging to convince the investors to enter the crumbling Middle States League with teams mostly from central Pennsylvania.

The new team, adorned smartly in gray suits with maroon trim, actually beat the powerful Cuban Giants (48-17), a collection of professional black players from Newark who were an attractive draw wherever they went. The Giants rebounded to drub the Wilmingtons several times to drop the home team to 4-9.

Once again Wilmington would not last to the end of a minor league campaign, but this time the apathy of Delaware fans could not be blamed. In mid-September the worst storm in 50 years lashed theEast Coast, devastating many areas in the region. Rather than re-start the schedule with only a handful of games the backers closed operations for the 1889 season, promising to return in 1890.

MINOR LEAGUE BASEBALL - THE ATLANTIC ASSOCIATION (1890)

Enthusiasm was never higher in Wilmington for a minor league season than for the upcoming Atlantic Association season in 1890. A new ball park was readied at 29th and Market Streets and Governor Benjamin T. Biggs was on hand to throw the first ball into play. The crowd was estimated at 2500 but paid attendance was only 1484. The rest jumped the fence and easily eluded the six overmatched policeman on duty. Once again Wilmingtonians had demonstrated their desire for baseball and their unwillingness to pay for it.

By the third game the team was 0-3 and attendance had plummeted to 300. Joseph Simmons, who had managed the now revered 1884 Quicksteps, was brought in to lead the squad and guaranteed he was not going to finish as the Atlantic Association tailender.

The record deteriorated to 4-31 but the assemblage was still considered a good one. The Wilmingtons pulled together for four straight wins and actually reached 28-50 when local legend Simmons was released. Only mildly despondent, he put together a pro team to tour the peninsula and give Delaware towns a chance to try their hand against professional talent.

Late in the year Wilmington traveled to Baltimore to meet the league-leading Orioles and could muster only 7 players; two more were recruited from the lot at the ballyard. Soon after they were expelled from the league for non-payment of dues. Once again Wilmington did not last a full season in the minor leagues.

MINOR LEAGUE BASEBALL - THE ATLANTIC LEAGUE (1896)

After a lull of several years baseball fever once again gripped Delaware in the mid-1890s. The smaller towns fielded teams featuring pro players and strong Wilmington amateur teams like the YMCA and Rockford began attracting great crowds. Thus inspired, Wilmington once again entered the minor leagues, this time joining Newark, Hartford, Paterson, New Haven and the New York Metropolitans in the Atlantic League.

It seemed a strange geographical choice for Wilmington, the only non-New York area team in the circuit. But the Atlantic League was the strongest league Wilmington had yet engaged. All the teams were competitive on the field and each was well supported among the local enthusiasts.

In Wilmington the Union Streets grounds were fixed up handsomely. Padded seats were installed on the players’ benches and the grandstand for the fans was spruced up considerably. Smoking was prohibited in the south stands which were reserved for ladies and their escorts. Outside the park accommodations were provided for 3000 bikes. Save the early Polo Grounds, where the Metropolitans played, the Wilmington grounds were the class of the league.

Three thousand were on hand for the return of professional baseball to Wilmington but the faithful were sent home in a sour mood after Paterson scored all their runs in the 9th inning to steal a 3-2 win. On April 29 in the opening series Honus Wagner played first base for Paterson and led the attack in a 6-5 win with a triple and a home run that went through a hole in the fence. He also made 16 putouts in a performance that was still talked about around Wilmington 30 years later.

In the ultra-competitive Atlantic League the Wilmington nine was never more than two games from .500 for the first 31 games. They then dropped a three-game series to league-leader Paterson to fall to 16-21 and tumble into fifth place. Worse, ominous signs were cropping up off the field.

The final game with Paterson, on a Saturday, drew only 800 fans, a crowd that “should have been twice that size.” Across town the bicycle races of the Pullman Club, a minor club made up of Pullman Palace employees, pulled over a thousand spectators. Elsewhere, there were rumors that New Haven and the Mets were headed to Troy and Albany and that Wilmington might move to one of the abandoned cities.

Wilmington, under manager Denny Long, won 16 of 22 and glided into second place but the all-too familiar problem of poor attendance dogged the team. A lengthy front page Every Evening editorial implored Wilmington baseball fans to support the efforts of the men behind the team who were delivering good, clean baseball to Delaware. Still, the team appeared on the verge of collapse before New Haven and the Mets were replaced by Philadelphia and Lancaster which stirred a local rivalry.

Games with Lancaster attracted 1500 and 2500 in a homestand crucial to the team’s survival. The series kept the franchise in Wilmington but only 300 fans graced the grounds when the team moved into first place with a 46-39 mark. It was exceedingly frustrating to the backers who saw their team play regularly in front of crowds of 2000 or more in visiting towns.

Injuries undermined the team’s pennant drive and Wilmington cascaded down the list to fourth place, finishing at 60-73. In the front office Long lost $1000 while other owners were making as much as $8000 on their investments. Although the year was a failure, the Atlantic League in 1896 was the first minor league season a Wilmington team had completed from start to finish. There would not be a second campaign, however. Long moved the team to Reading in 1897.

THE AAS AND THE BBS

Wilmington entered the 20th century with no professional baseball and no prospects. In 1901 the management of the Brownson Athletic Club formulated a plan for semi-pro baseball that centered around keeping operating expenses down. Players would be paid on a per game basis, all games would be contested on the Union Street grounds in Wilmington with no travel costs, and the team would remain independent of any league. Manager Harry McSwiney scheduled three or four games a week and constantly adjusted the roster to keep the play of the highest caliber.

Wilmington responded. The games were well-patronized and by August Brownson incorporated the team as the Wilmington Baseball Club, operated by the Wilmington Baseball and Amusement Company. McSwiney, so instrumental in reviving baseball in the city, retired to private business and Thomas Roach was retained as a full-time manager. The Wilmington Baseball Club finished the season playing 103 games, winning 60, losing 41 and tying 2.

The success of the Wilmington Baseball Club did not go unnoticed in the local business community. As the team reorganized for the 1902 campaign they were greeted by a new, rival organization. The Wilmington Baseball and Athletic Association incorporated and built new grounds south of the Market Street bridge. South Side Park was a short 5-minute walk from the downtown business area and was convenient to all city rail lines. The grandstand was erected to accommodate an astounding 4000 fans.

Manager Roach of the Wilmington Baseball Club and the Athletic Association’s manager Jess Frysinger spent lavishly to acquire top players from all over the east to stock the two independent teams. By the time the season opened both teams had developed loyal followings around Wilmington. Ardent backers sported badges to indicate their support for the Athletic Association, known as the AAs, or the Wilmington Baseball Club, the BBs.

The phenomenal success of the independent Wilmington Athletic Association baseball team attracted national attention and spawned souvenirs like this pin.

The AAs, with their superior facilities, attracted much of the early attention. Seven thousand fans poured into the new park for Opening Day, flooding the field and necessitating the adoption of special ground rules for the game. Crowds continued to average more than 5000 through the season. Meanwhile the BBs, playing away from the center of town at the Union Street grounds, played to near capacity crowds of 3000, often on the same day. Wilmington had never seen baseball fever like this.

And the fans of the respective teams did not reserve their passions solely for each other. Four hundred followers of the AAs accompanied their team to Chester and when the steamer returned to the Wilmington & Northern wharf a melee broke out between Wilmington and Chester fans. Some Wilmingtonians jumped overboard into the river and others never did disembark. The steamer pulled away to shouts of “Three cheers for the Wilmington AA!” as Chester fans replied by throwing chairs from the deck.

After a 26-19 start the BBs replaced Roach with Curtis Weigland, a hard-hitting middle infielder. Under his leadership the BBs became one of the strongest semi-pro nines in the country, winning 27 of the next 29 games. They reeled off 22 wins in a row, denied of equalling the independent record of 26 by a 4-1 loss to Pottsville in the opening game of a doubleheader. The majority of the games were tightly played affairs that sent the happy fans home in less than 90 minutes.

As the reputation of the BBs grew the AAs matched them win for win. The AAs built their record to 65-18 and went on a 20-game winning romp of their own, led by catcher Harry Barton, the most popular player ever to wear a Wilmington uniform. The AAs were stopped only when Chester notched four runs with two out in the 9th inning to wrest away an 8-7 triumph.

One of the AA victims was the Brandywine nine of West Chester. In September the Brandywines reorganized and started boasting. The two teams danced around terms of a meeting for two weeks, generating great interest in the two towns, until the sports editor of the Philadelphia Inquirer arranged a match in that city.

The game was played on a winner-take-all basis, with each side putting up $500. In addition, the victor would cart home all the gate receipts. Connie Mack made his field at Twenty-Ninth and Columbia available for only $75. Special trains carried large delegations from West Chester and Wilmington to the game. An enormous crowd of 15,712 paid their way into Shibe Park.

Wilmington tallied in each of the first two innings to grab a 2-1 lead and nursed the tenuous advantage for six more tense innings. In the ninth Newton led off with a double for Brandywine but was doubled off when the next batter lined to second. After a single, the AAs got the last out on a tapper to the mound.

Wilmington partisans swarmed the field carrying the players to the locker room on their shoulders. The fans, equipped with every noisemaking device that could be found, then marched en masse to the Reading Station behind the Philharmonic Band as Wilmington papers were releasing extra editions to announce the 2-1 final.

The owners of the AAs realized a bounty of $4606 from the gate receipts, not including the spoils of the bet. The money was split with 50% going to the owners, the Stirlith brothers, and 50% going to the players and manager. In addition, players claimed to have won an additional $2000 in side bets. The money was carried back to Wilmington in satchels.

Chick Hartley, surely one of the greatest hitters ever produced in Wilmington, pitched the victory. He used his $400 bonus to get married and signed a major league contract. He became disenchanted with the pro game before the season began however and quit baseball. Hartley left Delaware for Philadelphia where he was a policeman on the beat for more than 30 years.

Left out of the frenzied hoopla Weigland of the BBs offered $1000 for a winner-take- all game with the AAs but Frysinger was not interested. Such a confrontation would surely be a duel to the death. The loss of prestige that would shroud the loser could spell financial ruin. As it was the two teams would never meet on the diamond and the continual debate as to which was the better team served to keep interest in both nines at a high pitch.

On the field there was little to choose between the AAs and the BBs. Playing much the same schedule of strong semi-pro teams from Pennsylvania and New Jersey the AAs completed the 1902 season with an 83-34 log; the BBs checked in with an 88-38 mark. The popular local twirler Billy Day led the way for the BBs with 30 wins, six by shutout.

Frysinger was feted nationally in the October 25 edition of Sporting Life in an article titled: “Worthy of Promotion: An Independent Manager Who Made a Great Record Last Season.” The teams’ six wins over major league teams were noted and it was suggested that the manager was destined for a career in the majors. He would, however, die tragically in 1906 at the age of 33 from complications following surgery to remove an appendix.

By 1903 the fervor for the AAs and BBs had lessened not a whit. South Side Park overflowed with 10,500 fans for the first game, the largest crowd ever to witness a baseball game in Delaware. Across town 4500 squeezed onto the Union Street grounds to see the BBs begin play. Each team had an almost complete turnover in personnel but fans quickly adopted new favorites. Both the AAs and BBs started slowly but by midseason each was playing at a .650 clip when suddenly the town was startled to learn the AAs had bought the BBs.

The Stirlith brothers swallowed the Wilmington Baseball Club whole; they purchased the players, the Union Street lease, the uniform and even the charter. The BBs were breaking even but were making no money due to the generous salaries needed to keep top players in Wilmington. Former heavyweight champion John L. Sullivan umpired the last game in the history of the BBs, a shutout win. Their record for 1903 was 54-32; for the three years they stood at 202-111-2, a .645 winning percentage.

The newly merged Wilmington Athletic Association team continued to roll over its opponents, snapping off 31 wins in their final 39 games. With the rivalry dissipated the most talked about moment of the final part of the season was the first home run hit out of South Side Park, one of the most spacious yards in the country. Thomas of Lebanon crushed a ball fully 20 feet over the 350-foot left field wall to make headlines in all the papers. Overall the AA’s finished the year at 91-39, featuring 26 shutouts. Everson led the pitchers with 31 wins and Faulkner notched 29 wins, tossing 76 consecutive scoreless innings at one point.

But the AAs had not heard the last of the BBs.

After the season the AAs represented Delaware in the Tri-State Championship in Philadelphia, against Camden from New Jersey and Harrisburg, skippered by their old manager Jess Frysinger, handling Pennsylvania. Harrisburg won the coin toss gaining the bye and Camden and Wilmington tangled in the first game. It was a sloppy affair with the AAs losing 6-5. The death blows were two home runs knocked over the right field fence by Billy Gray - the former Wilmington BB outfielder. After obtaining his services in the buyout the AAs had released Gray as not being good enough to make their club.

THE MAJOR LEAGUES COME TO DELAWARE

The AAs and the BBs both brought big league nines to Delaware, entertaining the likes of the Philadelphia Phillies, Boston Braves and John McGraw’s New York Giants. Great sluggers like Honus Wagner, Nap Lajoie and Ed Delahanty performed in exhibition games with the locals before wildly enthusiastic crowds.

After the Philadelphia Athletics won the American League pennant in 1902 Connie Mack invited the AA’s to play a benefit game in Philadelphia as part of the victory day parade celebration. The Wilmington team fell behind early but rallied for six runs in the 6th inning to take an 8-7 lead.

The champions quickly regained the advantage to the delight of 11,000 Philly rooters waving white elephants, given out for the occasion. With the score 10-8 Mack brought in his ace hurler, George “Rube” Waddell. Waddell was unquestionably the greatest talent to yet appear in major league baseball but he was as celebrated on his way to the Hall of Fame as much for his childish antics as for his blazing fastball.

Waddell, who was an imposing 6’1” figure on the mound, was said to spend days on the banks of a river fishing when he was supposed to be pitching. “There was delicious humor in many of his vagaries, a vagabond impudence and ingenuousness that made them attractive to the public,” the Columbus Dispatch explained to its readers. In his 1902 seasn Waddell did not pitch his first game for Mack until June 26 but still won 24 games and paced the league with 210 strikeouts.

Rube Waddell was baseball’s first great strikeout pitcher - as he proved in exhibition games in Wilmington.

In his outing against the AAs Waddell closed out the game by striking out Wilmington’s last five hitters, finishing off the final batter after sending his fielders to the bench. It would become part of Waddell’s legend that he routinely performed such feats of bravado but even though Rube waved his fielders in against Baltimore and Boston the players never left their positions. Only against Wilmington did the Athletic players leave Waddell alone against the hitter.

The AAs claimed a measure of revenge the next day when the A’s came to Wilmington for an exhibition game. Waddell was struck by a line drive on his hand and driven from the game as the AAs went on to down the American League champs 4-2.

MINOR LEAGUE BASEBALL - THE TRI-STATE LEAGUE (1904-13)

Flushed with the success of its independent professional team owner Stirlith and manager Frysinger entered the AAs into a loose aggregation of clubs known as the Tri-State League. Joining Wilmington in the new venture were nines from Camden, Williamsport, Altoona, Lebanon, York and Harrisburg. For the next decade Wilmington’s professional baseball fortunes would be cast with this sometimes maddening, sometimes remarkable and always resourceful organization.

A crowd estimated at over 10,000 turned out for the season opener at South Side Park. The players paraded to the grounds in a special trolley car behind the Philharmonic band. Upon entering the park they were greeted with fully ten minutes of applause. Rising to the occasion, the AAs rallied for two runs in the ninth inning to win a 7-6 thriller.

The town buzzed with the goings-on “across the bridge.” The lowest admission prices in the circuit, 20 cents and 10 cents extra for the grandstand, brought Delawareans “league ball at amateur prices.” But the ills that would haunt the Tri-State League like a prolonged batting slump were already fomenting. On June 18 Camden, which had won only four of its first two dozen games, disbanded. Wilmington, despite a winning record, was thrust into next-to-last place.

More insidious was the escalation of salaries among the teams. As independent teams with no league regulation players jumped routinelyto the highest bidder. Salaries became so great that some major leaguers jumped into the Tri-State League. With its low admissions and a lack of attractive Saturday home dates Wilmington couldn’t compete for the best players.

The AAs were built on speed but pitching woes spawned a rash of one-run losses that condemned Wilmington to last place. They slumped to 27-41 and the owners considered transferring the entire York team to Delaware but they stuck with the original squad. Unable and unwilling to hire replacements for stars spirited away by rival clubs Frysinger found himself with only nine players to field and five of them were pitchers.

For the first time in history a league cancelled Wilmington home games for fear of no attendance. The team limped home with a final record of 41-61. Wilmington had begun the 1904 season as the best-paying city in the Tri-State League. But after a year of raiding and warring against other teams there was little thought of re-joining for 1905.

Baseball rumors of the upcoming season swirled around Wilmington for the entire off-season. Fans were anxious for the new baseball campaign but had no pro league representative. The Tri-State League - now minus its New Jersey and Delaware representatives - kicked off with six Pennsylvania teams in the fold. Wire reports indicated things had not changed in the tumultuous circuit: “So far only three of the umpires of the Tri-State League have been assaulted this season.” And it was only May 7.

In early June Wilmington was summoned to replace the faltering Lebanon franchise in the Tri-State. Wilmington was forced to assume Lebanon’s 4-28 record but they jumped out with three wins, including one against defending champion York, and crowds of three and four thousand supported the team.

But soon the AAs’ play began to approach its predecessor, tumbling to 21-67. They were 14 games out of next-to-last place. The visiting towns weren’t enticing enough to pull fans and the amateur games began outdrawing the Tri-State League. In an extremely tight pennant race Wilmington sold its last three home games to York. It was a legal move but the league grumblings increased when Wilmington surrendered two runs in the bottom of the ninth to lose the series opener. Then the AAs shocked the Yorksters 3-2 and 11-6 in a doubleheader to deliver the Tri-State flag to Williamsport.

There was no Tri-State League ball for Wilmington in 1906 but the next year the Association joined the National Baseball Commission in an attempt to protect players and keep salaries down with a cap. Wilmington was regarded as the linchpin in the organization and was awarded a majority of the attractive Saturday home dates. The 25- man team left for spring practice in Portsmouth, Virginia on March 30 while enthusiasm back home in Delaware was higher than any season yet. South Side Park was fitted with new bleachers and the grandstand was improved to feature folding opera chairs. Seating capacity was increased to 6000 and every seat was filled for Opening Day.

Despite the heftiest payroll in the league the Wilmington “Peaches” stumbled to a 1-9 start, swatting the ball at an anemic .182 clip. Tension mounted on and off the field. When outfielder Rube Vinson, a former American League outfielder and Dover native, was tossed out of a South Side Park game in a bellicose argument with an umpire he waved encouragement to several hundred fans who stormed the field. It was the ugliest incident in Wilmington baseball history; eight policeman were required to escort the besieged official from the grounds. Vinson was suspended and soon traded but the tone for the season had been established.

The Peaches cascaded to a lowly 3-16 as the press bemoaned hard luck and bad umpiring calls. Owner Chris Connelly changed managers and attempted to strengthen his roster with former major league talent. Hank Mathewson took the hill for Wilmington but hardly invoked images of his Hall-of-Fame pitching brother Christy when he didn’t survive the first inning, yielding four runs and never appearing again.

The team continued to struggle and changed managers again. This time popular catcher Mike Grady from Kennett Square took the helm. Grady had enjoyed an eleven-year career in the major leagues, compiling a .294 lifetime batting average and smacking 35 home runs in the dead ball era. But he is best remembered for making four errors on a single play while filling in as a third baseman for the New York Giants in 1899.

His time with the Peaches more resembled his follies as an infielder than his triumphs as a backstop. Grady pushed the Peaches all the way to 5th place but they remained mired there for the rest of the year. Through all the travails the fans continued to support the team, although many were calling for even Grady’s scalp.

The dismal performance of the Wilmington Peaches left fans in a surly mood. Dover native native Rube Vinson incited a riot when he called for fan support in an argument with an umpire.

The season ended in farce as Johnstown and Wilmington played the league finale in 57 minutes to get the season over with, not running the bases and being purposely put out. The crowd of nearly 2000 left totally disgusted with its 43-79 team. But even the rancid exhibitions of 1907 couldn’t dissuade Wilmington baseball fanatics from their game.

Eight teams began the 1908 Tri-State campaign and Wilmington actually started 16-16. Then a two-week downturn sent the Peaches plummeting into the familiar environs of last place. They captured only 4 of 26 August games but attendance still averaged nearly 1500. When stadium rent was raised to $25 a game the owners decided to play out the season on the road, ending the longest continuous stretch of professional baseball in Wilmington history.

The “homeless team” stumbled in as the league’s tailender, dropping 87 games against only 40 wins. They were 42 games out of first. Another several thousand dollars in the red, the owners decided to abandon the Tri-State League. In four years the Peaches had finished last, last, next-to-last, and last - despite being the highest paid team in the league most of that span. Never at any point in the season had the team reached higher than fifth place. Their four-year mark was 157-318, winning barely more than three of every ten games.

Wilmington could not remain out of league ball for long. With over 110,000 people it was by far the largest unattached city on the east coast. The economy was booming and amateur games were always well-attended. As a baseball town there was no more attractive or eligible temptress to potential owners than Wilmington.

By 1911 plans were ready to re-join the Tri-State. The fans were waiting; 2500 showed up for the season opener on a bitter April afternoon. The Wilmington Chicks, as they were now known, displayed pitching woes from the start. They returned from a bad road trip and committed ten errors. It was reported that some of the misplays looked intentional and the games were called “disgusting articles of baseball.”

When a former Wilmington hurler twirled a 5-hitter against the Chicks the team was savaged in the local press: “Pitcher Daly, who, when with Wilmington was banged all over the field by every old club that came along and who since joining Altoona has also been hit to all corners of the lot, simply played with the locals yesterday.” As the team began playing better the hitting stopped and the Chicks settled once again into the basement.

Still, 3000 fans turned out for Saturday home games and even a modest four-game winning streak stirred local passions. But the team seemed jinxed on and off the field. When Weeks, the team’s best all-around outfielder, left the team because his mother was ill it was noted that, “It is seldom that a ball player gives up baseball entirely because his mother is ill.” Between the white lines the Chicks suffered through an unbearable 49 one-run defeats.

They finished the 1911 campaign in last place, 12.5 games from 7th and 39 games away from first place. The owners Peter Cassiday and Thomas Brown admitted they got off to a bad start by following poor advice on securing players. It was the worst year ever financially for any Wilmington team in the Tri-State League but the owners proved their mettle as sports- men by not resorting to benefits and “$1 games” - where the owners asked a dollar admission rather than 25 cents - to recoup losses.

The 1912 season held the dual promise of a new beginning: a switch to the revitalized Union Street grounds and the hiring of a new manager who had apprenticed under the greatest manager of his day, John McGraw - Jimmy Jackson. Jackson, a hard-hitting centerfielder, kept the team bobbing around .500 for the entire season, finishing in fifth place at 58-55.

Strangely, as the team improved the fans became apathetic. In the midst of an 8-game winning streak fewer than 500 people dotted the stands. The main attraction at Union Street seemed to be the Bull Durham tobacco advertising sign at the park. The company awarded 72 bags of tobacco for any home run and $50 for any homer striking the bullseye. For the season 2500 round-trippers were hit in professional baseball resulting in 180,000 bags of tobacco. There were only 208 bulls-eyes and none of the 29 balls hit out of the Wilmington park plunked the Bull Durham bull.

Jim Jackson, a rare college man in the early days of baseball, turned the Wilmington entry in the Tri-State League, into a winning nine.

The next year Jackson had his troops at the head of the Tri-State list from Opening Day. Combining timely hitting and solid pitching the Chicks raced to a 6-1 record and were out of first place for only 24 hours the entire season. With 30 games left the Chicks had gouged a 7-game lead and the owners dug a five-foot hole in centerfield for the pennant pole. When they clinched the pennant thousands packed the streets of Wilmington to enjoy “Noise Day” as 1000 athletes from every baseball club in the city marched to the baseball park.

The 1914 season looked much the same as the Chicks leaped out to a 26-18 mark and first place but the Chicks, the Tri-State League and all of minor league baseball were suffering. A third major league, the Federal League, had siphoned off the cream of the minor league talent, especially from a Class B league like the Tri-State. The quality of ball suffered and the fans noticed.

The Chicks were forced to go with younger players as Jackson moaned that, “the men sent to me are weaker than some on the town lots.” When clean-up hitter Jackson went down with a broken hand the irreversible decline began. The owners fell behind on player salaries and the team limped home fourth at 47-63.

The Federal League did not survive but it succeeded in killing off the Tri-State League. After nearly a decade of frustration Wilmington had finally fielded a winner only to have the league fold.

MINOR LEAGUE BASEBALL - THE UNION LEAGUE (1908)

The Union League held promise as the strongest minor league ever to play in Wilmington. Its tight geographic boundaries with Brooklyn to the north, Washington to the south and Reading to the west promised economical travel and the inclusion of Philadelphia, Baltimore, Washington and New York gave it the greatest population base outside the major leagues.

The Wilmington ownership leased the Riverview grounds at 29th and Market and spared no expense in outfitting the park. Bleachers to accommodate nearly 3000 extra fans were installed and 1200 seats with backs were placed around the infield. An innovative two rows of box seats lined the perimeter of the field. Between the lines the first grass infield in Delaware was groomed to perfection.

The new Wilmington team bested Delaware College and the Philadelphia Phillies in exhibitions and more than 4000 fans poured out of Wilmington down Market Street for the gala season opener. Within a month the team was firmly entrenched in first place with a 13-5 start.

But the enterprise was losing money from the start. The Riverview grounds just seemed to be too far out of the city for most fans, especially for a brand of ball the now sophisticated Wilmington baseball fan could recognize as decidedly inferior. On May 26 the team failed to receive its wages and broke off a trip to Brooklyn. The next day the first place team disbanded. A week later the Union League, stripped of all its preseason expectations, dissolved as well.

MINOR LEAGUE BASEBALL - THE ATLANTIC LEAGUE (1916)

Once again the lure of a town of 100,000 people without baseball proved irresistible to area sportsmen. Dr. Leon Van Horn of Philadelphia bought a Class B Atlantic League franchise for Wilmington. A nickname contest was held and the name “Diamonds” was chosen for the new team but fan response was only luke-warm.

After two dozen games the Diamonds had gone through three managers and only three players remained from Opening Day. There were many rain-outs and the other teams in the circuit - Pottsville, Paterson, Reading, Allentown and Easton - were not big draws. With the team 11-12 the players had not been paid and took possession of the gate, splitting receipts among the 16 men. Five games later the Diamonds were gone, only four days before the very shaky Atlantic League disappeared altogether.

MINOR LEAGUE BASEBALL - THE EASTERN SHORE LEAGUE (1922-26)

The first Delaware town outside Wilmington to enjoy minor league baseball was Laurel. Together with five Maryland towns - Pocomoke City, Crisfield, Cambridge, Salisbury and Parksley - Laurel was a charter member of the Eastern Shore League, a “baby” Class D minor league. The longest bus ride in this lowest rung of professional baseball was a short jump of 85 miles. There were no overnight stays and all ballparks were within walking distance of the center of town.

In Laurel, a crossroads town of 4000, a tentacular stone road from the new DuPont Highway aided baseball fans from neighboring Delaware towns to the north in attending the games. The inaugural campaign for the Shore League was fraught with unpleasantries. Open betting at the games hindered attendance, especially by women and families. Attacks on umpires, always a distasteful part of early-day baseball on the Peninsula, were frequent and violent. At Crisfield a fan brutally beat an umpire while a game was in progress and there were several incidents in Laurel as well.

On the field the Laurel Chicks challenged for the lead early but were never able to get back to the break-even mark after reaching 5-5. The Chicks featured only two Delaware boys - Dorsey Donohoe and Dal Culver of Seaford - but were well-supported by the town. They won 16 of their final 25 games to finish fourth at 34-35.

In 1923 league officials took firm steps to curb its gambling and violence problems. Expansion brought the Dover Dobbins and Milford Sand Snipes into the circuit. At the state capital a new park with a grandstand for several thousand spectators was built at Ninth Street and Little Creek Road. There was a parking lot for 500 automobiles and 2000 turned out for the Dobbins’ home opener.

The 1923 season started well for Dover, Laurel and Milford. The Delaware troika joined defending champion Parksley in a 4-way tie for top honors at 16-13. Play was competitive throughout the league and fans were treated to good ball from the rookies who for the most part were not allowed by Eastern Shore rules to have been in the professional game before.

When Wilmington once again proved incapable of supporting pro baseball the Milford Sand Snipes bought their star players and manager. The maneuver backfired when Milford was ruled to have used several players from a higher class than Class D. The Sand Snipes forfeited nine games and disbanded on July 4.

After the holiday attendance slumped in all the Eastern Shore towns, save Dover and Salisbury. The Dobbins, led by a 20-year old future Hall-of-Famer fresh out of Boston University named Mickey Cochrane, reeled off 12 straight wins to capture the pennant at 50-23. Cochrane played under the alias “Frank King” since he was still on scholarship to the Terriers. Laurel improved to third place at 42-30. In post-season play Dover whipped Martinsburg, West Virginia of the Blue Ridge League four games to two in the “Five State Series.”

The 1924 Eastern Shore League race was one of the most exciting in professional baseball history. For the first half of the season Dover dominated with a 25-14 log but the Dobbins’ hitters slumped and they dropped into fourth place. With six games remaining only three games separated the top five teams.

The lone Shore League entry out of the pennant sweepstakes was Easton, under the direction of the old Philadelphia Athletics star Frank “Home Run” Baker. Easton started 2-22 despite the presence of 18-year old homeboy Jimmy Foxx behind the plate. Baker called his young catcher, “the most promising player I have ever seen.” Foxx, destined to be the greatest slugger of his time behind Babe Ruth, could not pull his team from the cellar in his first year of professional ball. He finished at .296 with 10 home runs in 260 at-bats.

Hall-of-Fame Slugger Jimmy Foxx got his start in the Eastern League.

Dover stopped hitting altogether and Laurel came up short in the 1924 stretch drive. The Dobbins’ team batting average was a microscopic .229 for the season and they connected on a league-low 43 home runs. Things were worse at Laurel; the owners were $2400 in debt and sold all its players to Salisbury as the franchise dropped out of the league.

Carrying on as Delaware’s sole Eastern Shore League representative Dover struggled through a mediocre 1925 campaign but once again challenged for top honors in 1926. It was a troubled year on the Peninsula as five teams were found guilty of class violations - using players too experienced for the rookie league.

The Dobbins held to a four-game lead late in the season when they were hit with a 23-game penalty. Dover protested and the ruling was overturned, re-establishing the Dobbins in first place. But other franchises pressed the issue until Dover was stripped of 23 games again and the season ended with management still offering evidence in defense of the legality of its roster.

Disgusted with league policies Dover dropped out of the Eastern Shore League after the 1926 season. The league resisted obituaries for one more year before a lack of fans closed down professional baseball on the Delmarva Peninsula.

THE SHAUGNESSEY PLAYOFFS

Playoffs are so woven into the fabric of sports that it feels like they naturally existed from the beginning. Not so.

Professional baseball has always been about one thing - money. Especially in the low minor leagues where short-pocketed owners could not long survive spiraling costs and sparse crowds. This was especially troubling when teams would fall hopelessly behind in the year-long pennant chase.

Enter Frank “Shag” Shaugnessy, an innovative football coach who introduced the option play at Yale University. Shaugnessy also got into a few games in the Philadelphia Athletics and Washington Senators outfields in the early 1900s. Shaughnessy managed 19 seasons in the minor leagues and in 1933 was helming the International League. it was his idea in 1933 to pit the league’s top four teams against one another in a multi-game series - usually a best-of-seven to pad the coffers even further.

The Shaughnessy playoff system was embraced around minor league baseball. The National Hockey League was the firstto use playoffs at the major league level and today, while Shaughnessy’s name has been long forgotten, playoffs are ubiquitous in sports.

Frank Shaughnessy invented the modern playoff system.

Nowadays, the best team in baseball’s regular season is quickly cast aside should that success not translate into wins throughout the playoffs. But in the early years the playoffs were a novelty and it was still the regular season title that carried the most prestige. This became especially true as more and more pennant-winning teams expired in the Shaugnessey Playoff system. The Wilmington Blue Rocks, for instance, won three pennants but only once completed the season with a playoff championship.

Regular season titleists were especially vulnerable in the first round of the playoff whirl. Dover’s best team, assembled in 1940, after capturing the flag with a .600 winning percentage, exited quietly in the semi-finals. Conversely, the year before a third-place Dover nine embarrassed Federalsburg, which had finished the year nearly 20 games ahead, 14-3, 12-8 and 13-1.

Increasingly these playoffs came to be regarded for what they were - money-making exhibitions. The fad faded in the 1930s and 1940s until it was revived by the proliferation of expansion teams in major league sports.

MINOR LEAGUE BASEBALL - THE INTERSTATE LEAGUE (1940-52)

The concept of the farm system breathed new life into the minor leagues in the 1930s. Feeder teams designed to funnel talent to the big league clubs blanketed the country. In Wilmington in 1940 the Class B Interstate League franchise became the first farm team wholly owned by Connie Mack and his Philadelphia A’s. For the next 13 years the Wilmington Blue Rocks would compile one of the most enviable records in the history of minor league baseball.

For seven consecutive years Wilmington finished first or second; only twice did the Rocks miss the Interstate playoffs, reserved for the top four teams. Four times the Rocks brought the Governors Cup, awarded to the playoff winner, home to Delaware.

A newspaper contest was used to select the team nickname and over 5000 entries poured in. “Blue Rocks” was chosen after a three-day struggle with the runner-up “Colonists.” The winner was 73-year old Robert Miller who remembered the famed blue granite of his youth along the Brandywine River. He received a season pass for his prize, as did Wesley Taylor who submitted “Blue Rock.”

On the field the Rocks were guided by old A’s star pitcher and soon to be Hall-of-Famer, Chief Bender. Seven thousand fans jammed Wilmington Park for the first game with Trenton and watched the Blue Rocks triumph 3-1 behind a six-hitter by Philadelphia’s Sam Lowry.

For the first half of the 140-game season the Rocks struggled. In the first 50 games Bender auditioned 50 players for the blue and white. With Wilmington mired in fourth place at 29-28 Bender was replaced. Under new skipper Charlie Berry the Blue Rocks ran off nine straight wins and spurted to second place at the finish, although they were quickly eliminated by Lancaster in the playoffs.

Centerfielder Elmer Valo won the 1940 batting title at .364. He returned the next year before graduating to Philadelphia and becoming the best player ever produced for the A’s by the Blue Rocks. But the biggest success in Wilmington was at the gate. The Blue Rocks established a new Class B attendance record in 1940 with 145,643.

Charles Albert “Chief” Bender was part Chippewa Indian. He won 212 big league games and was the first manager of the Wilmington Blue Rocks.

The 1941 edition of the Rocks started strongly, building a three-game lead at 30-14 before injuries slowed the team. Despite a final mark of 64-62 Wilmington finished fifth, one spot out of postseason play. The 1942 race boiled down to only the Blue Rocks and the Hagerstown Owls, with the rest of the league 11 games back.

In August the Rocks reeled off 13 straight wins, including a minor league record five consecutive shutouts. The regular season ended with Wilmington 1/2 game short of the pennant when their final game was rained out. But the Blue Rocks’ starting pitching overwhelmed their opponents in the playoffs for the Governors Cup. Allentown fell three games to one in the semi-finals bringing the expected match-up with Hagerstown. Certainly not helped by a team station wagon overturning on the journey between Delaware and Maryland, the Owls managed only ten runs as they were outscored by the Blue Rocks 31-10 in losing four games to one.

The World War II years were characterized by big hitting and crowd-pleasing offense - and a change of ownership. Before the 1943 season the fences at Wilmington Park were moved in considerably - especially in right field where one of the longest pokes in professional baseball was reduced from 390 feet to 320 feet. In 1944 the Rocks slugged at a .285 clip - and finished 5th in the six-team league in team batting average. Altogether there were thirty .300 hitters in the Interstate League in 1944.

Prior to the 1944 season Bob Carpenter, Jr., whose father owned the Philadelphia Phillies, completed arrangements to take control of the Blue Rocks as well. Carpenter, an ex-Duke footballer and accomplished badminton player, had been President of the Wilmington club from its inception and had purchased 50% of the team stock with his father years earlier. From this point the Wilmington Blue Rocks would be a Phillies farm team.

With the war over, Wilmington was ready for baseball. More than four thousand turned out for the season opener to see the Rocks whip 1945 champion Lancaster 17-1. And the fans didn’t stop coming until a record 172,531 passed through the turnstiles. And the Rocks put on quite a show. Their final home record was 50-19 and they never lost a home series.