Football in Delaware

Delaware Field Club

The Delaware Field Club, Delaware’s first organization for outdoor sports, started modestly on the front porch of Henry Tatnall’s house on Jefferson Street in Wilmington in 1882. The Tatnalls supplied the adhesive to bond the cricket-playing talent of the city of Wilmington. The Delaware Cricket Club was formed and negotiations were quickly underway for a club grounds which were secured at Twenty-Third and West streets, far out across the Brandywine River.

Within a fortnight a cricket crease had been laid out along with courts for tennis and open spaces for croquet and other games. One game that would never be played on the new grounds was baseball, considered too boisterous and commonplace for such an exclusive club. A strong baseball nine was eventually formed from the Field Club but many of the young members played under assumed names so as to not muddy their reputations in the local business community.

The grounds at Brandywine Village were almost two miles from center city and transportation was problematic. In fact, it was non-existent. Trolley lines did not run that far out of the city and an omnibus was hired to ferry passengers out to the Cricket Club for a 5-cent round trip fare. With a capacity of but 12 the Pioneer Coach Company was busy indeed when the flag flew above the clubhouse signaling to downtown members and fans that a game was afoot.

The club was incorporated on March 23, 1885 as a stock company and changed its name to the Delaware Field Club. William Canby was elected president and stockholders formed a “Who’s Who of Delaware” society: Bancroft, Bayard, Carpenter, Haskell and du Pont. From this aristocratic group would emerge Delaware’s first great football team.

In 1890 the Delaware Field Club moved to a spacious new headquarters in Elsmere which was transformed into some of the finest sporting ground in the country. The seven acres, enclosed with a 12-foot fence, featured 24 tennis courts, a baseball field and a cricket field. The graceful clubhouse included a bowling alley and shuffleboard. When the Club moved to its new grounds a new sport had been added to the roster of activities: football.

With hard practice and superior precision the Delaware Field Club dominated the other novice in-state teams. They instead reached across state borders to forge rivalries with strong collegiate squads such as the Princeton University sophomores and the St. John’s eleven of Baltimore. It wasn’t until Halloween day 1891 that the rest of football playing Delaware caught up with the Field Club.

The lead account of the Delaware Field Club-Delaware College game that day could hardly be described as low-key: “But who will ever forget the great contest in the Newark meadows of Saturday evening October 31! Nothing like it was ever seen or heard of in Delaware before. It inaugurated the real commencement of football playing in the state.” The college boys ground out a 4-0 upset win in Pie’s Meadow that day, a victory no informed observer could have anticipated. Only two years previously Delaware College had been routed 74-0 by the Field Club in its first game ever.

It was not only the first loss of the Delaware Field Club to an in-state rival but the first points ever surrendered by the Field Club. For the rematch in December of 1892 officials in Delaware City offered each club $100 to meet in that town. Both teams and their fans loaded boats and the colorful convoy of the red-and-black Delaware Field Club and the gold-and-blue Delaware College made its way down the Delaware River.

The Field Club was coming off a bitter 12-6 Thanksgiving loss to St. John’s and looked to this state championship game for redemption. In a titanic struggle neither team was able to penetrate the other’s defenses and the game ended in scoreless tie. It was the last big game for the Delaware Field Club. The next year the team lost several key players and disbanded. The future glory of the Delaware Field Club lay on the golf links and not the gridiron.

THE WARREN ATHLETIC CLUB

The most famous of Delaware’s 19th century football clubs, the Warren Athletic Club, was organized in April 1883 as an athletic and social club, based in a second story room of the Washington Fire Company, then located at Third and French Streets. The club was mostly comprised of members of the fire company.

Within a few years the success of the club had spawned membership applications from men across the city, over 1000 in all. It was one of the largest athletic clubs in the country. Warren men were prominent in nearly every type of athletic endeavor for the next decade but it was football where Warren fame lingered. Warren football began in 1889 and by 1893 the club was engaging the best elevens in America.

The Warrens could handle any opposing eleven except the national champion Penn Quakers.

That year Warren hosted a strong St. John’s club from Baltimore on Thanksgiving, losing 6-4 before 3600 frenzied enthusiasts. The next week Warren lost “only” 24-0 in sheets of rain to national champion University of Pennsylvania. Keeping the score even for ten minutes was considered the greatest achievement in Warren football history. Warren even managed to score the only touchdown of the season against Penn but the play was disallowed as a forward pass.

By 1897 Warren had lost only one game in three years against teams other than the University of Pennsylvania. Their greatest in-state rival, the YMCA, had by now abandoned football leaving the Warren orange and black as the colors of choice for Wilmington gridiron fans. The biggest games could bring out as many as 5000 supporters for the exploits of such stars as halfback George “Kitten” Prentiss, considered the greatest Delaware football player of the 19th century. Prentiss was a 10-second sprinter who later pitched major league baseball until dying of typhoid fever in 1902.

As popular as the Warren Athletic Club became by the end of the 1890s financial pressures were eroding the legendary organization. Their final gridiron glory came on Thanksgiving Day 1897 when the Warren management lured the United States Artillery School of Fort Monroe, Virginia to Wilmington. The U.S. Artillery was the greatest football attraction ever seen in Delaware to that time, undefeated in four years and the best team outside the so-called Big Four: Penn, Yale, Princeton and Harvard. Early in the game Prentiss scored on a five-yard run to cap a long drive and the Warrens held off the Artillerymen the rest of the way to win 4-0.

The glory days had ended but for the next fifty years, when Delawareans talked football, they compared teams to the Warren Club.

THE ORANGE ATHLETIC CLUB

The Orange Athletic Club began playing football in 1897, engaging lightweight teams around Wilmington for several seasons. With the demise of the Warrens the Orange gradually assumed the mantle of Wilmington’s “premiere” eleven.

By 1905 their reputation as the best team on the South Side Park grounds was firmly established. That year the Orange completed a 5-1-1 campaign, outscoring their opponents 112-9. Those nine points were all surrendered in their only setback, a 9-0 loss to Philadelphia’s Pennsylvania Railroad YMCA - a squad comprised of former college stars.

In 1906 the Orange finally got the tough schedule the team deserved. They travelled to Ohio for a game with the Massillon Tigers, an aggregation of Western collegiate all-stars. The Tigers were a prehistoric football phenomenon - far and away the best team in the country. Their owner reportedly had a standing offer of $100,000 to any team that could defeat the Tigers. The minimum admission ticket to a Tigers game in Massillon was $1.00 at a time when most clubs were barely able to collect fifty cents for their best seats.

The Orange were not the team to threaten that $100,000 guarantee. Outweighed by nearly 50 pounds per man they fought the Tigers to a standstill for the first ten minutes and came as close to driving to the Tiger end zone as any team ever had but the Delaware boys were used to 20-minute halves, not the 30 they played in Ohio. Wearing down, the Orange were crushed 77-0 but won a national reputation for their fine performance.

But the Orange had come along at the wrong time. Big-time college football was upon the land and nearby Philadelphia was a focal point for many of America’s most anticipated contests. Fan support for the Orange was never great - crowds of 500 were the rule - and a money-making season was out of the question. Orange management realized the situation and only played to get enough money ahead by season’s end to throw the players a banquet and give them a team photo.

By 1909, after several financially shaky seasons, even that modest goal was unobtainable. The Orange disbanded, having suffered only one defeat to a local team ever - back in 1898 to the Franklin eleven. No more would an independent football team carry Delaware’s colors to distant gridirons; from this point that duty would be the special reserve of the Delaware College Blue Hens.

THE WILMINGTON CLIPPERS (1937-49)

At the height of the Depression, in the face of previous failures in professional boxing and baseball, minor league football came to Delaware in 1937. During the closely watched pre-season half of Wilmington was ecstatic over Lammot du Pont, Jr.’s new professional football team while the other half warily predicted doom. It turned out that both sides were right.

The independent Clippers arranged an ambitious schedule which included four National Football League teams. Du Pont and team president John De Luca put player procurement in the hands of veteran football man Dutch Slagle. Slagle’s most important recruit was Walt Masters, a former University of Pennsylvania star and Washington Senators pitcher, who was expected to provide running, kicking and passing from his halfback position.

For local flavor Slagle added Joe Scannell, who was quickly dropped, and Vic Willis, Jr. Willis, a 6’6”, 190-pound end out of the University of Maryland, was employed as a chemist and turned down several more lucrative offers to stay close to home. The “elongated wingman” played half the season before being released as the Clippers’ last Delaware connection.

More than 4000 fans paid the highest prices ever seen for a Delaware sporting event to see the Clippers clash with the Philadelphia Eagles at Pennsy Field to kick off the 1937 season. Box seats fetched $2.50, although admission to the game could be gained for as little as 40 cents. The Wilmington faithful went home only mildly disappointed by a 14-6 loss in a defensive struggle that saw the Clippers outgunned 145 yards to 15.

Singled out for his outstanding play on the line of scrimmage was #18, a stocky warrior from Fordham named Vince Lombardi. Lombardi broke his nose in a scrimmage the following week but was back in the starting line-up for the Clippers first win, a 25-7 dismantling of the Richmond Arrows. Lombardi played the entire 1937 season with the Clippers, his only year of professional play, appearing in 10 of the 11 games and starting five before leaving Delaware for other gridiron adventures.

A broken nose playing with the Clippers helped Vince Lombardi, here pictured as Green Bay Packers coach with quarterback Bart Starr, decide that his football future did not lie in playing.

As the season progressed Slagle’s passing attack matured and the defense began dominating the Clippers’ minor league opponents. Wilmington finished with 7 wins in 8 games against these teams but lost all three exhibition games against the NFL. The cost of this success was high. Slagle brought in several high-salaried ex-NFL players and despite strong fan support the Clippers lost plenty of Lammot du Pont’s money.

New coach Masters forged an impressive 9-3 record for the Clippers in their second year. The “Fleet,” as they were nicknamed, carried their red and blue colors to the American Association and pre-season interest for 1939 was the highest yet. A huge crowd of 5500 saw Wilmington fall 16-0 to the NFL Brooklyn Dodgers in the Friday night opener.

The passing duo of Masters and Jack Ferrante connected on a league record 9 touchdowns in 1939 as the Clippers began to perform before overflow crowds. The Clippers allowed only two touchdowns in the first six league games and finished the year tied with the Newark Bears, a farm team of the Chicago Bears, at 6-2-1. George Halas sent his star Chicago quarterback Sid Luckman to guide Newark in the championship game over the howling protests of the Clippers. More than a thousand Wilmington fans joined the 13,500 in Newark to watch the Fleet dominate the game but lose 13-6 to a late touchdown throw by Luckman. An official Clippers’ protest of Luckman’s appearance was overruled and the Bears were champions.

The Clippers remained strong in 1940, racing out to a 4-0-1 start, including a 13-7 revenge win over Newark. The talented Fleet outplayed the Philadelphia Eagles 16-14, the first time any American Association team had beaten an NFL team. Wilmington lost momentum after the historic win and barely stumbled into the playoffs. Once there, the Clippers stopped the Paterson Panthers 11-8 in the first round after getting a safety from the strange rule of a pass hitting the goalpost. Wilmington lost in the finals for the second year in a row, 17-7 to an old nemesis, the Jersey City Giants.

New coach George Venoroso installed a T-formation offense for 1941 to which the Clippers were slow to adjust. After going winless in their first four games the Fleet began to rally and scored a 28-21 win over league leader Paterson to gain the fourth and final spot in the playoffs. Many in the crowd of more than 6000 considered it the best football ever played in Wilmington.

With Venoroso’s passing game now polished the Clippers ran all over the Panthers 33-0 on a wet and windy December afternoon in their first ever home playoff game. In the finals Wilmington scored all 21 points in a big third quarter to win the championship 21-13 over the Long Island Indians. Four Clippers made the All-League team - Ed Michaels at guard, Scrapper Farrell and Les Dodson in the backfield and Herschel Giddens at tackle. Three other starters from the strongest Clippers eleven yet were named to the second team.

World War II began taking a toll on the American Football Association as early as 1940. Tex Coker, Wilmington’s stalwart at center had played in all 51 Clipper games before being called to National Guard duty late that year. With America at war in 1942 the American Association suspended operations. Even though the team had still never made a profit du Pont decided to continue the Clippers as an independent team.

The Fleet were the strongest football team outside the NFL in 1942. They rolled over opponents by scores like 38-0, 42-6, 59-9, 34-0, 70-0, 28-0 and 77-0. In their first three games 14 different players scored. Searching for quality opponents the Clippers engaged the New England professional champs, the Hartford Blues and scored 7 of the first 11 times they touched the ball in a 48-7 romp.

The fans grumbled about these lopsided games and thirst for a real game was so great that fans were turned away from Wilmington Park when the Philadelphia Eagles came to town. The Clippers spotted their NFL foe three touchdowns before roaring back to tie 21-21. The Fleet threw for 182 yards, the Eagles only 30. With the caliber of opposition severely reduced the Clippers suspended operations after the 1942 season for the duration of the war.

The Wilmington Clippers - known to their devoted fans as “The Fleet” - were the strongest team outside the National Football League in the early 1940s.

The Clippers kicked off again in 1946 as a Washington Redskins farm team. The fans were eager but the Fleet was weak and as the losses mounted, the gate dwindled. Wilmington was outscored 184 to 57 for the year and didn’t score a touchdown at home until the final game when they got a 15-yard fumble recovery to start the game.

The All-America Conference, a rival major league to the NFL, bled talent from minor league clubs like the Clippers and the team struggled on for several years with limited success. A mediocre team squeaked into the finals in 1948 but surrendered 17 second-half points to lose 24-14. In 1949 six home games attracted only 7968 fans, a far cry from the 37,566 in the championship year of 1941. The 5-5 Clippers had to win their last game to gain the playoffs where they were rudely dismissed 66-0 by Richmond.

It was the worst - and last - loss for the Wilmington Clippers. After a painful season in which his losses were estimated at $100,000, Lammot du Pont, Jr. finally pulled the plug on Delaware’s all-time best professional football team before the 1950 season.

THE EASTERN PROFESSIONAL FOOTBALL LEAGUE (1944)

In 1944 Local 36 of the Wilmington Shipbuilders gained entry into the 8-team Eastern Professional Football League. After nearly three years of war interest was high in the new team at the outset as 3000 people turned out for a 20-20 tie with Chester. A typical crowd for the season was 1500 as the Shipbuilders, featuring local stars Bob Riley and Lou Brooks, reached the playoffs despite a 3-4-1 mark.

Wilmington won their semi-final against Camden 3-0 on a 30-yard field goal with under 2:00 remaining but conditions in the league were deteriorating. The field for the championship game at Frankford was in such bad condition several players had to be talked into suiting up. Only 250 fans were scattered around the stands to see a very bad football game. Wilmington brought home the title in its only year in existence when a bad snap on a punt led to a 2-yard drive for the only score of the game.

Samuel H. Baynard was a watchmaker by trade but he would drift out of the jewelry business into banking as the years wound down on the 19th century. In 1900, at the age of 49, he joined the Wilmington Board of Park Commissioners, beginning a quarter-century of work developing North Brandywine Park. In 1912 he paid for the leveling of ground to create the Baynard Athletic Grounds. He continued to pour money into the nascent facility: a quarter-mile cinder track and a concrete grandstand in 1921 and the acquisition of adjacent cottages to be converted into sports storage houses and locker rooms. Since officially opening on June 24, 1922 Baynard Stadium has hosted many of the city’s premier events in football, track and soccer.

THE NORTH AMERICAN FOOTBALL LEAGUE (1965)

In 1965 Wilmington was represented in a curious aggregation known as the North American Football League. The league’s six teams were split into two geographically diverse divisions - the Northern Division included teams in Pennsylvania and Maryland as well as Delaware. The Southern Division was truly that - Mobile and Huntsville in Alabama and Lakeland, Florida. The Comets, as the Wilmington entry was known, opened the season with 21 Delaware-born players and ex-Clipper Jack Ferrante as coach.

The Comets began play before a curious band of 3410 in the 44,000-seat stadium in Mobile and scratched out a 14-14 tie despite gaining only 195 yards. Back home against the Pennsylvania Mustangs the Comets fell behind 17-0 before reviving on the arm of former North Carolina quarterback Jack Cummings to win 20-17. Wilmington won two more games before a three-game tailspin cost Ferrante his job. The Comets wound up the 1965 season 4-5-1, last in the Northern Division. It mattered not; the NAFL disbanded before the 1966 season.

THE ATLANTIC COAST LEAGUE (1966-67)

Although the NAFL folded, attendance in Wilmington had been an encouraging 19,528 for five home dates. Edward du Pont thus bought into the five-year old Atlantic Coast League on a wave of optimism in 1966.

Once again known as the Clippers, the team started in disarray. The opening game was a fiasco in Atlantic City as Wilmington forced only one punt and was outgained 527 yards to 230 in a 41-14 loss. In the next game, a 27-14 thrashing, the Clippers rushed for only 2 yards. Things were worse off the field. Two Clipper halfbacks were killed in separate auto accidents and a third back broke both legs on his day job, ending his career. Delaware football legend Tex Warrington resigned as coach, saying it just wasn’t any fun.

Another home-grown legend, Ron Waller, took over and the Clippers defense toughened. They battered Rhode Island 48-7 and the loss was so disheartening the franchise folded. The Clippers climbed to 4-7 but their improvement did not catch the fancy of Wilmingtonians. Only 6700 fans turned out for six games.

The Clippers returned to Baynard Stadium in 1967 and even signed a 5-year development pact with the Philadelphia Eagles but its vital signs were weakening. Barely into their second season of play the Clippers had already run through three coaches and three general managers. The original franchise folded but the team continued under league auspices as the Renegades.

After an extended six-week road trip designed to whet expectations of Delaware football fans for their return the Renegades drew 2600 but it was far short of the 4000 expected. After another loss life supports were finally pulled on minor league football in Wilmington.

DELAWARE FOOTBALL PLAYERS

Eddie Michaels. Eddie Michaels, a star lineman at Salesianum and Villanova, was selected by the Chicago Bears in the second round of the National Football League’s first-ever draft in 1936. Michaels went to work for George Halas but only stayed one season before homesickness overtook him and he asked Halas to trade him back East. Halas obliged and shipped Michaels to the Washington Redskins, with whom he defeated his former team in the 1937 NFL Championship game.

Michaels was out of the NFL the next year, back in Delaware playing and coaching for the Wilmington Clippers. He returned to the war-depleted NFL in 1943 (Michaels was classified 4-F because he was hearing impaired) and stayed with the Philadelphia Eagles through 1946. After the war Michaels went to Ottawa in the Canadian Football League where he was a two-time all-CFL performer.

In the 1950s Michaels returned to Villanova to coach, molding among others his son Ed, who was drafted by the Redskins in 1958. Young Ed didn’t stick to the regular season, depriving the Michaels of the chance to be only the second father-son combination to play in the NFL.

Creighton Miller. Cleveland-born Creighton Miller came to Delaware in 1935 and became the greatest high school running back in state history in the first half of this century. After a breathtaking career at A.I. du Pont High School, Miller continued a family legacy by matriculating at Notre Dame. His father Harry had started in the Irish backfield during the Teddy Roosevelt administration, his Uncle Walter had blocked for George Gipp, his Uncle Don was one of the fabled Four Horsemen, his Uncle Ray had backed up Knute Rockne at left end and on and on. As Creighton explained it, “My father didn’t ask me what college I wanted to attend. He told me what time the train was leaving for South Bend.”

Despite his family legacy Miller was not immediately welcomed by Notre Dame coach Frank Leahy. The Delwarean had been diagnosed with high blood pressure and was told not to practice. Leahy considered it laziness but Miller was too good to keep off the field and made the 1941 team as a back-up halfback, gaining 183 yards in 23 carries. When Miller was rejected for military duty because of his medical condition Leahy finally was convinced his backfield star was not shirking practice.

Creighton Miller was one of the most talented Delaware backs to run through a line of scrimmage.

In 1943 Miller became only the second Notre Dame back to rush for more than 900 yards, averaged 6.17 yards per carry and was a unanimous All-American. Leahy also won his first national title. Miller was the first draft pick of the Brooklyn Dodgers but turned down an exorbitant offer of $10,000 to play pro football. Miller already had a career path mapped out. He was a talent scout for the Cleveland Browns and an assistant coach at Yale University, where he was attending law school.

His connection with the Browns led Miller to become the first counsel for the NFL Players Association in 1960. He maintained that position for 11 years until he resigned to become a player agent. In 1976 Miller was elected to the College Football Hall of Fame. At his induction his former Notre Dame coach Frank Leahy summed up his brief football career the best, “Creighton Miller was the best halfback I ever saw.”

Tex Warrington. Caleb Van Warrington was always big. As a 12-year old growing up in Dover he weighed a robust 150 pounds and was shortly thereafter pitching semi-pro baseball for the Dover Chicks. He picked up the nickname “Tex” for his bowlegs, a characteristic of many fine athletes. Warrington attended William & Mary for three years before finishing his collegiate career at an Alabama agricultural school, today known as Auburn, in 1944.

Now a robust 6’2” and 205 pounds the 23-year old Warrington carved out an All-American season at center on offense and linebacker on defense for Auburn. He was drafted by the Boston Yankees but at the time had no desire to try pro football and began coaching at Auburn. The Brooklyn Dodgers eventually lured Warrington into the All-America Conference for three years, including two years as their captain. Warrington then returned to a teaching career that brought him back to Delaware as a program supervisor at Ferris school in 1962.

Carl Elliott. Growing up in Laurel in the 1940s they called Carlton Batt Elliott “Stretch” because that’s what all 6’4” guys were called back then. Elliott could not only reach up for passes but he was a devastating blocker from his split end postion as well. He was an All-Southern end for the Virginia Cavaliers and lined up for the Green Bay Packers when he was 24 years old in 1951. Elliott enjoyed three productive seasons in Green Bay, snaring 60 balls and scoring five touchdowns; he also returned a fumble for a tourchdown.

Leon Dombrowski. An All-State tackle at Salesianum and an all-conference guard at the University of Delaware Leon Dombrowski appeared on his way to becoming the first Blue Hen in the NFL when he played in four exhibition games for the Washington Redskins in 1960. But the 205-pound lineman was released before the season started.

He hooked on with the New York Titans for the debut season of the American Football League. He started the first two games for the Titans, later the Jets, at linebacker but tore up a knee in practice before the third game, which hastened his return to Newark to complete his degree. The Titans refused to honor Dombrowski’s $8,800 contract before settling for half the value. Leon Dombrowski ended his professional career with $2,200 a game.

Tom Hall. Tom Hall was an All-State basketball and football player at Salesianum before moving on to the University of Minnesota where he starred on two Rose Bowl teams. Hall was the holder of seven Golden Gopher receiving records when he was drafted by the Detroit Lions in the 1961 draft.

In Detroit he was used as an occasional kick returner and caught only three passes in two years. Traded to the Minnesota Vikings Hall became a dependable possession receiver for Fran Tarkenton, averaging 20 catches and two touchdowns for the next three years. He was tabbed by the New Orleans Saints in the NFL expansion draft after the 1966 season and played one season as a charter Saint before wrapping up his eight-year NFL career back in Minneapolis.

John Land. John Land grew up in New York City in the 1960s where everyone played basketball. He never played football but idolized superstar running back Jim Brown so when he showed up at Delaware State he decided to try out for the football team, not knowing anything about how to block or catch. He made the team and became a 5’9”, 205-pound blocking back. By his senior year he got the ball enough to gain 600 yards and score seven touchdowns. Several years of semi-professional ball followed in the Atlantic Coast League while he established his business career in

Delaware. Starring for teams like the Harrisburg Capital Colts and Norfolk Neptunes and Pottstown Firebirds Land performed well enough to make the National Pro Minor League Hall of Fame After brief stints with the Philadelphia Eagles and Baltimore Colts Land signed on with the Philadelphia Bell of the World Football League in 1974 and rushed for 1,136 yards and caught passes for 646 more. Of the field he picked up a doctorate and served 19 years as a trustee at Delaware State.

Kevin Reilly. Kevin Reilly had an opportunity to watch some of football’s best linebackers up close - from behind them on the depth charts. After a successful career as a two-way end on the undefeated 1968-69 Salesianum football team Reilly went on to make All-East at Villanova as a linebacker. He was drafted by the Super Bowl champion Miami Dolphins in 1973 where he tried to make the team as a back-up to Nick Buoniconti before being released in training camp.

He hooked on with the Philadelphia Eagles where he subbed for All-Pro Bill Bergey for two seasons. Slowed by injuries, Reilly was waived by the Eagles and caught on with New England for one final season, dueling with George Webster and Steve Zabel for playing time. Three years of special teams play wore down Reilly’s body and forced him out of football. The highlight of his NFL career came on a 90-yard interception he brought back for a touchdown. That, and watching some excellent linebacking play.

Grant Guthrie. Grant Guthrie was the best kicker ever to come out of Delaware. He set records at Claymont High School and Florida State University before kicking for the Buffalo Bills in 1970 and 1971. His NFL career was brief but he joined the Jacksonville Sharks of the new World Football League in 1974. He set a league record with four field goals in one game but after going six games without a paycheck he left the Sharks, who folded. Guthrie then kicked game-winning field goals in the final two games for the Birmingham Americans but again they were free kicks with no paychecks forthcoming. On the field Guthrie converted 18 of 24 field goal attempts in 1974, his best kicking season ever, but the experience left him financially strapped, souring his last year in professional football.

Gary Hayman. Playing at Newark High School Gary Hayman won 33 straight games. He expected much of the same when he enrolled at Penn State with Joe Paterno. But he lost two seasons to injury and a third clearing himself of a wrongful rape charge before finally returning to the Nittany Lions in the fall of 1972. The next year Hayman was back to his winning ways. Penn State completed a perfect 12-0 season with a win over Louisiana State in the Orange Bowl.

Hayman led the nation in punt returns that year for Penn State. He also hauled in 30 passes for 525 yards. Against Maryland he returned the opening kickoff 98 yards for a touchdown. Blessed more with great acceleration than blinding speed Hayman was picked by the Buffalo Bills in the 1974 NFL draft. Converted to a running back Hayman backed up O.J. Simpson and returned kicks but a broken leg slowed his progress. After two years with the Bills there was a short stay with the Seattle Seahawks before retirement.

Conway Hayman. It took more than a half-century before Dennis Johnson became the first University of Delaware player to line up for a down in the National Football League. And when Conway Hayman became the second he had to be as surprised as anyone.

Drafted in the sixth round in 1971, the Little All-America from Newark High was among the best pro prospects to ever play for the Blue Hens. But after four years of sweating through NFL tryout camps in Washington, New England and Los Angeles Conway Hayman was back in Delaware carving out a career in the Wilmington Planning Department. But one more training camp invitation came in 1975. And when the season opened Hayman was a regular on the Houston Oiler offensive line. For six years Hayman remained a stalwart for one of the best Oiler teams ever; twice Hayman played in the AFC Championship game. After a back injury sent Hayman to the sidelines in 1981 he returned to football as a coach for Prairie View A & M University in Texas, compiling a 5-31-1 mark in little over three years in a difficult situation.

Joe Campbell. Like Randy White before him Joe Campbell never made the Delaware All- State football team. Campbell didn’t even rate Honorable Mention in his senior year in 1972 when he anchored the state champion Salesianum defensive line. College recruiters ignored Campbell as well. He followed White to the University of Maryland, almost as an afterthought on the part of the Terrapins.

Despite slipping quietly onto campus the 6’6”, 250-pound defensive end lettered all four years with Maryland and made several All-American teams in his senior year.He played in bowl games all four years and was tabbed by the New Orleans Saints in the first round of the 1977 draft, the seventh player taken overall.

Campbell’s inexorable climb to greatness stalled in New Orleans. Despite landing on one of the least talented teams in the NFL Campbell was unable to win a steady job. He was benched as a defensive end and was unable to make the transition to linebacker. Finally, in the middle of the 1980 season Campbell was traded from the 0-6 Saints to an Oakland Raiders team on their way to the Super Bowl.

Campbell earned a Super Bowl ring as a special teams player in the Raiders 27-10 dismantling of the Philadelphia Eagles in Super Bowl XV. But Campbell’s career was on the wane. After being waived by the Raiders he played half a season with lowly Tampa Bay before winding up his career in the USFL with the New York Generals.

Tim Wilson. Tim Wilson made his NFL reputation as a blocking back, clearing holes for the likes of all-time great Earl Campbell. Ironically Wilson never blocked a single man, by his reckoning, during his three years of football at De La Warr High School. At the University of Maryland Wilson’s blocking technique was so poor he was moved to offensive end. Eventually Wilson was returned to the backfield and became a ferocious blocker for future NFL runners like Louis Carter, Rickie Jennings and Steve Atkins. Wilson could move the ball as well. He gained 610 yards his senior year at College Park and led the team with 42 points.

Like Randy White, a non-Delaware All-State player who went on to a professional career Wilson was drafted into the Houston Oiler backfield in the third round of the 1977 NFL draft. In his rookie year he bulled for 431 yards on 129 carries but his notoriety came as a bruising blocker. Wilson was a prototype fullback in an offense built around a featured tailback.

Anthony Anderson. Anthony Anderson shattered Delaware state records bursting out of the McKean backfield in the mid-1970s and starred for the Temple Owls as well. He was selected by the Pittsburgh Steelers in the annual NFL draft and saw spotty action in 1979, returning 13 kickoffs. Although he didn’t get in the game Anderson became the second Delawarean to claim a Super Bowl ring as a member of the victorious Steelers against the Los Angeles Rams. Dropped by the Steelers, Anderson spent part of the 1980 season with the Atlanta Falcons before resurfacing as a dependable performer in the United States Football League with the Baltimore Stars until his retirement in 1985.

Mike Meade. Mike Meade barrelled through enough defenders from the Dover Senators backfield to rush for more than 2,000 yards in both 1976 and 1977, contributing to a state championship in his senior year. In Joe Paterno’s backfield at Penn State Meade job was mostly to clear space for College Hall of Famer Curt Warner. Meade was selected in the 5th round of the 1982 draft by the Green Bay Packers and started seven games the following year. He gained 201 yards and proved useful out of the backfield catching 16 passes for 110 more. Still, Meade was traded to Detroit where he saw little action with the Lions before leaving the NFL with one career touchdown.

Frank Cephous. At St. Mark’s High School Cephous was a state high jump champion and a member of the Spartans 1978 football championship team. He went west and played three years, rushing for 1066 yards and gaining 300 yards receiving. Cephous spent one year with the New York Giants in 1984 returning kickoffs and gaining two yards from scrimmage on three carries.

Dan Reeder. Christiana High School product Dan Reeder wound up in the University of Delware backfield after a stop at Boston College and was picked by the Los Angeles Raiders in the 5th round of the 1985 draft. He didn’t make the silver-and-black roster but caught on with the Pittsburgh Steelers as a back-up for two years getting eight carries and gaining 28 yards.

Clarence Bailey. Clarence Bailey graduated from Milford Senior High School in 1982 and attended Wesley College before moving on to play for the Hampton University Pirates. Bailey played two years in Virginia, leading the Pirates in scoring in 1984. He averaged 19.1 yards per punt return - still a school record. He played semi-pro ball with theChesapeake Bay Neptunes in Norfolk and signed as a free agent with Miami Dolphins in 1987, getting into three games for Don Shula and gaining 55 yards on just ten carries.

Lovett Purnell. Lovett Purnell was a three-sport star at Seaford High School, drafted by baseball’s Chicago White Sox in the 54th round and second only to Delino DeShields in points scored on the Blue Jay basketball court. He chose to pursue football and caught 78 passes in two years as a West Virginia Mountaineer tight end. He was drafted by Bill Parcells and the New England Patriots in the 7th round of the 1996 draft and started every game for two years in 1997 and 1998. Targeted sparingly by Drew Bledsoe, Purnell caught only 17 passes but five were for touchdowns; he also started for the Patriots in the 1997 Super Bowl.

Jamie Duncan. Jamie Duncan was a two-time Delaware high school player of the year at linebacker for Christiana High School and the gridiron honors kept coming after he enrolled at Vanderbilt University: twice an All-American and the 1997 Southeastern Conference Defensive Player of the Year. The Tampa Bay Buccaneers snapped Duncan up in the third round and he started six games at middle linebacker in his rookie year. By his third year he was the everyday middle backer, intercepting four passes and taking one back 31 yards for a touchdown. Duncan’s career ended after seven seasons and he pursued diverse business interests inlcuding a hair styling salon in his home state.

Jim Bundren. A Michigan native, Jim Bundren became an All-State performer at A. I. du Pont High School. After a year at Valley Forge Military Academy he was recruited by Clemson University and started a record 47 games for the Tigers in his four-year career. The Miami Dolphins picked Bundren in the 7th round of the 1998 NFL Draft but be did not surface until the following year with Cleveland Browns and started ten games in a two-year professional career.

Kwame Harris. Kwame Harris came to Newark from Jamaica when he was ten years old - his father opened a successful Jamaican-fusion restaurant. He favored playing the violin and piano but at over 300 pounds with speed and quickness the football field beckoned. When his career at Newark High School ended the family said the number of recruiting letters from courting colleges filled two 40-gallon trash bags. He chose Stanford University as a music major. Harris was the second-ranked offensive tackle in the 2003 NFL Draft and the San Francisco 49ers made him the 26th overall pick. Harris started 37 straight games with the 49ers but never lived up to his potential in six NFL seasons. After leaving football he came out as one of the first ex-NFL players to identify as gay. Kwame’s younger borther Orien also saw spot duty in the NFL for three years.

Montell Owens. At Concord High School Montell Owens was a triple threat as a student (National Honor Society), a jazz musician (toured Europe with American Music Abroad) and on the football field where he rushed for 1,100 yards and 20 touchdowns. Owens played his college football at the University of Maine and signed on with the Jacksonville Jaguars as an undrafted free agent in 2006. He has developed into a special teams specialist, establishing the franchise record for most career special teams tackles with 118. He only got 56 rushing attempts in his nine-year NFL career but scored three touchdowns. Twice he was named to the Pro Bowl as a special teams player and in 2011 scored twice in the game, once on a fumble recovery and once on a pass reception.

Jeff Otah. Nigerian-born Jeff Otah came to Delaware via the Bronx at the age of 13. He played only one season at William Penn High School before two years of seasoning at Valley Forge Military Academy prepared the 340-pound offensive lineman for the rigors of the Big East at the University of Pittsburgh in 2006. Two years later the Carolina Panthers drafted Otah in the first round with the 19th pick. He became an immediate starter for the Panthers but after his first two years his career was curtailed by injury.

Duron Harmon. Both of Duron Harmon’s parents were graduates of Delaware State but after leading hometown Caesar Rodney High School to a state championship in 2008 the Magnolia native spurned the hometown school and went to Rutgers University instead. He had rushed for 1,126 yards for the Riders but was also the Delaware Defensive Player of the Year. Harmon concentrated on the defensive side of the ball with the Scarlet Knights. He had 129 tackles and six interceptions in his four years in East Brunswick and was taken by the New England Patriots in the third round of the 2013 NFL draft. For Bill Belichick the versatile defensive back intercepted six balls in three years, including a key pick of Joe Flacco late in the 2014 divisional playoffs to seal a game against Baltimore. A few weeks later Harmon earned a Super Bowl ring against the Seattle Seahawks.

Justin Perillo. At tiny private school Tatnall Justin Perillo figured he would be wrapping up his football career when the Hornets completed the 2009 season. He had no college recruting interest. If anything the Delaware Basketball Player ofthe Year figured he had a future on the hardwood. But the University of Maine saw some Tatnall School footage and offered him a scholarship. In four years in Orono as a tight end Perillo caught 128 balls for 1,318 yards and 15 touchdowns. There were no nibbles from the pros but Perillo signed with the Green Bay Packers in 2014 and made the practice squad. In 2015he was called into nine games and made 11 catches for 102 yards and a touchdown.

A FOOTBALL LIFE

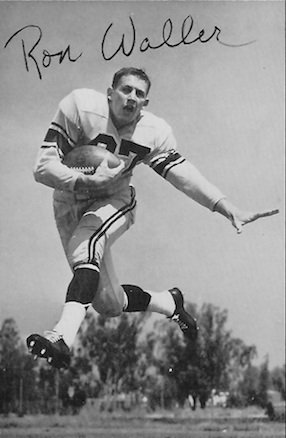

If Delaware ever had a mythical “Golden Boy” it was Ron Waller. An all-time high school scoring champ, an All-American running back, an All-Pro in his rookie year, married to a millionaire actress-heiress and living in southern California. What Delaware boy growing up in the 1950s didn’t want to be Ron Waller?

Waller first rose to prominence on the playing fields of lower Delaware in the 1940s. By the time he graduated from Laurel High School he had hoarded 12 letters - three each in basketball, football, track and baseball. It was football, however, where Waller made his lasting fame. Ron Waller was one of the most gifted halfbacks ever to glide across a Delaware gridiron. In 1950 alone he scored a Chamberlainesque 213 points with 30 touchdowns and 33 extra points - and he often sat out the second half of games. His selection as Delaware Athlete of the Year was a no-brainer.

At the University of Maryland Waller developed into an All-Conference back averaging nine yards per carry. He also was one of the top punt returners in the nation. The Washington Redskins drafted him in the second round of the 1955 draft but traded him immediately to the Los Angeles Rams where Waller came under the tutelage of the innovative offensive tactician Sid Gillman.

In the last 1955 exhibition game Waller grabbed nine passes for 184 yards and clinched a starting backfield position in his rookie year. Taking hand-offs from Norm Van Brocklin, Waller raced to 716 yards, many on electrifying runs, to finish fourth in the league in rushing. He also averaged over 27 yards per kickoff return and was named to the Pro Bowl and UPI All-Pro teams.

His off-season was no less memorable. After a public courtship Waller married heiress and actress Marjorie Merriwether Post of the Post Cereal fortune, one of the most substantial in America. Their wedding was the highlight of the 1955 social season in Washington DC.

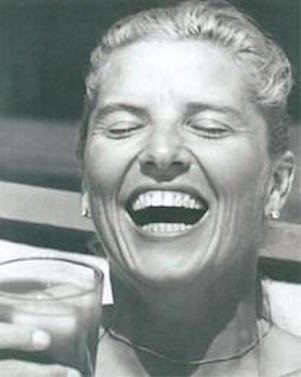

Ron Waller's skill at halfback led to one of Delaware's more high profile marriages - to cereal heiress Marjorie Merriwether Post.

In 1956 Waller was slowed by a shoulder injury but still gained 543 yards on an eye-popping 6.65 yards per rush and made second team All-Pro. A rib injury landed him in a backup role in 1957 and he ran for only 292 yards, still leading the league in yards per carry. But the injuries exacted their toll. The next year he was released by the Rams.

By now Waller was firmly entrenched in the California scene. He operated a plush bowling alley and several bar-restaurants for the California sports crowd. He fronted an exclusive catering service to the stars and raced thoroughbreds. And of course there was Hollywood. Waller produced some television shows and acted a bit, too. He did a turn on 77 Sunset Strip and in the movies had a speaking part opposite Marlon Brando and David Niven in Bedtime Story.

Ron Waller was one of football's most electrifying performers before being slowed by injuries.

As his football career melted away so too did his marriage. By 1960 it was over. Waller tried his hand at promoting fights but was never able to completely extricate himself from football’s grip. He began a fascinating odyssey that would touch on virtually every professional football league in the latter part of the 20th century. Waller launched a comeback in 1960 under his old coach Gilliam with the San Diego Chargers in the American Football League. There was no football left in his body and he eventually turned to coaching. Waller resurfaced in Delaware in 1966 as a social worker and backfield coach for the Wilmington Clippers of the Atlantic Coast League. He was shortly made head coach and nursed the team, totally lacking in resources and support, through another year before it folded.

He went on to successful minor league stints with the Harrisburg Capitols, Pottstown Firebirds and Norfolk Neptunes before rejoining the NFL with the San Diego Chargers in 1973 as a special teams coach. When head coach Harland Svare was ousted in near-mutiny at mid-season Waller was elevated to head man and coaxed one win in the final six games out of the rebellion. He headed to Europe and the Intercontinental Football League saying the Charger’s biggest need was a quarterback as a young future Hall-of-Famer Dan Fouts was buried on his bench.

By 1974 he was back as head coach of the Philadelphia Bell in the World Football League, one of the worst professional leagues ever devised. Waller guided the Bell through one season before he resigned in July 1975 with the tattered league in its final death throes. Waller, who once said philosophically, “I just seem to gravitate toward difficult situations,” returned to California as coach and part-owner of the Southern California Rhinos of the California League.

When the United States Football League happened along in the mid-Eighties Waller was in the front office of the Kansas City Chiefs. He signed on with the USFL as Offensive Co-ordinator for the Chicago Blitz but when that league folded he turned down further NFL offers and returned to Delaware where he put his natural charm and optimism to work in a new field - politics.

SLOW AND STEADY

Slow. It’s a word that football people always seemed to get around mentioning when they talked about Steve Watson. Which was not a particularly encouraging adjective when describing a split end. Slow. It’s a word that describes how it took football people to appreciate Steve Watson’s talents.

Growing up in Baltimore Watson was a superb games player. Not the least of his skills was skeet shooting, in which he was a national champion. Entering St. Mark’s High School in 1972, Watson was an aspiring running back but was switched to split end where he started on back-to-back Spartan state champion teams in 1973 and 1974.

After high school only Virginia and Temple came courting the All-State end. Temple was the more ardent suitor and Watson joined the Owls where he hauled in 98 passes in four years, good for 1629 yards. Still, he was ignored on draft day, labeled by NFL scouts as “too slow.” The 6’4”, 195-pounder doggedly pursued his NFL dream and caught on with the Denver Broncos as a free agent in 1979. In two years of mostly special teams work Watson caught only 12 passes.

He got an opportunity to start early in 1981 when an injury felled leading receiver Rick Upchurch. In his first two games Watson grabbed 15 receptions for 321 yards. He scored five touchdowns of 29, 18, 48, 93 and 22 yards. He would go on to snare 60 balls and led the NFL in touchdowns with 13. His 1244 yards stretched all the way to the Pro Bowl in Hawaii.

Over the next five years only one NFL receiver would pile up more receiving yards than “slow” Steve Watson. From 1983 to 1986 he started 64 straight games. He was roundly praised for his exceptional hands, precise routes and the ability to make the “tough catch.” Watson was the Broncos MVP on offense in 1981, 1983 and 1984 and in 1986 he became the fourth Delaware high schooler to appear in a Super Bowl.

Always one of the most popular Broncos, Watson extended his career a couple more seasons. When he was released an explanation given was that the Broncos were “heading in another offensive direction” - they were going with faster receivers.

Not necessarily better ones. Watson finished his career with 353 receptions for 6,112 yards and caught 21 more balls in the postseason. For such a slow guy his career average of 17.3 yards per catch is the 44th best in league history.

UNIVERSITY OF DELAWARE FOOTBALL COACHES

William McAvoy. After relying on a series of part-timers to lead its football team Delaware College made a commitment to athletics in 1908 by hiring its first permanent coach. The man tabbed for the job was William McAvoy, an All-American running back from Lafayette College. Drafted by the Pittsburgh Pirates as a baseball player, McAvoy had spent the summer patrolling the outer pastures for Rochester of the Eastern League, finishing 4th in the league in batting.

“Coach” at Delaware College was not a position assumed lightly. In addition to his duties with the football squad McAvoy guided the Blue Hen athletes in baseball, basketball and track. Under McAvoy Delaware did not magically transform into a football power. He simply did not have the material; enrollment at the college seldom topped 200 and his teams never averaged more than 165 pounds per man. Delaware officials went so far as to consider replacing football with soccer in 1913, sending McAvoy out to scout several soccer games for his evaluation.

A McAvoy team was always in shape and never quit. He operated with no funds and scholastic rules were strictly adhered to. Still Delaware enjoyed many big wins under the energetic McAvoy. He was regarded as a good motivator and popular in the coaching fraternity, able to tap the minds of many of the greatest football strategists in the country.

Bill McAvoy helped save football at the University of Delaware in 1913.

McAvoy led the Blue Hens until 1917 when he enlisted in Officers Training School and shipped overseas to serve as a lieutenant in World War I. After the war he returned to the sidelines with the Drexel Dragons but when his old job at Delaware opened in 1922 he was eagerly courted by his friends in Newark.

In the final game of the 1923 season McAvoy engineered one of the great upsets of the football season by drubbing national power Dickinson 21-0. As the Delaware freshmen and sophomores gathered wood, boxes and barrels for a celebratory bonfire in front of Wolf Hall, McAvoy declared himself “the happiest man in the United States.”

In 1925 William McAvoy moved on to the University of Vermont. In his wake he left behind a legacy for athletic success on and off the gridiron. The annual interscholastic track and field meet McAvoy started in 1913, for instance, was drawing over 30 schools. From the point of his departure the University of Delaware would be forced to create an athletic budget to maintain the level of achievement initiated by Coach McAvoy.

Bill Murray. In 1940 Bob Carpenter, Jr. spearheaded a “new regime” at the University of Delaware, dedicated to excellence in competitive sports. The man he found to guide the fortunes of the football program was directing athletics at Winston-Salem College in Rocky Mount, North Carolina. Prior to that he was teaching school in the Blue Ridge Mountains. The Journal Every Evening welcomed the unheralded Bill Murray as “another in a long line of those who have made the journey to Newark in the past 12 years.”

It would not be long before the former All-American halfback from Duke would excuse himself from that undistinguished procession.

Murray lost his first three games as he waited for his new charges to master the intricacies of his double-wing offensive system. Publicly he bemoaned his teams’ defense and kicking. The nadir of his debut campaign came on Homecoming when Delaware was whited-out 25-0 by Ursinus in the snow. But the following week, in the first University of Delaware game played in Wilmington since 1922, the Blue Hens upended a powerful Pennsylvania Military College team 14-7 in a huge upset. Delaware would not lose for another 31 games.

As Murray began winning he bred a new sports follower in Delaware - the spoiled fan. Well-oiled routs of overmatched teams spawned cries for a tougher schedule. Less than decisive victories in the streak led to carping from disgruntled alumni about underfed wins. This from fans of a team that heretofore had notched 15 winning seasons in the past 50 years!

Bill Murray started a run of over 60 years of Hall of Fame-level coaching at the University of Delaware.

All the while Murray was on the defensive regarding the caliber of his football player. Most were unknown in high school; all had to come from the top half of his class. Delaware was still a small school with an enrollment of 1700 and no national reputation. Still Murray went on winning.

World War II shut down football at the University of Delaware but Murray welcomed an unprecedented 90 try-outs to spring practice in 1946. This suited Murray who was a strong advocate of single platoon football. He railed against the coming of football specialists on the offense and defense as divisive to team spirit. A large squad enabled Murray to shuffle as many as 40 players in and out of a game to keep his troops fresh.

With a team comprised entirely of returning servicemen Murray enjoyed his greatest year in 1946. More than 10,000 fans welcomed football back to the University of Delaware in Wilmington Park as the Blue Hens wiped out the cadets of PMC 25-0. After a 52-0 Homecoming win over Drexel, Delaware showed up in the Associated Press national rankings at 27th.

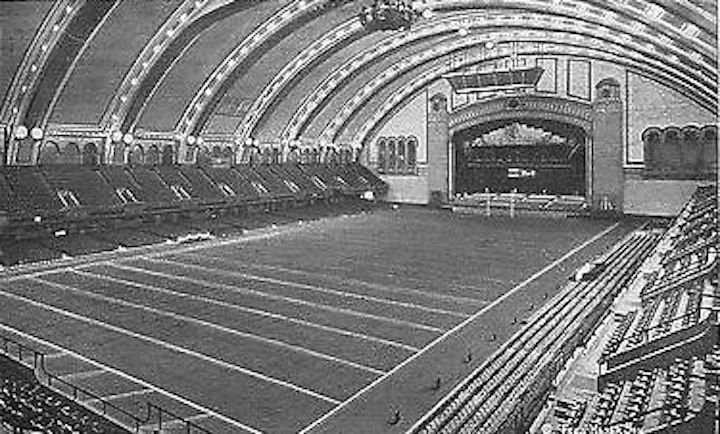

As the Hens reached 8-0 they climbed to 16th in the polls and Murray prepared for #19 Muhlenberg in the only battle of two Top 20 teams ever staged in Delaware. The capacity of Wilmington Park was increased from 10,000 to 14,000 for the “Battle of the Little Titans.” Wilmington was the football capital of America on this day with the pressbox stuffed with national writers. There was talk of the winner being in line for a Cotton or Orange Bowl bid.

The Hens built a 13-0 lead and ground out a 20-12 win. They out-gained the Mules 330 to 185 in taking one of the greatest games ever played in Delaware. The next week the University of Delaware moved to 15th in the AP poll, ahead of such powerhouse elevens as USC, Texas and Oklahoma. They even pulled two first place votes as the best college football team in the country.

Murray accepted a bid to play in the Cigar Bowl in Tampa on January 1, one of 21 New Year’s Day bowls that year, including the Cattle, the Vulcan, the Coconut and the Will Rogers Bowl. Delaware was established as a two-touchdown favorite over Rollins College of Atlanta and their 21-7 victory was one of the most impressive of the day. Navy pilot Paul Hart rushed for 113 yards and one touchdown and passed for two more to complete the scoring.

Delaware finished 19th in the 1946 final AP poll, with one writer still clinging to the belief that the Blue Hens were the top football team in the country. During the regular season the Delaware offense, utilizing a double-wing attack, outscored opponents at a 337-38 clip. A host of individual records were set as well. Gerald “Doc” Doherty set a single game rushing mark with 220 yards - on only six carries. His runs were of 83, 63, 32, 18, 13 and 11 yards. He averaged more than 12 yards per carry in 1946.

The winning skein streaked into 1947 until a Gator Bowl-bound University of Maryland derailed the Blue Hens 43-19 before a record College Park crowd of 16,460. It would be the biggest crowd to watch the University of Delaware play football until Delaware Stadium would expand two decades later.

As his success in Newark grew bigger schools clamored for Murray’s services. He explored the coaching job at Vanderbilt and the Athletic Director’s position at the University of Minnesota before returning to Duke in 1951 trailing behind his worst season ever at 2-5-1 in 1950. He finished his tenure at Delaware 47-16-2 in eight years.

Murray rebuilt his alma mater into a premier powerhouse before becoming executive director of the American Football Coaches Association. At Duke, “Smiling Bill,” as Murray was known for a slight grin built into his facial expression, went 93-51-9. In 1974, in recognition for his work at Delaware and Duke, Bill Murray was enshrined in the National Football Foundation Hall of Fame.

Tubby Raymond. There was a time in Tubby Raymond’s career when he was in danger of becoming known as a baseball coach, not a football coach. It was true that after nine years at the University of Delaware Raymond was the winningest baseball coach in the school’s history with 141 wins and only 56 losses. And it was true that he loved baseball, but Tubby Raymond was a football man. And as a well-thought-of backfield coach for the Blue Hens charting his future Raymond found potential employers thinking of his baseball achievements. So he gave up baseball.

Harold Rupert Raymond was born, raised and schooled in Michigan. He was tagged with the appellation “Tubby” as a butterball of a five-year old and was never able to fight his way out of it, although he tried. The young Raymond stopped growing at 5’8” and 167 pounds but he developed into a scrappy two-way guard in football. He was also an outstanding baseball catcher.

After a stint in the aviation cadet program during World War II Raymond enrolled at the University of Michigan. He worked his way onto the elite Wolverine football team which would win the 1947 national title but he never lettered. He was, however, a three-year starter on the baseball team and Tubby Raymond, football guy, even had an abbreviated two-year career buried deep in the New York Yankee organization.

On the recommendation of Fritz Crisler, his football coach at Michigan, Raymond got a job coaching Ann Arbor University High School in his senior year. Two years later he was in the Michigan-to-Maine-to Delaware pipeline laid by Dave Nelson. He spent two years as line coach for the Black Bears before joining Nelson as a backfield coach at Delaware. As the leading disciple of Nelson’s Winged-T offense it was not long before other schools came calling on Raymond. Iowa, Kentucky, Louisiana State, California and Oklahoma all dangled assistant coaching positions in front of Raymond. But he had long ago decided not to forsake Delaware for anything less than a head coaching job.

That opportunity arrived in 1966 with an offer to take over the football program at the University of Connecticut, a school similar in philosophy to that which Raymond loved at Delaware. Faced with losing Raymond and saddled with more and more non-coaching distractions it was the logical time for Nelson to step aside.

Under Raymond the Blue Hens climbed to even greater prominence than that achieved by Murray and Nelson. He coached for 36 years until stepping down in 2002 at the age of 75 with exactly 300 wins, measured against 119 losses and three ties. Raymond has amassed a helmetful of coaching awards and three national championships: in the polls in 1971 and 1972 (Raymond’s only undefeated team at 10-0) and on the field in 1979. After moving to NCAA Division I-AA in 1980 Raymond took the Blue Hens to the playoffs 11 times, losing three times in the national semi-finals and dropping the national championship game to Eastern Kentucky in 1982, 17-14.

The old baseball coach (there were eventually 178 of those before he hung up the spikes in 1964 and three NCAA Tournament appearances) followed Murray and Nelson into the College Football Hall of Fame in 2003. His name was added to the field at Delaware Stadium.

One thing that did not come to an end with Raymond’s retirement was his tradition of painting every starter in acrylics in his senior season. Raymond had painted portraits growing up and Nelson encouraged his assistants to sketch the players as a way of building team bonds. After putting down his whistle and picking up his brush, Raymond began fielding commissions in his studio and painting everyone from university officials to the neighbor’s kids.

UNIVERSITY OF DELAWARE QUARTERBACKS

Don Miller. When Dave Nelson arrived at the University of Delaware in 1951 he was greeted by four quarterback candidates at his first practice. Nelson selected from this quartet as his quarterback a 170-pound freshman from Prospect Park, Pennsylvania who had come to Delaware mostly on his basketball ability. Don Miller would go on to start every one of the 32 games over the next four years.

Miller’s completed only 58 of 123 in his rookie year but 12 tosses went for touchdowns. A bad shoulder hindered his progress in his sophomore year but Miller returned in 1953 to make third team Little All-America. In the 1953 season finale against Bucknell Miller was 14-20 for 278 yards and four touchdowns, missing a fifth when his receiver tumbled out of bounds inside the one-yard line.

Don Miller led Delaware to a win in the 1954 Refrigerator Bowl.

Despite his talented arm Miller’s greatest assets were his coachability and ball handling, where #11 was the focal point in Nelson’s intricate Winged-T offense. Miller had his greatest year as a senior for the 1954 Blue Hens who lost only two games, each by a single point and romped to a win in the Refrigerator Bowl. Miller was named first team Little All-America quarterback and his 36th career touchdown pass broke the Eastern College record - on a running team.Miller was not drafted by the NFL but he had already planned on a coaching career. He started as coach of Newark High School in 1955 and went 22-3 in his first three years, losing in-state only to William Penn by one point. In 1958 Miller’s Yellowjackets won all five Blue Hen Conference games to win the state’s first conference championship. After this final Delaware triumph Miller left the state for Amherst College, where he continued his now deep-rooted success.

Tom DiMuzio. Tom DiMuzio was Tubby Raymond’s first great quarterback and maybe his best. A converted halfback, DiMuzio could run as well as he could pass. And he set 14 school records passing. As a senior in 1969 DiMuzio was a second team Little All-American - behind a modest talent named Terry Bradshaw. Any other year DiMuzio’s grit and daring would certainly have earned him first-team status.

DiMuzio led Delaware through an uncharacteristically horrid season in his sophomore year in 1967. The Blue Hens won only twice in nine tries as DiMuzio threw just 11 times while carrying on 81 plays. The next year Delaware went 8-3 as DiMuzio took to the air. The season climaxed in Atlantic City’s Boardwalk Bowl as DiMuzio threw a 9-yard scoring pass in the waning seconds to upend Indiana of Pennsylvania 31-24. It was his third touchdown strike of the day as he hit on 15 of 22 tosses for 264 yards.

In his senior year DiMuzio established a University of Delaware standard for touchdown passes in a season with 24, including a record five against Lehigh. In that game DiMuzio connected on 22 passes for 369 yards. Once again he led Delaware to a win in the Boardwalk Bowl. Although named the Most Valuable Player in the Middle Atlantic Conference, in addition to his other awards, the pros did not come calling for DiMuzio, who began his business career after leaving Newark.

Jeff Komlo. There was never any indication that Jeff Komlo would be one of the all-time Delaware quarterbacks until he actually was. A former Maryland prep star, Komlo arrived in Newark unheralded and after an undistinguished freshman year he began the 1976 season as a fourth string signal caller. Following several ineffective performances by his competition Komlo was elevated to starter, a position he would never relinquish.

Early in his career Komlo was noted mostly for his leadership skills and proclivity for the big play. He hit fewer than 50% of his passes in his sophomore and junior seasons. By his senior season the 6’2”, 210-pound Komlo was a deft handler of the Wing-T at the controls of a team he would lead to the Division II national championship game.

Komlo was at his best in these 1978 playoffs, tossing for 689 yards in three games and going 21 for 35 in the Blue Hens’ narrow loss to Eastern Illinois in the final game. For his career Komlo was 23-9-2 and broke every season and career passing mark at Delaware. Yet, in tribute to his consistency, he set not one single-game record.

Running a sophisticated passing attack and possessing an uncanny ability to find secondary receivers Komlo was named Delaware’s second Little All-America quarterback. He went in the ninth round of the NFL draft to the Detroit Lions and made the team as a third-string quarterback. When injuries knocked out Gary Danielson and Joe Reed, Komlo became an NFL starter in his rookie season, throwing for 2238 yards and 11 touchdowns but he was plagued by 23 interceptions.

When the regulars returned the next fall Komlo was back on the bench. He threw only 69 more passes in his NFL career before winding down with the Tampa Bay Bucaneers in 1983.

Scott Brunner. As a two-year back-up to All-American Jeff Komlo, Scott Brunner enjoyed only one year as a Blue Hen starter. But that one season was the most memorable in Delaware football history. And it cemented Brunner’s place in the pantheon of Delaware quarterbacks.

In his long-awaited 1979 debut Brunner completed 12 of 18 passes for 229 yards in a 34-14 opening day romp over Rhode Island. From there it was a series of highlights for Brunner and the #1 ranked Hens. A 44-yard touchdown pass with 2:28 left to Jay Hooks dispatched 1-AA Villanova 21-20; five touchdown passes tied Tom DiMuzio’s record in a 47-19 win over C.W. Post; directing 602 Delaware yards against William & Mary and earning ECAC Player of the Week honors; a season-high 285 yards while upending Colgate 24-16; and, of course, the Youngstown game.

The Delaware-Youngstown State game will forever live in many a University of Delaware football fan as the greatest game ever played. Both teams were tied for the #1 Division II ranking when they tangled at Falcon Stadium in Youngstown, Ohio. The Penguins took advantage of several Delaware miscues to seemingly bury the Hens 31-7 at halftime in front of 13,142 enthusiastic partisans. But it was Youngstown making the mistakes in the second half and Brunner engineered six touchdown drives, the last starting with 2:19 to go, as Delaware outlasted the Penguins 51-45.

It was no surprise the two teams met again for the Division II Championship, this time in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Once again it was Brunner leading the Hens past an 21-7 deficit to win the national title, 38-21. Brunner finished the year with 2401 passing yards and 24 touchdown passes and was named first-team Little All-American. At 6’5” with a strong arm Brunner looked like a prototype NFL quarterback and indeed he was chosen by the New York Giants in the 6th round of the NFL draft.

At New York Brunner battled Phil Simms for several years before losing out to the future Hall-of-Famer. In his first start as a Giant in 1980 Brunner hurled touchdowns of 48 and 50 yards in a 27-21 Giant win. In part-time duty he threw for 978 yards in 1981 and in 1982 Brunner took every center snap for the Giants and threw for 2017 yards and 10 touchdowns.

The next year Brunner was again a starter and established career highs in completions with 190 and yards with 2516. But he also threw a dangerous 22 interceptions. He missed the 1984 season with a knee injury ceding the quarterback job to Simms. He tried to comeback in 1985 with the St. Louis Cardinals but his effective days as an NFL quarterback were over.

Rich Gannon. “He is the most dominant player in a football game I’ver ever seen,” Tubby Raymond once said of Rich Gannon. He was certainly the most productive three-year quarterback in Delaware history, accounting for 7436 yards of total offense. The fastest of the great Delaware quarterbacks, Gannon became the first to rush for 1000 career yards from under center. And the former St. Joe’s Prep star from Philadelphia averaged 37.2 yards per kick as a punter. All told Rich Gannon took 21 Blue Hen records to the NFL when he was drafted in the 4th round, the highest University of Delaware selection ever at the time, by the New England Patriots.

With all his talent Gannon was not able to take his team to the NCAA playoffs until his senior year in 1986, despite a 15-7 record his first two years. That year, after a 9-3 regular season Delaware was demolished 55-14 in the first round of the 1-AA playoffs. It was an inglorious curtain to be drawn on Gannon who threw for 5927 yards and ran for another 1509 at Delaware.

The Patriots eyed Gannon as an offensive end or defensive back but he only planned to play quarterback so he was shipped to the Minnesota Vikings where he played several years, never quite able to win a job permanently under center. Improbably that began to change in his early thirties when Gannon went to the Kansas City Chiefs as a back-up signal caller. He performed well enough to ink a free agent contract with the Oakland Raiders in 1999 and beginning at the age of 34 started every game for the silver-and-black for the next four years.

At the age of 37 Gannon threw for 4,689 yards, won the league MVP and led the Raiders to the Super Bowl against the Tampa Bay Buccaneers. Jon Gruden, who had brought Gannon to Oakland was now the coach of Tampa Bay, and his defense stymied Gannon, intercepting five passes and returning three for touchdowns in a 48-21 Buccaneer win. Injuries and age brought the curtain down on Gannon’s career in 2004, after 17 years in 2004, 29,000 yards passing and 180 touchdown passes.

Andy Hall. Andy Hall was both a throwback to the Blue Hen dual threat running and passing quarterback and a pioneer in being a transferring Division I quarterback to the Delware backfield. Hall was a big-armed high school star in Cheraw, South Carolina who started his career at Georgia Tech. After two years in the Atlantic Coast Conference where he threw only 19 passes, Hall traded the Atlanta campus for Newark.

He started in 2002 and 2003 and set a school record with 28 completions in a game against Massachusetts. He also broke the school record with 234 completions and 3,474 total yards in a season. After leading the Blue Hens to the 2003 NCAA Division I-AA championship, Hall was named the Outstanding Senior Male Athlete of the Year at the University of Delaware

The NFL came calling for Hall in the sixth round of the 2004 NFL Draft and he spent time on the Philadelphia Eagles practice squad before being assigned to Rhein Fire of the NFL Europe league. Hall drifted into the Arena Football League where he took the Austin Wranglers to the playoffs in 2008.

Joe Flacco. When sports people talk about “a cannon for an arm” Joe Flacco is the kind of guy they are talking about. The big right arm won the New Jersey native a full scholarship to the University of Pittsburgh in 2003 but it was not enough to earn him much playing time. He completed one pass for eleven yards with the Panthers and decided to transfer to lower division Delaware.

Flacco was the Blue Hen starter in 2006 and 2007, leading Delaware to a modest 13-9 record. But in a foreshadowing of what would come in his pro career Flacco seemed to save his best games for the biggest moments. He engineered a 59-52 upset of the Naval Academy by tossing for 434 yards and four touchdowns with no interceptions. In the 2007 playoffs Delaware, seeded #13, surprised top-seeded Northern Iowa and #4 seeded Southern Illinois on the road to advance to the national championship final. Flacco threw for two touchdowns in each game. Delaware fell to Appalachian State 49-21 in the title game.

Flacco’s brief stay in a Blue Hen uniform produced 20 school records and the following spring the Baltimore Ravens made him the first University of Delaware player drafted in the first round. Flacco wound up starting every game as a rookie in 2008 and won two games in the playoffs as he went from Newark to NFL Rookie ofthe Year. In the 2012 season Flacco led the Ravens to the Super Bowl championship as he tied a postseason record with eleven touchdown passes and no interceptions. His postseason playoff record through 2015 in the NFL was 10-5, including a record seven wins on the road. And that does not include his two in Newark.

CHUCK HALL

George Lacsny was the University of Delaware’s Wally Pipp. Like the excellent Yankee’s first baseman who got hurt and forever surrendered his job to Lou Gehrig, Lacsny was the Blue Hens’ starting fullback until he was sent to the bench by a second quarter injury against Hofstra on September 21, 1968. Sophomore Chuck Hall trotted in and galloped for 127 yards in the 35-0 romp. Before he graduated three years later Chuck Hall would rush for 3,157 yards, one of a host of school records he set. The Springfield, Pennsylvania native was named a Little-American in his senior year.

Hall joined the Baltimore Colts in 1971 but a shoulder operation put him out for the season. The next year Hall was invited back to training camp but he was already in the early stages of the Hodgkins Disease that would claim his life at the age of 24. Chuck Hall became the standard against which all future Delaware runners would be measured.

TEN HISTORIC RIVALRIES

Bucknell. A heated rivalry brewed between Delaware and Bucknell for most of the time the two fought in the Middle Atlantic Conference. Begun with a game in 1908 the series picked up in earnest after World War II. In 1949 the Bisons denied Delaware an undefeated season, dealing the Blue Hens a 13-7 loss in Lewisburg. Beginning in 1950 the Delaware-Bucknell clash was the traditional season-ending game for the Blue Hens. Curiously the Bisons would add the dreary exclamation mark to each of Delaware’s five losing seasons during their post World War II rivalry with losses in that final game, four at Delaware Stadium.

In 1951 powerful Bucknell rolled over Delaware 33-6 in front of a home crowd whipped into a frenzy by frequent public address announcements of records repeatedly broken by one of the finest Bison teams ever. Delaware extracted revenge the next season by dumping the Bisons 13-0 in the mud at Delaware Stadium to derail a championship Bucknell season. The Blue Hens would reel off seven straight wins in the series.

The highlight came in 1962 when both teams reached their climactic final game undefeated in the Middle Atlantic Conference. The struggle for the conference title would be one familiar to Delaware fans over the years: a high-powered aerial attack against Delaware’s fabled Wing-T-fueled ground game. Both Delaware and Bucknell were able to find easy going in the middle of the field but both defenses stiffened in defense of their own goals. Despite the wizardry of Bucknell quarterback Ron Giordano who, the Evening Journal reported, “turned in the finest individual performance against a Delaware club,” Delaware was able to come away with a 9-6 classic win.

The series ended in 1985 when Delaware entered the Yankee Conference with the Blue Hens handily on top 22-11. Looking back Delaware could always gauge the success of its season by the Bucknell game. Only three times did Delaware ever lose to the Bisons during a winning campaign and never defeated them during a losing season.

Delaware 23, Bucknell 11

Colgate. As rivalries go this one sported neither tradition nor longevity. But each time the Red Raiders flashed on the University of Delaware schedule it was the biggest game of the season for one school or the other.

In 1977 Division I Colgate was undefeated, untied and ranked #19 in the country when they stopped in Newark to primp for a postseason bowl appearance. The Blue Hens were no strangers to strong Division I teams but this Delaware squad was seemingly the weakest in a decade. The first six games resulted in three losses, a tie and a narrow two-point home decision over West Chester. Accordingly area Colgate alumni staged a “Victory Party” the Friday evening before the game.

Anxious to spotlight the high-powered Red Raiders, ranked number one in the country in total offense, ABC-TV offered to make the Delaware-Colgate game the second half of its nationally televised doubleheader - if Delaware agreed to move the game to Philadelphia. Feeling his obligation was to the students and Delaware football fans Athletic Director Dave Nelson turned down the guarantee of $175,000 to take the game off campus. The capacity crowd of 23,029 would not be disappointed.