Horse Racing In Delaware

Dover: Fairview Park

The Delaware State Fair opened for business in 1878 and right from the start its trotting races were the best on the Delmarva Peninsula. Fairview Park, built to be one of the finest tracks in the country, was beautifully situated at the end of the railroad lines. More than 3000 people were on hand by the final day of the inaugural week-long event. The feature race that day carried a purse of $1000, the largest yet seen in Delaware. Driver stepped to victory in three of the four heats to win the grand prize in the 2:22 class.

The next year between 10,000 and 20,000 people poured into the fairgrounds and the renewal of the 2:22 class provided the finest contest ever witnessed on any race track in Delaware. The favorite Irene finished last in all five heats of the four-horse affair. May nipped Jersey in each of the first two heats but the lightly regarded Scotland thundered from behind to win the final three heats and the race.

By 1880 the Dover races, in only their third year, were far and away the class of the state. While the Wilmington Trotting Association had to cancel their meet because it couldn’t fill the fast classes Driver sped across the Fairview Park oval in 2:23, the fastest race time ever in Delaware. In a special race to beat 2:19 1/2 for $1000 the little mare Trinkett, in the hands of trainer John E. Turner, took the track on a frigid October day before 5000 people. With 50 stop watches trained on her she reached the half in 1:09 and raced to the wire in 2:19 1/ 4 to claim the thousand dollars.

Record-setting driver John E. Turner guided many champions on Delaware tracks. Here he is depicted by Currier & Ives driving the grand trotter Edwin Thorne.

The performance thrust Trinket into the first ranks of racehorses, causing Farmer’s Magazine to gush the following year, “The young mare Trinket has been most carefully wintered, and is now in the most splendid form and condition. If this mare does not develop into one of the great lights of the trotting turf, then all the flattering and promising indications of the past will go for naught.”

Dover’s reputation for fast horses was firmly established and the State Fair became an anchor of the Peninsular circuit with race tracks in Elkton, Baltimore, Wilmington and Easton. The races at Fairview Park continued throughout the 19th century, making the Delaware State Fair the longest success story in Delaware racing in the 1800s.

DOVER: DOVER DOWNS

Horse racing at Dover Downs, restricted to the bleak winter months has proven somewhat less popular than the NASCAR oval encompassing it. The first thoroughbred meet in 1969 averaged only 2,775 fans, barely half of what was expected. Attendance topped out at 3500 in 1972 but flat racing was gone from Dover Downs by 1975. Harness racing fared somewhat better. Operating in the dead of winter Dover developed a reputation as a track that put on racing without the questionable shenanigans that oft times tainted larger plants. Horsemen enjoyed the friendly atmosphere and excellent racing surface. Attendance was on par with the thoroughbreds and reduced expenses in the harness game allowed it to survive.

The small purses at Dover seldom enticed the sport’s leading performers to the track on Route 13. But occasionally one would show up. Meadow Rich established a mark for older horses at Dover with a 1:58 mile in 1985 and the next year Forrest Skipper dropped by to shatter the track record in 1:54.4 on his way to Harness Horse of the Year honors.

By the 1990s Dover Downs and Harrington were operating on limited weekend schedules. They were the last harness tracks still operating in Delaware, where once, only a score of years before, there had been four. The oldest sport in Delaware was in danger of being put down.

On December 29, 1995 the Horseracing Redevelopment Act gave people legal slot machines and Dover Downs fatter purses. Much fatter purses. Before the slot machines Dover Downs would offer a desultory card of races with purses of $800, maybe $1,000. With the infusion of slot profits a ten-race program would average $150,000 in prize money for the night.

The difference on the track was immediate. Dover was flooded with the game’s best horses and on November 16, 1996 the pacer Riyadh ran away from the field in a $20,000 Open mile pace to set a track record of 1:49.1. There would be no tickets cashed on Riyadh this night - the six-year old who was brought back from retiring after failing in the breeding shed was barred from the wagering.

Dover Downs became a destination stop on Monday nights when heavy hitters like Jet Log with Canadian Luc Ouelette would battle Pilgrim’s Fiery with Eddie Davis. The slot money also improved homebred Delaware racing stock. Rainbow Blue, training out of Harrington by George Teague, Jr., became the first Delaware standardbred since Adios Harry a half-century before, to garner national acclaim.

In 2004 the filly won 20 of 21 races and was named Horse of the Year, one of only three fillies ever so honored. In only two of her wins was another horse even within one length of her at the finish line. Rainbow Blue posted a stakes record 1:51 mile at the Breeders Crown.

Rainbow Blue began her four-year old campaign with four wins in four outings before a tendon injury ended her career. She won 30 of her 32 lifetime races and owned two of the three fastest miles ever paced by a three-year-old filly (1:49.2 best) when she retired. Rainbow Blue would be inducted into the Harness Racing “Living Horse” Hall of Fame in 2012.

GEORGETOWN: GEORGETOWN RACEWAY

For years the Del-Mar-Va Racing Association held the franchise to harness racing in Sussex County granted by the Delaware Harness Racing Association. Each season Del-Mar-Va would thus get a share of profits from Harrington and Brandywine without ever staging a meet.

Sussex County had traditionally been an excellent breeding and training area for standardbreds so when plans were finally announced to build a harness track on Route 18 outside Georgetown there was a paddock full of investors ready to back the venture. People from the big cities come to lower Delaware every summer for the beaches so why wouldn’t they come back in the winter for harness racing?

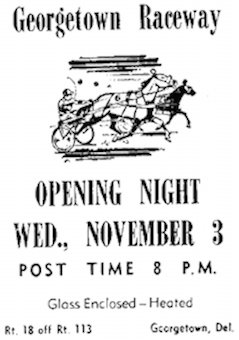

The stands were still not enclosed and there weren’t any heaters and there were no lights in the parking lot and much of the $1.5 million facility was still unfinished but on November 3, 1965 winter horse racing came to Delaware. But even though the half-mile track and the parimutuel windows were about the only things ready when Pearl C, a Delaware horse, flashed across the wire in 2:11.1 to pay $8.80 in the inaugural pace, Georgetown Raceway was off to a successful first meet.

To lure horsemen in the dead of winter Ed Keller, director of racing and future Harness Racing Hall of Famer, instituted a policy of distributing the purse among all the starters - making Georgetown the first track in the United States to do so. Racing on nights and Saturday afternoons from November to February the Georgetown Raceway averaged about 2,200 in attendance and $90,000 in handle - 10% above projected levels of profitability.

Operating with the bottom-of-the-barrel dates not assigned to Brandywine and Harrington the little track continued to prosper. The drivers liked it and fans - drawn from far-away Baltimore, Washington and Philadelphia - loved their side trips down the Delmarva Peninsula. But with Dover Downs opening in 1969 Delaware could not support four harness tracks and Georgetown was fourth in this four-horse race. A spring meeting of 21 nights was tried in direct competition with Brandywine, Atlantic City Race Course and Rosecroft and Laurel in Maryland. Despite this suicide run Georgetown still averaged 1754 fans but new owner John Rollins, who also operated Brandywine and Dover Downs, gave Georgetown’s remaining 1970 dates to Dover.

The abandoned facility quickly deteriorated and Rollins sold the dilapidated property to a Maryland convenience-store owner for $167,000, with the provision he not race horses there for ten years. Plans were hatched to race stock cars and even dogs but both ideas were dropped after strong opposition in the community. Eventually after nine years as a deepening eyesore the former jewel of Sussex County racing was converted into a training center and farmers market.

HARRINGTON: HARRINGTON RACEWAY

Just as harness racing in Delaware was about to go the way of the hitching post in 1920 the Kent and Sussex County Fair Association formed for the purposes of “giving pleasures and diversions to the inhabitants of rural communities within the state of Delaware.” One of the centerpieces for the new Fair was harness racing. Thirty acres for a track and grandstand were acquired for $6000. For the next decade these four-day meets provided the best horse racing in Delaware.

In 1946 the old Fairgrounds were spruced up a bit and Harrington hosted Delaware’s first pari-mutuel night harness racing. Cards were typically eight races, run for purses of $300 and $400. The track was only wide enough to accommodate six horses so two horses broke from the second tier. Crowds estimated at 3000 turned out for Opening Night, a Monday, and didn’t abate for the entire 15-night meet. Organizers hadn’t imagined that kind of revenue. And the weather had been lousy.

The star driver of that first meet was Elbert J. Saunders, 72, in his 57th year at the reins. Saunders estimated he had driven horses 300,000 miles, but never on Sunday. The Sabbath was for church or “courting.’” He held several track records around the fair circuit and at the age of 70 drove in six heats in one day and won five. At Harrington Saunders guided Performance to the meet’s best 9/16 mile time of 1:08 3/4.

Harrington Raceway is the oldest continually operating racetrack in the state of Delaware with races on the same oval for more than 95 years. It is the last existing track to have featured both horse racing and auto racing over the same surface. On August 2, 1947 Harrington set a record for attendance at an auto race that was not approached until the construction of the modern speedway at Dover Downs. That day 36,258 fans jammed the old track to watch the big autos through plumes of dust.

In the Spring 1947 meet the handle went over $1 million at Harrington. In 1948 a $1000 stakes race was added to the program and a mobile starting gate introduced. That year each winning horse was awarded a blanket. By 1951 the average attendance was 2500 and the daily play over $60,000. That year Royal Mist set a world’s record for two-year old fillies, pacing the 1/2 mile oval in 2:05.

But the Kent & Sussex Raceway in Harrington, which had been the sole nourisher of harness racing in Delaware for 34 years, was about to be pushed aside. With the coming of high-profile Brandywine Raceway in 1953 the Delaware Harness Racing Commission was obligated to award the prime racing dates where it could generate the most revenue. And that meant bustling New Castle County, not rural Kent County.

Each year Harrington was dealt increasingly worse racing dates. But the track survived and even broke attendance and handle records in the 1960s. The racing was in the century-old tradition of owners trucking their animals off the farm to test each other. With its low overhead Harrington was the only Delaware racing plant able to make a profit. But even Harrington’s minimal expenses could be offset by the decline in interest in standardbred racing.

Racing was sporadic in the 1990s until the installment of the first of more than 2,000 slot machines in 1996. About 10% of all the revenue funnels straight into race purses and Harrington began offering horsemen some $135,000 a night. In 2003 the half-mile oval was given wider turns and faster times. In 2015 Wiggle It Jiggleit blazed to a track record in 1:49, one of 22 wins for the three-year old gelding in 26 tries. After pocketing $2.18 million in winnings and the Little Brown Jug, harness racing’s crown jewel, Wiggle It Jiggleit became Harrington-based owner George Teague, Jr.’s second Horse of the Year.

MIDDLETOWN: GENTLEMAN’S DRIVING PARK

On May 26, 1874 the following letter appeared in Every Evening, “The Middletown Agricultural and Promological Association have laid out and graded their trotting course and will soon have it ready for use, and I challenge you Wilmington sports to come down with their fast nags.”

Over the next decade the Middletown Fair races prospered in the Delaware horse racing community. By the the third annual meeting the Middletown races were attracting 80 entries for the three days of racing. That year more than 4000 people paid the 50-cent admission to see Sadie Bell, the popular Virginia import valued at $50,000. The first day Sadie Bell swept two heats to win a minor purse and on the final day easily won all three heats in the feature, blazing the first-half mile in the last heat in 1:06. Middletown was at the pinnacle of Delaware racing.

For the rest of its existence the Middletown races were eclipsed only by the state fair in Dover. Crowds were consistently in excess of 3000 for the annual fall meeting but the organizers found it increasingly difficult to meet expenses and closed down the Middletown fair races in 1883. Thereafter, racing was contested at the Gentleman’s Driving Park on a limited scale, seldom bringing more than 250 people to the old track.

NEWARK: HOMEWOOD PARK

Newark established what may have been the first formal race course in Delaware in 1760. In 1877, a pristine race track was constructed on the Holtzpecker farm in Newark, just outside the tiny village. It was announced by relieved observers that, “now we will know who has the fastest horse without endangering the lives of our people.”

Newark sportsman and cricketeer William Homewood purchased the property and in 1882 the Homewood Trotting Park Association was organized. The half-mile track operated on a small scale for local horses. Purses were arranged for $15, $30 and $50. Crowds seldom exceeded 800 for the occasional races and the genial affairs were said to be “unattended by the objectionable features generally ascribed to such gatherings.”

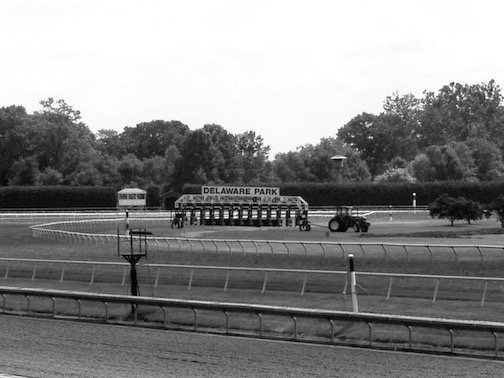

STANTON: DELAWARE PARK

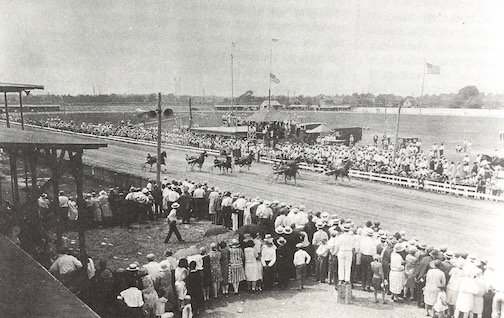

On July 5, 1954 there were 35,473 people basking in the sun at beautiful Delaware Park enjoying an eight-race program. It was the largest crowd ever to see horse racing in Delaware. The crowd bet $2,227,562, the most money ever wagered in one day at a state race track. And there was only daily double, win, place and show betting available - no exotic wagering options like exactas and trifectas.

Delaware Park was the most magnificent sporting palace ever built in Delaware. In the 1950s Delaware Park was on a short list with Saratoga as a place to find racing in the grand tradition. And it was one of the busiest; only eleven tracks in the country handled more than the million dollars or so bet every afternoon in Stanton.

Fifty “horse-minded people in the community,” as the instigators have been described, led by William du Pont Jr., helped push through Delaware’s first racing legislation on February 6, 1935. These sportsmen were not interested in making money but were just looking for a place to run their horses. That the public could come and bet a few dollars was a necessary evil. And Delaware Park has always been run as a nonprofit track.

Delaware Park opened on June 26, 1937 on 450 acres of farmland southwest of Stanton and it was spectacular. There were seats for 7,500 fans and stables for 1,226 horses. Both were filled to overflow. The plant was said to cost $1.25 million and was billed as “the lastword in safety and comfort.” Over $50,000 was spent on the shrubbery alone.

Delaware Park was the First State’s first major league sporting venue.

The new track was in an ideal competitive position. There was no racing in Maryland or New Jersey; pari-mutuel wagering was illegal altogether in Pennsylvania and there was no night harness racing. The railroad tracks that ran right to the front gate brought fans from Washington to New York. A roundtrip ride on the Pennsylvania Railroad from Wilmington could be had for 30 cents.

There were five $10,000 stakes races on Opening Day and 18,000 people turned out to see Legal Light win the first race, galloping five furlongs in a minute. By the time the 24-day meet ended the crowds were so large du Pont started plans to double the size of the grandstand. The handle was $6,368,031 and $217,680 went into the Delaware treasury - without a penny of investment from the state.

Delaware Park was the state’s entry into big league sports. The roll call of jockeys and trainers who campaigned at William du Pont’s track reads like a Hall of Fame induction ceremony - Eddie Arcaro, Bill Shoemaker, Angel Cordero, Ron Turcotte, Henry Clark and so on. Delaware Park was recognized around the country for the grace and beauty of its racing. In 1953 the Kent Handicap became the first nationwide telecast to emanate from Delaware.

Once inside the three tree-lined entrances at Delaware Park it was truly the “Sport of Kings.” The salad days at Delaware Park lasted about a quarter of a century. By 1960 the competition for the entertainment dollar - both inside and outside of racing - became stultifying. Brandywine Raceway, although a nighttime operation, encroached on Delaware Park’s racing dates for the first time in 1960. Then Liberty Bell Park in Pennsylvania began siphoning off the lucrative Philadelphia trade.

The decline in attendance and handle continued steadily until 1982 when directors of the track announced there would be no racing in 1983. To that point Delaware Park had generated $80 million in tax revenue over its 45 years of operation. Racing was revived in time for a golden anniversary in 1987 and the track limped forward, buoyed by simulcasting and the fiduciary promise of slot machines.

When the one-armed bandits finally arrived even track officials were stunned by the impact - over $6 million a day was pumped into Delaware Park video terminals. The signature Delaware Handicap eventually became a $750,000 race. Quality thoroughbreds like Triple Crown race winners Barbaro and Afleet Alex won their maiden races in Stanton. Delaware racing was back in the big leagues.

WILMINGTON: SCHEUTZEN PARK

The earliest racing in Wilmington was through the city streets, often for stakes put up by the competitors. Delaware statute proscribed gambling on horse races in 1829 but street racing had become such a nuisance by 1833 that a city ordinance was issued that stipulated: “If any person shall drive or ride a horse, horses, beast or beasts of burden in running or racing with another horse, horses, beast, or beasts of burden, in any street, lane or alley of this City, every person so offending shall be guilty of a common nuisance and for every such offense shall forfeit and pay a fine of twenty dollars.”

Outside the city the roadway past Hare’s Corner, where Budd Doble, proprietor of the Hare’s Corner Hotel would eventually build a popular track, became known as New Castle County’s most notorious racing ground. Efforts to establish racing on a track in Wilmington met limited success until September 25, 1871 when Scheutzen Park opened out on the Kennett Pike.

The meets typically featured three races a day, to be contested in heats. The first horse to prevail in three heats would be declared the winner. Purses ranged from $50 to $300 with 10% of the purse required as the entry fee. Fields were set based on lifetime marks of the horses with the slowest races featuring 4:00 horses and the fastest competing in 2:30 and better classes. In addition to trotting and pacing races there were occasionally double-team and thoroughbred tests added to the program. Some horses were driven by professionals but most, especially in the slower classes, were under the reins of the owner.

The races were characterized by many false starts and required the better part of the day to complete, if the heats could be squeezed in before nightfall at all. Although gambling was illegal, nor was it always discouraged. It was not uncommon for drivers to be set upon by disgruntled bettors after a race and often the fastest running a horse was urged to do was in flight from the grounds.

This unsavory element to the sport helped undermine the popularity of racing in Wilmington through the years. During several periods racing died out in the city totally; other years the Wilmington Trotting Association was able to present the strongest racing in Delaware. In the spring meet of 1877 the two most popular horses on the Peninsula, Delaware and Sadie Bell, tangled in a best-of-five race with each trotter winning two and a fifth race finishing in a dead heat. Later Delaware beat Sadie Bell by 150 yards when she broke as the betting favorite.

As a result of the break a $50 winner-take-all match was set up between the two horses and twice Delaware ran down Sadie Bell in the stretch to win. In the fall the two engaged again at Scheutzen Park with the same result: Delaware and Sadie Bell won two heats apiece with a dead heat. Neither of the two exhausted horses however could capture the decisive third heat and Jersey Boy won the race by winning the sixth, seventh and eight heats before an enthralled crowd of at least 2000.

Sadie Bell, a four-year old record-holder from Virginia, was one of the most popular horses at Scheutzen Park and other Delaware tracks.

In 1890, after another slack period of racing, Scheutzen Park was revived as the Wawaset Driving Park. Races were now contested on a strictly amateur basis. No purses were offered and horsemen competed only for coveted blue ribbons. Under these conditions racing at the old track flourished.

In 1902 the Delaware Horse Show Association organized to present fancy horse shows on the Wawaset grounds. As a secondary attraction a few races were staged to show the horses to best effect. So popular was the sideshow that by 1904 the horse shows were abandoned completely and the Wawaset Driving Association was formed to hold matinee races. The matinee races, run twice a week, were a staple of the Delaware sporting scene. The membership in the Driving Association grew to more than five hundred business and professional men from the Wilmington area and became a central element in the social life of Wilmington.

For more than a decade local harness racing fans enjoyed the matinees. Thousands attended and Delaware became recognized as a matinee racing center of the United States. Several nationally known horsemen graduated from the matinees to the stakes races of the Grand Circuit. But these affairs remained for amateurs only and fans would delight in the occasional entry of a horse like Prince, a bay gelding who could be seen away from the track on the streets of Wilmington pulling a milk wagon. Prince could trot the mile in 2:30 and sometimes defeated his “unemployed” competitors.

Racing for purses returned to Wawaset on July 4, 1912 as part of the program for the New Castle County Fair. Purses varied from $400 to $1000 and attracted leading horses from all the eastern hotbeds of harness racing. Intercity racing, with the pride of Wilmington horsemen on the line, wasespecially popular.

Wawaset, nee Scheutzen, Park was in the homestretch, however. After World War I the grand old track, nearly 50 years old, was sacrificed for the residential migration away from the city.

WILMINGTON: HAZEL DELL PARK

As part of the backlash against gambling and other unsavory goings-on around Wilmington horse tracks George Lobdell of the Lobdell Car Wheel Company built the Hazel Dell Driving Park in 1885 near his car works on the south side of Wilmington. Here gentleman drivers could come and test their fast horses. Horsemen paid a $10 subscription and were given the privilege of a first class track without the costs and drawbacks of a professional trotting course.

No premiums were offered and no betting allowed during the races. Still, 2000 turned out for the first meet at Hazel Dell and regular events consistently brought 1000 or more race fans to the track. In 1888 the first Wilmington Fair was held on the Hazel Dell grounds. The fair was a huge hit with daily crowds exceeding over 20,000 - the largest crowds ever to gather on the Peninsula.

The second Wilmington Fair in 1889 was an even more phenomenal success. Up to 40,000 people crowded into Hazel Dell on “Big Thursday,” the traditional day for the week-long fairs to peak. More than 15,000 watched the trotting races that day, which now included the Brandywine Stakes for $500 and the Diamond State Stakes for $1000.

The fair continued for only three more years before it collapsed under the weight of its own popularity. More than a dozen speakeasies sprouted around the edges of the fair and the organizers were forced to place many restrictions on the exhibitors and attendees. Enough rebelled to spell doom for the great carnival.

WILMINGTON: BRANDYWINE RACEWAY

In the fall of 1953 Brandywine Raceway became the 28th night harness track in America and the first in the Delaware Valley. Special buses were chartered to accommodate race fans in neighboring towns but track officials still weren’t prepared for the onslaught of people eager to welcome Brandywine. Traffic was so congested on the feeder roads leading to the track at Concord Pike and Naamans Road that people within a mile of the track at post time didn’t place a bet for two more hours. The official tally was a near-capacity 14,184 and the handle was $314,062.

The first 20-night meet featured six rich stakes in the first week which lured some of the country’s leading standardbreds, including Direct Rhythm, the world’s fastest living pacer. There were 13 live telecasts on WDEL-TV from Brandywine that year. When the Big B, as the track came to be affectionately known, finished racing in 1953 only Yonkers Raceway had ever enjoyed a more prosperous first year.

In 1954 Brandywine’s $400,000 in purses brought the sport’s best drivers to Delaware. But among Billy Haughton, Stanley Dancer and Del Miller the driving title went to Harrington’s Henry Clukey with 16 wins. Later Herve Filion would win a large chunk of his most-ever career wins at Brandywine.

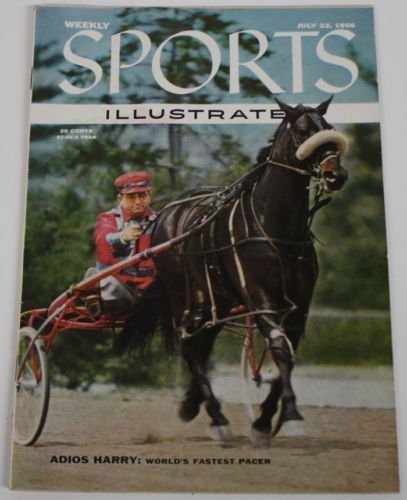

Over the years all the great standardbreds appeared on the Brandywine oval. Two of the first were Adios Harry and Adios Boy. Adios Harry was owned by Harrington chicken farmer J. Howard Lyons who had bought the colt for $4200. In 1954 the Delaware runner won the Little Brown Jug, one of pacing’s Triple Crown events, and in 1955 the 4-year old brown stallion set a competitive harness race record of 1:55 at Utica’s Vernon Downs. For his part Adios Boy had four world records to his credit.

The half-brothers met six times before coming to Brandywine for the $15,000 Good Time Pace. Harry won all three match races and Boy won all three stakes races. Stunningly, neither would triumph on Brandywine’s half-mile oval. Adios Harry broke and both he and Adios Boy finished out of the money behind 24-1 longshot Hillsota.

The next year Adios Harry returned to Brandywine and set the track record at 2:00.3, beating Meadow Rice’s 2:01.1 which had been established in the first meet. Speedy Pick later lowered the track record to 2:00.1 but no horse recorded a sub-2:00 “Magic Mile” until one night in 1960 when four horses flashed under the wire in less than 2:00 in the same race. Adios Butler won the race in 1:58.4 followed by Tar Boy, Speedy Pick and O.F. Brady. No horse ever went faster on Brandywine’s half-mile track.

By the end of its first decade Brandywine Raceway had established itself as one of the most beautiful and profitable racing plants anywhere - the grandstand was built facing west so patrons could enjoy the sun setting over the track. In 1966, a record 22,177 jammed the track to see Bret Hanover win his 47th race in 50 starts in a duel with Cardigan Bay. A rarity also occurred that year, on April 26, when the eight horses crossed the finish line in the exact order of their post position.

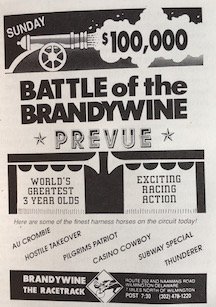

The annual renewal of the Battle of the Brandywine was the Delaware Valley’s richest harness race, attracting the best standardbreds in America.

In 1970 Brandywine’s original half-mile track, one of the fastest in the nation, was converted to a five-eighth mile oval. On July 3, with free admission to the grandstand, Brandywine established its all-time attendance record of 25,278. The track was still profitable but the peak years had passed. The handle had been declining since 1962 when the average play was $665,425 a night.

By the 1980s Brandywine was draining more than a million dollars a year from its owners. The great horses still turned out - Niatross, Direct Scooter and Rambling Willie - but the Atlantic City casinos were stealing the high rollers. Nightly play was less than half of its glory days of the 1960s. By the end of the decade, despite the closing of its main competition in Liberty Bell Park, losses mounted to over two million dollars a year. There would not be a 1990s for the one-time showcase of harness racing. It closed in 1990, left to stand as a weedy monolith in the residential Brandywine Hundred landscape until its destruction for a big box mall.

THE FASTEST RACE TRACK IN AMERICA

In 1890 the first so-called kite track opened in America in Independence, Iowa. The track featured a long straightaway into one long turn and another straightaway back to the finish line. With one turn instead of two the new track was graded six seconds faster than a regulation track. When Governor Leland Stanford of California opened a kite track in Stockton six world records fell in a single week.

Late in 1891 Dr. J.C. McCoy of Middletown began work on the first kite track in the eastern United States near Kirkwood, Delaware. McCoy employed 80 men for ten weeks to build his racing palace which featured stables for 190 horses and a grandstand to hold 3000 spectators. The track cost $50,000 to build, including $10,000 for an ingenious sprinkling system that could water the entire track in 1/2 minute from over one mile of 2” pipes.

The Maple Valley Trotting Association debuted the innovative track in 1892 for reporters and horsemen from Philadelphia, New York and Baltimore. The pundits quickly anointed McCoy’s kite track as the swiftest surface to be found anywhere and preparations were made for a grand opening on July 4. Despite a multitude of other Independence Day events more money than 8000 race fans descended on Kirkwood. By 10:45 in the morning ticket sellers were overwhelmed.

Doc, an Irish Setter from Canada, was the big crowd-pleaser at Kirkwood.

The crowd was treated to its first world record when the trotting team of Belle Hamlin and Globe went the mile in 2:12 to break their own record by a full second. Next onto the track was Doc, The Trotting Dog. Doc was enormously popular, earning his master Willie Ketchum more than any horse. Willie, perched in a diminutive sulky with pneumatic tires, guided the “Canine Wonder of the World” to a personal best of 48 seconds for the 1/4 mile. Adoring fans mobbed Doc, who then returned to the track and ran down a Wilmington man in a man-versus-dog sprint in front of the grandstand.

In the feature Hal Pointer trotted onto the kite track to thunderous applause in a special race against time for the world record. Hal Pointer was only able to go the mile in 2:11.3, well short of Direct’s mark of 2:06, but he was only rounding into form. A month later he would shatterthe world record.

Racing at Kirkwood continued through the year, bringing a succession of personal bests for both horses and bicyclists. In 1893 McCoy prepared an even greater day of racing for July 4. He lured Mascot, the world record pacer with a 2:04 mark, to Kirkwood with an offer of $5000 for a new record. Challenging Mascot was Saladin, the Delaware champion with a world record 2:09 on a half-mile track to his credit. In the hyperbolic journalistic style of the day it was said that, “if the race had taken place in New York or Philadelphia it would attract a million spectators.”

But it was the last hurrah for McCoy’s celebrated kite track. With the introduction of the bicycle sulky the speed advantage of the track was no longer so apparent and the public objected to the configuration because it took the horses so far from the grandstand. Kite tracks disappeared everywhere, leaving a brief, but thrilling legacy.

SLEIGH RACING IN DELAWARE GREEN

In the 1800s before a winter snowfall had even ended, people began to anticipate the upcoming sleigh races through Delaware city streets. In Wilmington the raceway ran along French Street from 11th to the finish line at 2nd Street. Both sides of the street would be lined with racing fans who congregated from all parts of the area to witness the thrilling spectacle of horses and drivers flying all-out down the slippery hill to the railroad line at the foot of French Street.

The “brushes” were unofficial sport with no set of rules or formal starter. As the sleighs gathered near the starting line one horse would break and the others would un-rein in frantic pursuit. Plumes of snow exploded far into the air from the charging steeds as they raced between wildly partisan supporters. Even in the snow most horses performed at speeds estimated at 2:40 or better for a mile but many horsemen withheld their best horses due to the dangerous element of the event. Fans described the sleigh racing on French Street as the most exciting sport they had ever witnessed.

Other Delaware communities, although less geographically blessed for breakneck downhill races than Wilmington, engaged in sleigh racing. Town authorities in Milford cordoned off Northwest Front Street as a race course and diverted traffic to give the racers a clear path. In Lewes the sleigh races were held on a main street; in Townsend the course went down East Main Street. In Newark the races started at the B & O track next to the Deer Park Hotel and finished in front of the old Washington House at the railroad crossing by the present Newark Shopping Center. These brushes would attract as many as 50 to 100 horses, the best in the area, all in quest of the silver cups awarded to winners.

Winters were colder and snows heavier in Delaware a century ago which contributed to the sport’s popularity. Enthusiasts often hauled snow to patch dry spots and maintained the course by sprinkling it with water. Sleigh racing remained popular in Delaware up to the 1920s when it became more of a priority to clear snow from city streets rather than groom it.

DELAWARE DERBY HORSES

Although various scions of the du Pont dynasty have been among the most prominent horse owners and breeders in the country other Delawareans, including businessmen and farmers, have sent just as many hopefuls to the post in the Kentucky Derby.

After undistinguished performances by Gold Seeker, 9th in 1936; and Fairy Hill, 11th in 1937; Delaware’s first great chance for a Derby winner was Dauber in 1938, a grandson of the immortal Man O’War, owned by William du Pont and developed at the Bellevue squire’s Foxcatcher Farms. Du Pont purchased Dauber late in his 2-year old season in 1937 for $29,000. He never liked the colt as a runner; he started slowly and finished fast as he got his legs underneath him. But Dauber was a great mudder and competitor and got to the Derby as a mid-range longshot.

True to form Dauber got off to a terrible start at Churchill Downs but by the time he reached the grandstand Delaware jockey Maurice “Moose” Peters had locked 9-1 shot Lawrin in a stretch duel. Lawrin nosed Dauber under the wire as the Delaware horse paid $12 to place and $6 to show. In the Preakness Dauber caught a muddy track at Pimlico Race Course and romped home 7 lengths the best as a 3-2 favorite. Despite the off-track Dauber raced to the finish line in 1:59.4, only three ticks off the old track’s record. In the Belmont Dauber went to the post as the heavy favorite but was nosed out by an 8-1 shot Pasteurized.

Dauber suffered a bowed tendon in his ankle and was retired. Du Pont did not see him as a great sire and sold Dauber for $45,000. Six months later du Pont’s acumen for horseflesh was proven out when Dauber was resold for only $29,000. The horse that finished less than a length from the Triple Crown in 1938 produced a very mediocre crop at stud.

The 1940s saw a string of Delaware horses ship to Louisville. Fairy Manhurst finished 13th in 1942 and Alexis completed a middle-of-the pack run to 10th in 1945. In 1946 William du Pont’s Hampden raced home an impressive third from the far outside post behind Triple Crown winner Assault. Also that year Double J, owned by Wilmington restaurateur James Boines and liquor dealer James Tigani, was the best 2- year old in the country. In ten starts he won six and was never out of the money. But Double J came to the 1947 Kentucky Derby overworked and wound up a fading 12th.

The Wilmington horse recovered to take four stakes races including the Garden State Stakes, Benjamin Franklin Handicap, Jersey Handicap and Trenton Handicap. He set the Garden State Park track record and retired as the all-time leading Delaware money winner with $299,810.

After Wilmington’s Greek Song fizzled in Kentucky in 1950 the state of Delaware was thrust into the national spotlight with a Derby favorite in 1951. Repetoire was an overlooked colt when he was bought for only $4000 at the Saratoga Yearling Sale by Stanley Mikell, Dover businessman and councilman. Repetoire won four straight minor stakes races - the Remsen, Cherry Blossom, Experimental and Chesapeake. But when he won the Wood Memorial Derby prep at 7-1 Repetoire was suddenly the “hot horse” for Derby handicappers.

Repetoire was not a prohibitive favorite in a wide-open race. His gameness was unquestioned as all five of his wins had come by less than 3/4 of a length. But his inability to distance himself from other 3-year olds in these battles cast doubt as to his true greatness.

In what was becoming a regrettable Delaware tradition Repetoire drew the far outside post - Post 21. Unable to overcome his starting gate handicap Repetoire came in 12th behind Count Turf, who emerged from the field to win the 1951 Kentucky Derby. He retired the following year as a 4-year old with lifetime earnings of $112,095.

In 1956 Countermand began his career only a month before the Derby and reeled off first and third place finishes at Keeneland Race Track, a 4th in the Blue Grass and a second in the Derby Trial. This crash course in preparation sent Countermand, from Brandywine Stables, off at 6-1 – despite commandeering the “Delaware Post,” #17 in a field of 17. The green Countermand was overwhelmed from the start and galloped home last.

Bayard Sharp’s Trolius led the 1959 Kentucky Derby to the half but finished last of 17 horses and never raced again. The inexperienced Holy Land came to Churchill Downs after three early-season wins at Gulfstream Park. In the Kentucky Derby Holy Land ran in traffic and clipped another horse’s heels, spilling jockey Hector Piler and sidelining him for six months.

Arlene Daney of Wilmington shipped Parfaitement to Louisville in 1983. The colt had won five of six starts as a two-year old but was left far behind as a 20-1 longshot in the Derby, whipping only four foes in the 20-horse field. Two weeks later in the Preakness backers of Parfaitement could cash a winning ticket, however. Although the Delaware horse finished 8th he was coupled as an entry with winner Deputed Testamony.

John F. Porter founded the Wilmington Auto Sales in 1925 to sell Chevrolets and Buicks. The same year he started Porter Chevrolet in Newark and through the years there would be as many as 15 Porter dealerships. The third generation owner of the Porter Chevrolet Group, Rick Porter, harbored a fascination for a different type of horsepower. He had grown up attending races at Delaware Park and in 1994, at the age of 54, Porter began buying inexpensive claiming horses.

His first stakes winner was Kentucky-bred Jostle in 1999. When Rockport Harbor won all four of his races as a two-year old in 2004 he was an early-line Kentucky Derby favorite but a right hind foot injury caused him to miss the 2005 race.

Hard Spun also enjoyed an undefeated two-year old season in 2006, sweeping to three victories. The big colt out of one of America’s leading sires, Danzig, won two more races early in 2007 and became Porter’s first Derby horse. Hard Spun went to post at 10-1 and broke on the lead under Mario Pino. After holding the lead most of the way he yielded to Street Sense in the stretch to place second. Hard Spun then finished third in the Preakness and fourth in the Belmont Stakes.

By contrast Eight Belles won only once in five tries in her freshman year but four straight victories in 2008 convinced trainer Larry Jones to give the filly a chance to race against the boys in the Kentucky Derby. Eight Belles ran a monster race to finish second behind Big Brown but in her gallop out after the race she broke both ankles and heartbreakingly had to be euthanized on the track.

After Friesan Fire finished well back in 18th place in 2009, Porter’s Fox Hill Farm in Lexington, Kentucky produced a Horse of the Year in 2011 with Havre de Grace. Normandy Invasion ran out of the money in 4th in 2014 Porter was still without a Kentucky Derby winner - one of the few goals he has failed to achieve in racing.

DELAWARE HORSES

Harry JS. Harry JS was so intensely black he was said to sparkle as he trotted. Foaled in 1908 and named for his owner Harry J. Stoeckle, Harry JS began racing as a three year old and won five of five races when he came under the guidance of Delaware’s greatest horseman, Herman R. Tyson.

Tyson orchestrated Harry JS’s career on the Grand Circuit and on tracks up and down the east coast. In 1912 his ten-race mark was eight wins, one place and one show. As a six-year old he was forced to seven heats to win a race in Lexington and went the mile in 2:10 1/4 - the fastest time ever for a seventh heat.

In his final campaign in 1917 Harry JS set several world records and retired to stud acclaimed as the greatest 1/2 mile trotter ever. In 67 career races he won 35 and finished in the money 59 times. His lifetime earnings of $17,420 made him the leading trotter of his era. In all his years on the racetrack the great Harry JS was never known to break his gait. In 1925 Delaware’s most beloved horse dropped dead in his stall.

Adios Harry. In 1952 J. Howard Lyons made the long drive from his farm in Greenwood to a yearling sale in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania with his eye on a potential racehorse he had scouted for bloodlines and sound confirmation. While at the sale he was convinced to also purchase a colt bred by L.T. Hempt from the immortal pacer Adios. The youngster did not look promising and even after Lyons paid only $4200 the deal did not look like a bargain when the newly named Adios Harry turned out to have a temper and kicked at anything that moved.

He did make it to the racetrack, however, while his new stablemate never did. At two Harry flashed to the win in the Bloomsburg Fair Stake and at three he captured pacing’s biggest prize, the Little Brown Jug, by setting a three-heat record over the Delaware, Ohio fairgrounds oval. In 1955 Adios Harry became the fastest pacer ever when he blazed a 1:55 mile at Vernon Downs, New York. Like the four-minute human mile, the 1:55 mark was considered unobtainable for standardbreds. As it was, his record would stand for 16 years.

Adios Harry was just getting warmed up. By the time he was five years old he held 12 world pacing records and Sports Illustrated put him on the cover that year. When he retired in 1958 Adios Harry was the all-time money-winning pacer with $345,433.

It was always a family affair with Adios Harry. Howard did the training and his son Lucas often was in the bike. Many horsemen sniped that “Harry” could have done even better with professional connections but he had done very well, thank-you, as a family horse.

As such, Lyons decided not to sell Harry into syndication and brought him back to his Sugar Hill Farms to stand at stud. He sired 352 pacers, 26 of which ran sub-2:00 miles but none were as good as their dad. Harry lived out in the Lyons pasture until 1982 when he died at the advanced equine age of 31.

Silk Stockings. How many Delaware athletes have been profiled on 60 Minutes? Well, none of the two-legged variety but one equine superstar once got the treatment from Morley Safer, Mike Wallace and the boys. Silk Stockings was a special performer on the track with a special cause.

Ken and Claire Mazik purchased the New York-bred Silk Stockings as a yearling for $20,000. By the time she was three years old in 1975 the daughter of Most Happy Fella had developed into the greatest harness filly of all time. That year she set eight world records, including one for the most money ever won by a filly or mare in a single season, $336,312. And the bulk of those purses went to the Au Clair School for autistic children which the Maziks operated at St. Georges. And that’s what brought the camera crews from 60 Minutes to Delaware.

Trained and driven by Pres Burris of Smyrna, Silk Stockings peaked in the middle of 1975 when she won 12 straight races. In that stretch was a 1:58 mile at the Historic Track in Goshen, New York, the fastest time there by any horse in 137 years of racing; a world record 1:57.2 on a half-mile track; and a win in the New York Off-Track Betting Classic, the richest pace ever. Later that year she clipped a 1:55.2 in Syracuse, the second fastest mile ever paced by a female horse. For the year Silk Stockings won 15 of 24 starts and was voted Pacer of the Year by the United States Trotting Association. All for the autistic children of Delaware.

Miller’s Scout. It’s not that hard to make a million dollars - make $20,000 a year for 50 years and you’re a millionaire. That’s sort of the way Miller’s Scout, an unheralded pacer, became Delaware’s first million dollar horse. Miller’s Scout, a good horse with tremendous heart, made a living by chasing some of the sport’s greatest stars in the early 1980s. Eventually all those second place checks pushed him over the million-dollar mark.

In his 2-year old season in 1978 Miller’s Scout had 12 starts, winning twice and finishing second five times. He earned only $3,878. As a three-year old he finished in the money in 21 of 28 starts, winning eight times and bankrolling $46,664. It was during his 3-year old campaign that Miller’s Scout, foaled and reared in Ephrata, Pennsylvania, was purchased by a Delaware consortium including Bill Brooks, veteran standardbred owner and breeder and founder of the familiar armored car business, Baird Brittingham, a one-time president of the Thoroughbred Racing Association of North America, and Alfred du Pont Dent.

In 1980, as a four-year old, Miller’s Scout had his best year for wins with 12 in 32 starts. At the time his lifetime best was 1:58.1. Over the next 18 months the reliable pacer sliced his racing mark to 1:54.4 and he began touring in better company. The visits to the winner’s circle were less frequent but the checks were meatier.

On October 30, 1983 Miller’s Scout went to the post as a 50-1 shot in the $75,000 Blue Bonnets Challenge Pace in Montreal. The seven-year old pacer tracked Cam Fella, who was on his way to a world record 22nd consecutive victory, all the way to the wire. The $18,750 second place money raised his lifetime earnings to $1,016,026 - Delaware’s first equine millionaire.

EDDIE DAVIS

It has been a century-old tradition for Delawareans in Kent and Sussex Counties to take their best horses off their farms and test them on local harness tracks. This legacy of Delaware horsemen continues today at tracks along the East coast, even as the sport is dying in their home state.

Of the many drivers who have raced from Delaware none was ever as successful as Smyrna’s Eddie Davis. Davis, born in 1944, enjoyed his best years in the early 1980s when he was a top driver at Dover Downs, Brandywine Raceway and Liberty Bell Raceway. He was also a leading trainer during this time. To date he has won over 5500 races.

If there has been harness racing in the Delaware Valley, Eddie Davis has been the leading driver there.

Davis rated several horse to world records over the years. The highlight of his career came in 1981 when he nosed out 12-time world champion Herve Filion for the North American driving championship. Davis, the only Delawarean to ever win the title, won his 404th race on the final night of the year. Filion finished 1981 with 403 wins.

Davis won the driving title for the second time in 1983, maintaining a frenetic pace to the championship. On one day he won four races at Dover Downs and six at Liberty Bell, where he set a record for most wins at a single track in one year with 333. A typical Davis day would include an afternoon of driving at Freehold in New Jersey and a fast trip to Dover for a nighttime card as he concluded a successful drive to the title.

All that commuting turned Eddie Davis into the all-time winningest driver in the Delaware Valley - he rode into the winner’s circle 8,362 times.

TIC WILCUTTS

John Wilcutts was so small at Caesar Rodney High School in the 1930s that he was called “Tic.” After two years with the U.S. Army in the Pacific theater in World War II Wilcutts bought a discarded $700 pacer as a hobby. A horse named True Peggy took him to the winner’s circle often enough that Wilcutts became a professional driver.

From those humble beginnings he became the leading driver four times at Baltimore Raceway and twice at Laurel Raceway in Maryland, once at Rockingham Park in New Hampshire, once at Liberty Bell Park in Philadelphia and five times at Brandywine Raceway. He wound up his career with 1,755 race wins and nearly $5 million in purses.

Off the track Wilcutts owned Voodoo Hanover, a broodmare who gave birth to Albatross, one of the sport’s greatest champions. Wilcutts was voted into the Delaware Sports Hall of Fame in 1985.