Pre-1900 COURSES

Niagara On The Lake Golf Club (1875)

Golf came to Canada well before the United States. In November of 1873 a band of eight gentlemen armed with clubs and gutties imported from Scotland founded the Royal Montreal Golf club. The enthusiastic linksters played across nine holes on a course carved in a chunk of Frederick Law Olmsted's - the famous designer of New York's Central Park. Mont Royal Park known as Fletcher's Field. Six months later Royal Quebec Golf Club formed in Boischarel along the banks of the Montmorency River.

Both those original courses are gone today and the clubs have each relocated more than once. That leaves the honor of "North America's oldest golf course" to a pristine nine holes on the shore where the Niagara River spills into Lake Ontario. It was 1875 when John Geale Dickson laid out his course across from his home on John Street which he called Mississauga Links.

Dickson hailed from an old land-owning family in Galt, Ontario, near today's Cambridge. His uncle had emigrated to Upper Canada to manage the family interests and retired to Niagara in 1836. Subsequently, many of the handsome Victorian homes in Niagara were under title to the Dickson family. When the Niagara Golf Club officially organized in 1881 John's twin brother Robert was designated the first Captain.

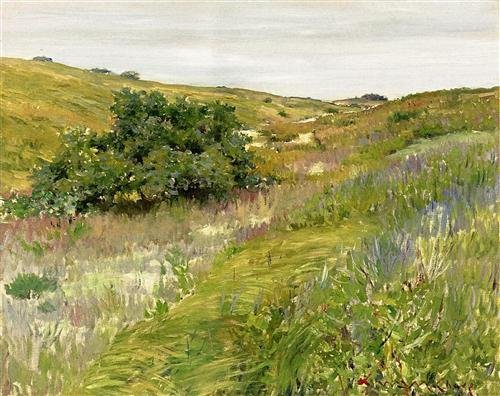

Golf was played in many of Frederick Law Olmsted's parks like Franklin Park in Boston

The Club was well regarded locally as a Toronto newspaper opined, "This golf course in Niagara is perhaps unsurpassed, and bids fair to become the St. Andrews of Canada. Its central position, ease of access by rail or steamer, and large area, combine to make it one of the best that could be selected for matches between other clubs and neutral ground."

The first hole, Straightaway, races out along the Niagara River towards a green tucked into the bosom of the ruins of Fort Mississauga, star-shaped earthworks that are a souvenir of the War of 1812. The first lighthouse constructed on the Great Lakes was located here in 1804 (the United States would not erect its first inland lighthouses until 1818) but the beacon was dismantled to make way for the brick fort in 1814. The fort saw no action and was not completed until after the Treaty of Ghent ended the conflict and established boundaries between Canada and United States.

The British Army kept Fort Mississauga in active duty until 1855 when it was turned over to the Canadian Army that used it as a summer training ground for many years. The masonry blockhouse remains standing as a National Historic Site and the public can reach the fort via a walking path - but golfers have the right of way on the property.

The Niagara On The Lake Golf Club has never hosted a major golfing competition but it does have the distinction of hosting the first-ever international tournament staged in North America. The Niagara International took place from September 5-7, 1895 and was won by Charles Blair Macdonald. Macdonald was on his way to Newport Golf Club to compete in the first United States Amateur Championship, which he would win 12 and 11 over Charles Sands in the finals, and might not have made the Niagara International if the Amateur had not been postponed due to a conflict with the America's Cup yacht races. Such a busy life for Gilded Age sportsmen. Macdonald also won perhaps the first ever Long Drive Championship when he spanked a shot 179 yards, one foot and six inches in a competition on the first hole.

Today Niagara On The Lake Golf Club at more than 140 years old is open for public play. While some holes have been lengthened to create a regulation 3,104-yard par 36 course, the routing and much of the fairways remain in their original state. The green on #8 Cinch has never been altered in its lifetime. In fact, Niagara On The Lake give little quarter to modernity. Designed in the age of pony carts the parking lot holds scarcely a dozen cars. There is a drop-off for your golf clubs but then you need to drive into town and scrounge an available parking space - so arrive early for your tee time.

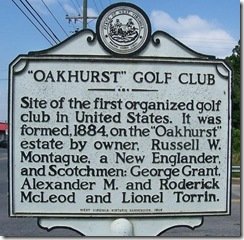

Oakhurst Golf Links (1884)

The United States is home to about half of the world's 35,000 golf courses and this nine-holer in the folds of the Allegheny Mountains is considered the oldest. The little town of White Sulphur Springs gained a reputation through the 19th century as the "Queen of the Watering Places" where wealthy Virginia planters came in the summer to escape the humidity of the coastal plains. It was word of these healing waters that attracted the attention of a 24-year old Harvard-educated lawyer from Massachusetts named Russell Wortley Montague in 1876.

Montague bought property two miles northeast of White Sulphur Springs where Dry Creek had cut a narrow valley on its journey to the Green Brier River and erected a simple Colonial Revival-style two-story farmhouse that he and his wife Harriet used mostly in the summer. The story goes that in 1884 a transplanted Scot named George Grant wanted to prepare for the visit of his cousin, an owner of a tea plantation in Sri Lanka named Lionel Torrin, by laying out an informal golf course in a pasture on the Montague farm.

If the sign says it, it must be true...

Montague had spent time traveling in England and Scotland and had played golf, reputedly at St. Andrews. Torrin was reportedly a golfer of some repute and the three men tackled the project with the aid of two more neighbors, Scotsmen Alexander and Roderick McIntosh McLeod. The five men roughed out a rudimentary course across 35 acres in the creek valley which began near the main house and played across a gravel road which naturally became known as "The Road Hole." Heavy cast iron sleeves were driven into the native pasture grass as cups.

George Donaldson, a native of Scotland who ran a local lumber yard joined the original five golfers and the membership of the Oakhurst Links was set. The early links enthusiasts played regularly and competed for the Oakhurst Links Challenge Medal, emblazoned with the motto "Far and Sure" on one side. It is considered the earliest match play in America. By the early 1890s all but Montague and Donaldson had moved back to the British Isles and the course received less and less play. By 1912 Oakhurst returned to pastureland.

Russell Montague died in his 93rd year in 1945 and his children inherited the property. Lewis Keller bought the property in 1959, when he learned of its history as a golf course. The land had never been tilled and Keller, a golfer and friend of Sam Snead, could make out the ghosts of tees and green sites where his horses grazed. In 1994 Keller hooked up with golf architect Bob Cupp who became enchanted with the prospect of reviving the 110-year old course.

Cupp was able to use old magazine articles to decipher the general route of play and used soil tests to for clues about bunkers and greens. Much was guesswork but none of Cupp's restoration - all done by hand and shovel - could be said to have altered the historical accuracy of the course. In 1995 Keller re-opened the course for public play. Oakhurst Links played to a par of 37 across 2,235 yards. The catch was that players were required to rent and use replica hickory clubs and hit only gutta-percha balls similar to ones Montague and his friend played with a century before. Tee balls were struck from mounds formed with a pinch of wet sand.

After a half-century as steward of Oakhurst, Lewis Keller sold the golf course, now on the National Register of Historic Places, to the neighboring Greenbrier resort. The prohibition against modern equipment remains in effect and players - often sporting period attire - still tour Oakhurst Links as if playing America's oldest golf course.

Foxburg Country Club (1887)

Foxburg Country Club traces its roots all the way back to George Fox in northern England in the 1600s whose Christian leadership led to the formation of the Society of Friends, better known as the Quakers. When America’s number one Quaker, William Penn sailed to America in 1682 to claim lands owed to him from a debt between King Charles II and his father, members of the Fox family quickly followed. In 1796 Samuel Mickle Fox purchased land warrants totaling 6,600 acres along the Allegheny River from the Penn family in the western wilderness of Pennsylvania.

Fast forward another century to Joseph Mickle Fox, Samuel’s great grandson. A member of Philadelphia aristocracy, Joseph Fox was a member of the Merion Cricket Club which embarked to Great Britain to participate in a series of international matches in 1884. “The Gentlemen of Philadelphia” acquitted themselves well, including a match versus Scotland at fabled Raeburn Place in Scotland where the Americans lost by only five wickets.

Afterwards, Fox visited St. Andrews where Tom Morris gave him an introduction to this different type of field game. Morris began at his native St. Andrews as an apprentice to Allan Robertson, considered golf’s first professional. According to legend the two were never bested in matches across Scotland. Robertson did a bustling trade in “featherie” golf balls and had a falling out with Morris when his protege embraced the new gutta percha golf balls. Morris left for Prestwick where he presided over the first Open Championship - which he would win four times, in 1860. He returned to St. Andrews in 1865 and stayed until 1904 and he sent Joseph Fox back to America with a supply of balls and clubs from his shop near the 18th green of the Old Course.

Upon returning to Pennsylvania Fox began using his new toys on the family’s RiverStone Estate. When others became interested in his game he sent away for more clubs and balls. The group formed the Foxburg Country Club in 1887, using a course laid out on pastureland Fox provided free of charge on an escarpment above the Clarion and Allegheny rivers. At first there were just five holes, with flower pots used for holes. By 1888 there were a full nine holes and that course, with some remodeling, has been played ever since.

The first great golf trick shot artist - Joe Kirkwood - honed his skills in the Australian Outback. He was a unanimous choice for the American Golf Hall of Fame.

Today the American Golf Hall of Fame Museum stuffed with mementoes from golf’s early days resides on the second floor of the Foxburg clubhouse. The handsome Adirondack-styled building was constructed in 1912 as a private residence by the prestigious architectural firm of Goldwyn Starret and Charles Edmund Van Vleck, the nation’s pre-eminent designers of upscale department stores. The club picked it up for $5,000 in 1942.

Spreading out in the valley below, the nine-hole Foxburg course plays to 2,580 yards as it winds through ancient Pennsylvania hardwood forests. The small greens are testament to their 19th century beginnings as America’s oldest continually operating golf course open to the public.

Shinnecock Hills Golf Club (1891)

Among the pioneering American golf clubs the history of Shinnecock Hills is more murky than most. There are questions regarding who should get credit for bringing golf to Southampton, Long Island - the sister of the proprietor of the Shinnecock Inn who encountered the game on a trip to Scotland or a group of New York City businessmen who discovered the game on a vacation to the south of France. Or perhaps a bit of both.

There is confusion as to who actually built the first course - the leading candidates were both Scots named Willie, and in the 19th century it was generally assumed that any Scotsman in America named Willie was a golf expert. As best as can be gleaned from contemporary accounts, William D. Davis was recruited from the Royal Montreal Golf Club in 1891 to come to eastern Long Island to lay out a golf course an teach curious New Yorkers how to play.

Shinnecock Hills, as depicted by impressionist artist William Merritt Chase in the 1890s, was just waiting for a golf course to be laid upon the landscape.

Davis actually laid out two courses - a nine-holer for men and a shorter, supposedly easier track for women. Whatever the true story, there seems little doubt that the club was the first to embrace women's membership. Of the 44 founding members, 12 were women. It is no surprise that Shinnecock members dominated the first women's national championships. Lucy Barnes won the inaugural United States Women's Amateur in 1895 by turning back a field of thirteen with a course record 132 at the Meadow Brook Club down the road in Hempstead.

The following year 16-year old Beatrix Hoyt, the granddaughter of Abraham Lincoln's Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase, won the first of three straight championships. The New York Sun gushed that Hoyt's game was, "superior in quality of to any of our men."

There is also no dispute that the club takes its name from the Shinnecock Indian Nation whose ancestral lands included all of modern-day Rhode Island, most of Connecticut and a large swath of Massachusetts, in addition to eastern Long Island. The tribe hardly viewed the name as a tribute - the Shinnecock peoples have always disputed legal ownership of the land and claim the golf course was constructed on a tribal burial ground.

Meanwhile Stanford White, the go-to architect of the rich and famous in America's Gilded Age, set to work on the clubhouse in 1892. There had never been a building constructed solely for a golf club and White set the standard for every clubhouse that would follow. White sited his sprawling gray-shingle creation on the highest point on the property overlooking the golf course. He balanced its comfortable, inviting role as a "house" with the propriety of its members by supporting the overhanging roofs of the verandas with imposing white Doric columns.

Davis soon departed, leaving the new Shinnecock members to fend for themselves. In 1893 Willie Dunn, from a prominent Scottish family, arrived at Shinnecock to take charge of golf operations. Dunn expanded the course to 12 holes, keeping some of the original holes in his new routing. Meanwhile, Shinnecock Hills incorporated in 1894, becoming the first American club to do so.

Shinnecock Hills hosted the second United States Open in 1896, won by Scottish pro James Foulis, and the 1900 United States Women's Amateur (Hoyt lost in the semi-finals and abruptly quit golf forever without explanation). And that was it for national tournaments as Shinnecock Hills retreated from the public eye for over 75 years, known only to golf aficionados and architecture buffs.

The Shinnecock Hills clubhouse became the prototype for American golf clubs everywhere.

Shinnecock took its first tentative steps back into the golfing sunlight by hosting the Walker Cup in 1977. The United State Golf Association then awarded the 1986 United States Open to Shinnecock Hills, promising that golf fans would discover America's truest golf links and one of the country's finest courses.

What golf fans saw when the Shinnecock gates swung open was a completely new course from that which had hosted the Open 90 years before. In 1927, New York State Route 27 sliced right through the club property and the club's insurance rates soared due to the increased traffic crossings of the golfers. The portion of the course south of the road was abandoned and additional property purchased on the north side.

The project for the new course was turned over to Philadelphia architect William Flynn. Flynn found the new land superior to that sacrificed and he took care to retain the rugged, natural look. The undulations of Shinnecock seem to flow seamlessly from one hole to another. The overhauled Shinnecock Hills opened in 1931 and was essentially the same course that greeted the world's best golfers in 1986.

The results were even better than hoped for. Shinnecock Hills gave little quarter to the competitors as Raymond Floyd won with a 279 total, one under par. The course was instantly acclaimed as one of the elite tests of championship golf in America and the U.S. Open has returned every decade since - 1995 (Corey Pavin winning), 2004 (Retief Goosen winning) and 2018.

Furthermore, America fell in love with links golf. Treeless courses built nowhere the near the ocean (sandy turf being the prerequisite for a links course) billed themselves as "links courses." Classic courses that had been built on treeless land embarked on programs to remove thousands of trees that had been planted by greens committees over the decades. The result is that Shinnecock Hills has emerged as the most revered of the original five founding USGA clubs.

Downers Grove Golf Club (1892)

Chicago of the 1860s was no place for a young boy of privilege to get a proper education. So Charles Blair Macdonald, whose family owned larges swaths of upstate New York, was sent away from the muddy streets and roaming swine to the University of St. Andrews in Scotland when he was 16 years old in 1871. Even then, St. Andrews was the cradle of golf. But Macdonald was not impressed by the game he had never heard of. As he wrote in his memoir, Scotland’s Gift: How America Discovered Golf, “It seemed to me a form of tiddle-de-winks, stupid and silly.”

But grandfather Macdonald was a member of the Royal and Ancient Golf Club of St. Andrews and impertinent Charles was nonetheless sent to the resident pro, Tom Morris for instruction in the game. One of the young Chicagoan’s frequent playing partners was Morris’ son who was the Tiger Woods of his day. “Young” Tom Morris won his first Open Championship at the age of 17 in 1868 and would win three more times before dying of “a broken heart” before his 25th birthday after his wife died in childbirth. Properly indoctrinated by Old Tom Morris and Young Tom Morris, Macdonald returned to America in 1874 totally besotted by the game of golf.

The imperious Charles Blair Macdonald cast a large shadow across early American golf.

Back in Chicago there was little time for frivolous pursuits. The city was recovering from the Great Chicago Fire of 1871 and the country was limping back to life after the Panic of 1873. Macdonald’s career in finance gave him little time to escape from his office in the Board of Trade. Even if he could, there were no golf courses in the United States. As Macdonald lamented, “It was surely the Dark Ages for me.”

It would be the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893, known familiarly as the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893, that would lift the shroud. To amp up the “worldliness” of the transportation hub Macdonald was enlisted in 1892 to stake out seven golf holes across the baronial lawns surrounding the Gilded Age mansion of Charles Benjamin Farwell, one of the bankers most responsible for the rise of Chicago and only recently back from a stint in Washington as a United States senator. It was not much of a golf course, but it stirred Macdonald’s long-subdued passions for the sport.

In the summer of 1892 he set out to build a right and proper golf links. Macdonald solicited $10 from associates and raised a few hundred dollars to buy some farmland west of Chicago in the village of Belmont. Macdonald was the only golfer he knew and he designed his course to suit his game; he always battled a nasty left-to-right slice and so the nine holes were routed clockwise with out-of-bounds to the left on seven holes. Macdonald was pleased enough with his efforts that he added an additional nine holes the following spring to create the first 18-hole golf course in America. On July 18, 1893 the Chicago Golf Club was chartered.

By this time Macdonald had forged a clear vision for what he wanted a golfing experience to be. He no longer just wanted a place to play golf - he wanted a facility to rival the original links in Great Britain. He engineered the financing for 200 acres of farmland in Wheaton - a 30 mile train ride from the Chicago Loop - and built the first 18-hole golf course in America designed as such. He was knee-deep in every aspect of its construction, recruited the membership and erected a stately house overlooking the new Chicago Golf Club for himself.

Macdonald’s original course was soon a distant memory - or, if the aristocratic founder had his way, completely forgotten. The pioneering track did not disappear and reverted back to the original nine holes. Herbert J. Tweedie organized the Belmont Golf Club on the site and Macdonald made sure there was no confusion concerning the two clubs. As he wrote in his autobiography, “None of the members of the Chicago Golf Club were members of the Belmont Golf Club, and the clubs are not the slightest degree identical.”

Despite the disavowment of its pedigree by its founder, the Belmont Golf Club trundled on until 1968 when it was purchased by the Downers Grove Park District. Play continues 125 years after its opening and features of the original course can still be seen on holes 2, 4, 7, 8 & 9. Downers Grove Golf Club operates as a true municipal course open to all who want to play. The Chicago Golf Club thrives as well and is considered one of the handful of most exclusive country clubs in the world. Just as Charles Blair Macdonald would have wanted it.

Newport Golf Club (1893)

From its origins in America golf was the ultimate "rich man's game," mostly since the men introducing the sport were wealthy enough to have traveled to Scotland to discover it. It was only a matter of time before golf made its way to the ultimate bastion of the Gilded Age in the 1890s - Newport, Rhode Island.

The man who provided the introduction to the industrial elite was Theodore Havemeyer, who learned the game while vacationing in Pau, a mountain resort in the Pyrenees in southwestern France where the first golf course on the Continent had been constructed. Havemeyer's fortune came from sugar. In 1802 brothers William and Frederick Havemeyer sailed from London to Manhattan after having spent a little time working in a cane sugar refinery in London. After starting their sugar business the Havemeyers relocated to Brooklyn where they found "good deep water, plenty of labor, and space to build." By the end of the 19th century the "Sugar Kings" controlled 80% of the sugar refined in America and "white gold" produced in great Romanesque Revival brick factories on the Brooklyn waterfront alone represented 40% of all the manufactured products in the city.

Whitney Warren's sketch for the Newport clubhouse.

Until he stumbled upon golf Theodore's main diversion was breeding sheep, hogs and Jersey cows on his 600-acre spread In New Jersey. But beginning in 1890 Havemeyer and a few friends began renting 44.4 acres of pastureland on Brenton Point overlooking the Atlantic Ocean a short distance from the family estate on Bellevue Avenue. A rough nine holes was laid out that crisscrossed the stonewalls on Elizabeth Gammell's centuries-old farm.

After three years the men decided it was time for a right and proper golf course. They recruited Willie Davis, who hailed from Royal Liverpool on the west coast of England, for the job. Davis emigrated to Canada in 1881 at the age of 18 to become the first golf professional on this side of the Atlantic Ocean at the Royal Montreal Golf Club. He designed the golf course on the Ile de Montreal and a decade later laid out the first 12 holes of Shinnecock Golf Club.

Davis, whose duties included clubmaking for the Newport golfers - both men and women - laid out nine holes on the club's new property, 140 acres owned by Mary A. King that was known as Rocky Farm. The name came honestly as Davis discovered that although Newport was hard by the sea the soil was composed of clay and not sand, as a true links demanded. Nonetheless, the promontory above the Atlantic Ocean was fine golfing ground for the new Newport Golf Club that was officially incorporated on March 1, 1893.

This being Newport, one of the first orders of business was erecting a suitably impressive clubhouse, along with getting a polo field and trotting track up and running. A design competition was staged and submissions poured in from the most famous architects of the day. But the winner was a 30-year old unknown who belonged to no prestigious firm and had just returned from a nine-year sojourn abroad. But Whitney Warren was one of Newport's own and knew his way around the typical Bellevue Avenue mansion. His elegant French Chateauesque scheme, executed in an embracing Y-shaped design, carried the day. When the clubhouse was completed in 1895 after $47,139 had been spent (and another $7,872 for a caddie house and stables and $6,608 for furnishings, the New York Times rendered its judgement, "It stood supreme for magnificence among golf clubs, not only in America, but in the world."

Club president Havemeyer next turned his attention to golf, of which he was equally proud. In addition to Davis' nine-hole course he had also put together a six-hole layout for children and newcomers tot he game. Havemeyer put word out that Newport would be hosting the first-ever American national championship on September 10th and 11th, 1894, consisting of 36 holes of stroke play across two days. The event attracted 20 competitors, eleven of whom packed up their clubs and went home after the first day after high scores.

President John Kennedy and Washington Post editor Ben Bradlee enjoy a round of golf at Newport while Jackie Kennedy and Jean Bradlee look on.

Chicago Country Club founder Charles Blair MacDonald considered himself America's best player and he fully expected to win inaugural golf tournament but was thwarted by an unfortunate encounter with the stone wall on number eight. MacDonald blustered that the Newport event could hardly be considered a "championship" since it was not contested at match play and, incidentally, stone walls have no place on golf courses (although revered links in Scotland such as North Berwick feature the ancient obstacle). A month later the St. Andrew's Club staged another national championship, this time at match play. After MacDonald lost in the finals, he again spat that this could not be a "national championship" since it was sponsored by a single golf club.

What was clearly needed was a national golf organization and thus the United States Golf Association came into being at the Calumet Club in New York City on December 22, 1894 with five clubs represented: the Chicago Golf Club, The Country Club, Shinnecock Hills, St. Andrew's Golf Club and Newport Golf Club. The genial Havemeyer was selected to be the first president and the Association's charge was to organize national championships, establish uniform rules for the game in America and administer those rules.

That year's tournaments would be reprised in 1895 as the United States Amateur with a match play format and the United States Open, held a day later for professionals and amateurs, at stroke play. Newport Golf Club, the course of the president, was chosen to hold both events in the fall. To insure the new USGA was a success Havemeyer picked up the expenses of all contestants coming to Newport.

When the United States Amateur teed off the new governing body was faed with an immediate challenge. Richard Peters showed up for his match against Reverend Dr. Rainsford with a billiard cue to handle his greenswork. Tournament officials made no ruling but Peters holstered the cue after the first hole when Rainsford requested he not use it again. MacDonald this time indeed triumphed in the U.S. Amateur, dispatching tennis player and future Olympian Charles Sands of St. Andrew's 12 and 10 in the 36-hole final. Horace Rawlins was an unlikely winner of the first U.S. Open.

The events were a success and, of course, have been held ever since - but never again at Newport Golf Club for another century. In 1897 Davis laid out another nine holes to bring the course to a regulation eighteen but the low-lying ground proved mostly unsuitable for golf. Havemeyer died unexpectedly at the age of 57 from stomach troubles in in his New York City home in 1897 in and the club lost direction. Shortly thereafter the membership voted itself out of existence and merged assets with the Newport Country Club. Additional land was purchased and in 1923 A.W. Tillinghast interwove seven new holes into Willie Davis' historic original nine holes to create a new routing for the historic course. Meanwhile Newport and its one percent of the one percent membership retreated from public view.

The public would only glimpse the historic course again in 1995 when the Amateur returned on the centennial anniversary of that first tournament. Tiger Woods, the greatest player of his generation, won the second of three consecutive national amateur titles - and the trophy that bears Theodore Havemeyer's name. In 2006, Newport Golf Club hosted the United States Womens Open and Annika Sorenstam, the greatest player of her generation, finished on top.

The Country Club (1893)

When deciphering the early history of American golf it is necessary to parse the definitions of words such as "continuous" and "oldest" and "original." So Saint Andrew's Golf Club in Hastings-on-Hudson gets the nod as "America's oldest golf club" since golf has been played continuously by its members since the winter of 1888 when 47-year old Scotsman John Reid and his pals first began banging gutta-percha balls around three holes laid out in a pasture. The favorite part of the course for the fellows was a gnarled old apple tree that served as the "19th hole" for partaking in rounds of fine scotch whiskey. On November 14, 1888 in a meeting in the Reid home the "Apple Tree Gang" formally started a golf club, borrowing the name from the home of golf and adding an apostrophe.

By that time The Country Club had already been around for six years in Brookline, Massachusetts, outside of Boston. But there was no golf being played in Brookline. So it hangs on to the tag of "oldest country club in America." It was truly a "club in the country," organized for outdoor pursuits such as horseback riding in the summer and ice skating in the winter. When the idea took hold to play golf it was 1893 and three members were recruited to lay out six holes. The horse people were none too pleased with the development, especially since part of the course meandered across the trotting track.

But the golfing members had been captivated by the game. They brought over one of the first foreign golf professional golfers to the United States, Willie Campbell, to head their nascent program. Campbell had finished in the top ten in eight consecutive appearances in the Open Championship in the 1880s and was the most accomplished player in America. He quickly set about expanding the course to nine holes as the equestrians fumed.

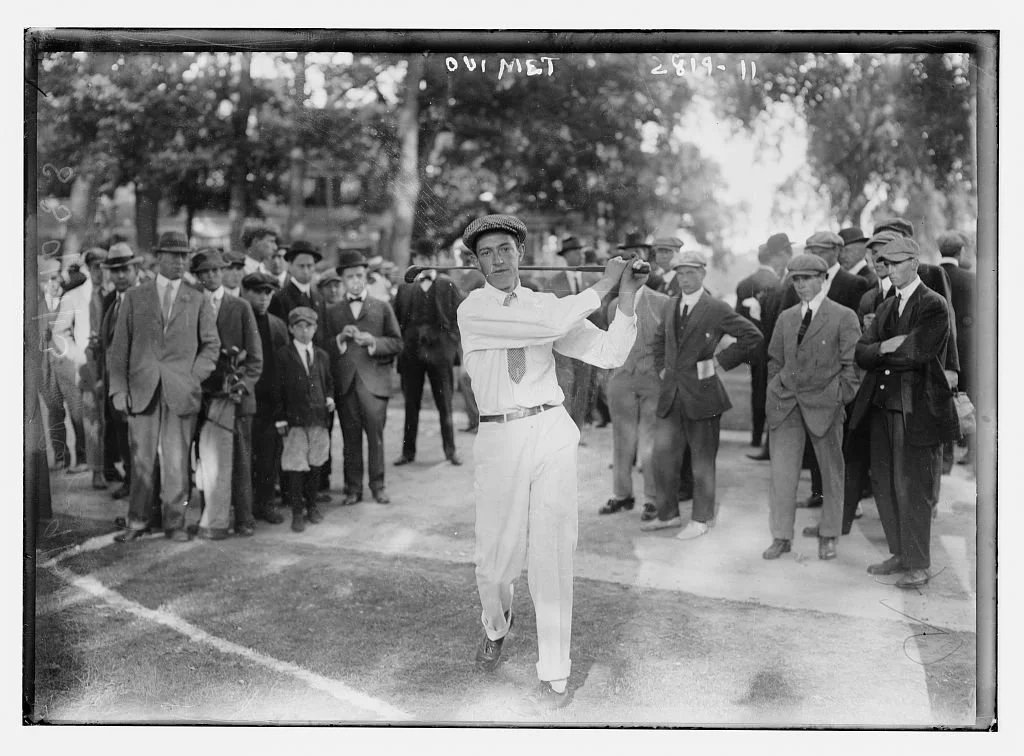

Brookline hero Francis Ouimet hits away in front of the local gallery.

The opposition from the headstrong horse crowd about the future of The Country Club was vociferous enough that Campbell departed in 1896 for the Myopia Hunt Club in nearby South Hamilton. Nonetheless, the course was expanded to 18 holes by 1899 and lengthened in 1902 with the arrival of the energetic wound-rubber Haskell golf ball. All of the changes were executed by club members.

It was these 18 holes that became the first famous golf course in America. The occasion was the 1913 United States Open. By this time The Country Club had hosted the United States Women's Amateur (won by New Jersey ace and two-time champion Genevieve Hecker in 1902) and the United States Amateur (won by William C. Fownes, Jr., the son of the founder of Oakmont Country Club, in 1910. But this was the first time the Brookline course had been tabbed to hold the U.S. Open in the almost two decades since the founding of the USGA in 1895. Of the five founding members, The Country Club was the fourth to host the championship; Saint Andrews would never do so.

At the time, the golf world was still very much ruled by British golfers. The first native-born American to win the U.S. Open had been Johnny McDermott, a Philadelphia golfer who dropped out of high school to play professional golf, only two years before in 1911. McDermott won again the next year at the Country Club of Buffalo so he had two Open titles before his 21st birthday.

But in the weeks approaching the U.S. Open at the Country Club in 1913 all the talks was about two British stars planning to compete. Harry Vardon, the greatest golfer in the world with five Open Championships to his credit and another to still come, was making only his second appearance in the United States Open. The first had been back in 1900 at the Chicago Golf Club and Vardon had won that tournament by two strokes.

Vardon would be joined in the 1913 U.S. Open field by one of his great rivals, Ted Ray. Known for his prodigious hitting off the tee, Ray was the defending Open Champion and had never competed in the United States Open. The two stars were on a two-month promotional tour of North America financed by Lord Alfred Harmsworth, a British newspaper mogul and the Rupert Murdoch of his day. Vardon and Ray played exhibition matches against the continent's top players and the U.S. open was slated to be their crowning denouement.

The first two rounds were held on Thursday, September 18. Vardon played indifferently in the morning and finished with a two-over par 75. Ray was even more baffled by the unfamiliar Brookline course and posted a 79. But he roared back in the afternoon to shoot a course record 70. Vardon too played sub-par golf and had a two-stroke lead after the first day of play.

Conditions were harsher for the two rounds scheduled for Friday and at the end of the morning play the two British stars found themselves tied for the lead with an unknown 20-year old American amateur, Francis Ouimet. Ouimet grew up in a working class immigrant household across the street from The Country Club. Young Francis learned his golf by sneaking barefooted onto the 17th hole and later in rounds at Franklin Park, using balls and clubs scavenged from The Country Club caddy yard.

Ouimet had won the Massachusetts Amateur championship earlier in the year but had no plans to enter the U.S. Open. Only a personal request from USGA president Robert Watson, hoping a local amateur might juice the gate, enticed him to play in the national event. Watson even entered Ouimet without his knowledge. His opening tee shot seemed to bear Ouimet's reservations out - the topped ball scarcely rolled 40 yards. But Oiumet ultimately fashioned a pair of 74s to go with his opening 77 to join the British greats at the top of the leaderboard.

The trio would remain tied at the end of 72 holes after shooting identical 79s in the final round. But the symmetry was not that clean. Vardon and Ray finished first and were in the gallery as Ouimet finished in the darkening afternoon. He converted a critical birdie on the familiar 17th hole and scrambled for a par on the 410-yard home hole to earn his way into an 18-hole playoff on Saturday.

Harry Vardon, Francis Ouimet and Ted Ray at the 1913 U.S. Open.

The next day dawned with a steady drizzle that would not let up all day. The golf was more of the same with all three players reaching the turn in 38 strokes. Ouimet forged an early advantage on the inward nine and again knocked in a birdie putt on the 17th hole to give him a working margin of three strokes with one hole. A solid par got him to the house in 72, five strokes better than Vardon, who claimed the $300 top prize by one over Ray.

America had its first golf hero. Francis Ouimet was carried off the 18th green by some of the estimated 10,000 spectators in attendance. His achievement was splashed on front pages of newspapers around the country. A photograph of Ouimet and his 10-year old caddy, Eddie Lowery, became the first famous photo in golf. A statue of the photograph was cast and dedicated on the site, although it has since been moved to the Robert T. Lynch Municipal Golf Course next door. The account of Ouimet's triumph would be told in books and a Walt Disney Movie, The Greatest Game Ever Played, released in 2005.

Francis Ouimet was not a member of The Country Club when he won the United States Open there. He had joined Woodland Golf Club in Newton as a junior member in 1910, ponying up $25 borrowed from his mother to cover the dues so he could have a club affiliation to qualify for tournament play. He was a Woodland member until his death in 1967, representing the club as he won two United States Amateur championships, six Massachusetts Amateur titles and a Massachusetts Open. He would only play in five more U.S. Opens, with a tie for third in 1925 being his best future effort.

In 1951 Ouimet became the first American named a captain of the Royal and Ancient Golf Club of St. Andrews, Scotland. Two years after that he was finally made an honorary member for life of The Country Club, joining pioneering tennis great Hazel Wightman as the only such honoree. It was never a tribute that Oiumet had considered his due. During the club's golden anniversary celebration in 1932 he said, "“To me, the property around here is hallowed. The grass grows greener, the trees bloom better, there is even warmth in the rocks you see around here. And I don’t know, gentlemen, but somehow or another the sun seems to shine brighter on The Country Club than on any other place I have seen.”

Since Ouimet's landmark 1913 victory the spotlight has returned to The Country Club time and again. But first, Massachusetts-born William Flynn was recruited in 1927 to expand the golf facilities to three nine-hole loops by adding an additional nine holes and redesigning three others. The result was that the original six holes disappeared forever and the new holes were intermingled with the existing championship course.

The upshot of the renovations is that the existing front nine emerged intact as the Clyde nine with new greens and bunkers; the back nine was altered and infused with new holes and given the name Squirrel; and Flynn's third nine was called Primrose. The championship course was a mixture that has become known as the Composite Course.

That is the course television viewers are familiar with as The Country Club has hosted a half dozen United States Amateur championships and U.S. Opens in 1963 and 1988. Most notoriously the club hosted the 1999 Ryder Cup which became known at the "Battle of Brookline" as the United States players and fans zealously celebrated a comeback victory on the final day of Singles play. As The Country Club had been the site for the rupturing of the balance of golf power between Great Britain and the United States in 1913, the crowd behavior marked another seismic shift in golf from the English viewpoint. Long-time commentator Alistair Cooke heralded the exuberant celebrations as the arrival of the golf hooligan in "a date that will live in infamy."

That is quite a bit of history for a golf course that was cobbled together by members at a place where the finest pedigrees belonged to the horses. It is no coincidence that the handsome horse stables with its Greek Revival facade stands proudly beside the main clubhouse.

Myopia Hunt Club (1894)

Frederick O. Prince, an active member of the Whig Party and future mayor of Boston, had four athletic sons who played baseball for Harvard University in the 1870s. All four also happened to wear glasses and when they formed a barnstorming baseball team manager W. Delano Sanborn dubbed the team the Myopia Nine, in honor of the five players who used spectacles to correct their nearsightedness. In 1875 when the Princes started a sporting club for baseball, tennis, water sports and equestrian activities they took the name and it became the Myopia Hunt club. No doubt the foxes of Massachusetts were relieved by their pursuers handicap.

In 1894 R.M. “Bud” Appleton suggested that golf be undertaken at Myopia. Fortunately Appleton was also the Master of the Hounds at the club which helped appease the horsemen who were not nearly so enthusiastic. Appleton had once laid out some holes on the family arm started by Thomas Appleton in 1638, and is today the oldest continually operating farm in America, and he set out with fellow members Squire Merrill and A.P. Gardner to lay out a crude nine holes. The course was ready on June 1, 1894 and response was so enthusiastic that Myopia staged a tournament on June 18. The winner was 39-year old Herbert Leeds, a Boston sportsman who had also once played baseball for Harvard. Leeds went around the course in 58 and 54.

The Harvard nine that gave the Myopia Hunt Club its name - sans eyeglasses.

Leeds took an interest in the club and lobbied the membership to make upgrades to the course. They agreed and handed him the job. Thus was born one of golf’s great autocrats. Herbert Corey Leeds would spend the last thirty-plus years of his life molding and experimenting with the Myopia layout to create one of the most talked about course in early American golf. His initial efforts were so well-received that Myopia Hunt Club hosted the U.S. Open in 1898. And again in 1901, 1905 and 1908.

When British stars Harry Vardon and J.H. Taylor toured the course in 1900 Taylor set a course record of 78. Vardon did not have quite such a jolly day. He would write later in his autobiography, My Golfing Life, “While most American courses suffered from a lack of bunkers, Myopia was unfortunately rather spoiled by an excess of them.” There were more than 200 of them and members joked that Leeds carried white pebbles in his pocket and whenever he saw a player hit a good approach shot to a green he would drop a few stones on the spot and a bunker would soon appear there.

But it was not Leeds’ bunkers for which Myopia was famous, it was his “chocolate drops.” Like much of the New England countryside the property was crisscrossed by stone walls. Rather than incur the expense of carting the stones off the premises Leeds instead gathered the stones in piles and planted wild grasses on top. The result made Myopia Hunt Club one of the stoutest challenges in American golf. The three highest winning scores in U.S. Open history - 331, 328 and 322 - were all posted on Herbert Leeds’ course.

Herbert Corey Leeds spent more than three decades shaping the Myopia Hunt course.

Leeds died in 1930 and with the onset of the Great Depression and then World War II, the Myopia course floundered. By the 1970s fewer than two dozen rounds a day were being played - the golf season ended on Labor Day. When new professional Bill Safrin showed up for work from Philadelphia he found a bare golf shop with no merchandise. One of the members assured him it was of no concern since “nobody makes the trek up to the pro shop anyway.”

Safrin has spent over thirty years rebuilding the golf culture at Myopia, re-establishing the course as a jewel of classic American golf architecture. The USGA has not returned since 1908 but has been courting the membership to host a tournament without success for over twenty years. Most recently the 2020 Women’s U.S. Open was rejected. Until the powers-that-be at Myopia relent this slice of 19th century golf that was the first American course to be compared to its long-toothed British counterparts, will not be enjoyed by the 21st century public.

Country Club of Rochester (1895)

Few courses can match the glistening roster of major championship as Oak Hill in Rochester, New York - three U.S. Opens, three PGA Championships, two U.S. Amateurs and a Ryder Cup. As a test of championship golf Oak Hill has no peer. But it doesn’t have Walter Hagen.

Walter Charles Hagen was born in a two-story farmhouse overlooking Allens Creek on December 21, 1892. His father was a millwright who picked up extra money blacksmithing for the New York Central Railroad whose tracks ran right by the house. His mother took care of Walter and his four sisters.

The Country Club of Rochester as it looked in Walter Hagen's Day.

Three years later members of the Genesee Valley Club bought some land on Brighton Road to build a golf course. The social club had been started by Hobart Ford Atkinson, who was born on one of Colonel Nathaniel Rochester’s original lots in the village of Rochesterville in 1825. When the town’s leaders met in Atkinson’s bank sixty years alter they agreed there were four things that were mandatory in a club: 1) a reading room with the most current periodicals; 2) a library; 3) a restaurant with simple food, properly prepared and convenient; and 4) a supply of wines, liquors and cigars.

By 1895 golf was added to the list and the Hagens could watch the progress of the course from their yard. The family was not a part of the Genesee Valley Club when the course opened but Walter had developed an interest in the game anyway. When he was five years old he could be seen playing golf in the family’s cow pasture, although much of his day was spent convincing his bovine grounds crew to munch grass in one area to create a putting green.

By the age of seven Hagen was a regular at the Country Club of Rochester, shagging golf balls for members. After he joined the caddy ranks his athleticism attracted the attention of the club professional Andy Christie who provided young Walter instruction. He progressed so quickly that the members had no objection to allowing Hagen to use the course for practice rounds.

Walter Hagen was a golfing unknown when he showed up for the 1913 U.S. Open in Brookline.

Hagen’s lot at the club improved steadily, He was made caddie master and then assistant professional. In 1912 he hoped to enter the U.S. Open that was held at the nearby Country Club of Buffalo but Christy would not allow him the time off. But he took Hagen to Buffalo for a practice round to introduce him to competition beyond Rochester. Hagen was not awed by big-time golf and shot a 73 before taking the disappointing train ride back to the Rochester golf shop.

Hagen’s restlessness to begin a career in professional golf was exacerbated when Johnny McDermott, who was only one year older than him and whose life mirrored his own, won his second consecutive U.S. Open in Buffalo. McDermott grew up in Philadelphia. He caddied at Aronimink Golf Club and learned to play banging balls in the apple orchard next to the exclusive course.

McDermott worked in Philadelphia area shops and won the Philadelphia Open - a big tournament - in 1910 when he was 18 years old. Later in the summer he lost the U.S. Open in a three-way playoff. In 1911 McDermott was in another playoff for the U.S. Open title at the Chicago Golf Club and this time he won, despite sending his first two tee shots of the playoff out of bounds. John McDermott was youngest ever to raise the U.S. Open trophy.

Hagen was given time off to enter the Canadian Open a few weeks later and he sailed across Lake Ontario to Toronto and finished 11th in his first professional tournament at Rosedale Golf Club. The next year, 1913, saw big changes at the Country Club of Rochester. Donald Ross was brought in to expand the course to a full 18 holes and Andy Christie moved on to a club job in Vermont. Hagen was elevated to club professional but he still needed to summon all his charms to wrangle four days off from the Green Committee to play in the U.S. Open.

Johnny McDermott, the first native-born U.S. Open champion, sits with his trophy from 1912.

Hagen headed to The County Club in Brookline to compete not just against McDermott but the great English pros, Harry Vardon and Ted Ray, who were competing in American national championship for the first time. The Brits were in a particularly pugnacious mood after the brash Philadelphian had destroyed Ray by 14 strokes and Vardon by 13 in a tournament at Shawnee a few weeks earlier.

The unknown club pro from Rochester playing in his second professional tournament haunted the leaderboard until a poor back nine on the final round left Hagen three strokes out of the famous playoff won by Francis Ouimet. McDermott was one stroke further back. Just as Hagen’s golf was getting underway, however, he faced a vexing career decision.

Hagen was good enough at baseball to begin playing semi-pro ball with the Rochester Ramblers at the age of 15, earning $1.50 a game. With an ambidextrous Hagen often on the mound the Ramblers won three consecutive city championships. Baseball was the true national pastime in 2014 and an offer to try out with the Philadelphia Phillies was hard to pass up.

When Ernest Willard, publisher of the Rochester Democrat & Chronicle learned of the offer he counseled Hagen to forget about baseball and offered to sponsor his trip to the U.S. Open in Chicago.Hagen took the golf trip but never lost his love of baseball, almost purchasing the Rochester Red Wings in 1927 before the club was taken over by Branch Rickey and the St. Louis Cardinals.

Hagen opened the tournament at Midlothian Country Club with a 68 the lowest score ever shot in United States Open competition; Ouimet almost matched him with a 69. Hagen led all four rounds but his championship was not assured until hometown favorite Chick Evans’ birdie bid on the 18th hole died on the lip. Ouimet finished tied for fifth, McDermott tied for ninth.

With a 21-year old U.S. Open champion and a 22-year old two-time champion American professional golf seemed primed for a big future. But it was not to be, at least for John McDermott. Later in 1914 he experienced a mental breakdown in a golf shop in Atlantic City. He was committed to the Pennsylvania State Hospital for the Insane with paranoid schizophrenia and spent the better part of his last 55 years in institutional care. He continued to play golf on the hospital's six-hole golf course but the outside golf world mostly forgot about the first American-born U.S. Open champion.

Walter Hagen was left to invent professional golf himself. He stayed on as pro at the Country Club of Rochester until 1918 before moving on to Oakland Hills in Michigan. He represented the club as he won the U.S. Open and at the banquet in his honor he resigned to become the first incarnation of a “touring professional.” Hagen had very strong ideas for what that meant - it would be first class all the way in an era when club pros were considered more like servants. He carried himself not only as if he belonged to a private club but as if he owned it. He was addressed as Sir Walter or The Haig.

Hagen traveled the world playing exhibitions for which he could be paid as much as $1,000. He would do seven, eight, or nine a week on a tour. Walter Hagen would become the first athlete to earn one million dollars and, as his friends would say, the first to spend two million. "I never wanted to be a millionaire,” he said. “I just wanted to live like one."

He also cashed professional golf checks when he could. He won five PGA Championships and five Western Opens among as estimated 75 tournament wins. He also won two United States Opens and four British Opens but there was something unsatisfying about those titles - Bobby Jones was never in the field for any of them.

In the 1920s amateur golf was not a feeder into professional golf. The two traveled in their own universes and the amateur circle, thanks to Jones, enjoyed the greater prestige. In 1926, partly to assuage his ego and partly to score a big payday, Hagen, then 33, engineered a 72-hole challenge match against 23-year old Jones in Sarasota, Florida.

Today such a contest would be an overhyped pay-television sensation. The beloved amateur champion from a patrician background against the flamboyant hard-living professional. The golf courses selected were one favored by Jones - a Donald Ross-designed course now known as Sara Bay Country Club - and Hagen’s choice, the Pasadena Golf Club.

Jones, who spent most of his time preparing for the Georgia bar exam, got off to a slow start during the first day of play at “his” course. At the end of the day Hagen was 8-up and it was reported that, “Walter Hagen had gone around in 69 strokes and Bobby in 69 cigarettes.” After a week’s rest the players returned to the match and Jones did not fare much better before being closed out 12 and 11.

Hagen received a reported $7,800 from the gate receipts. He donated a large chunk to the St. Petersburg Hospital and bought Jones a $1,000 pair of platinum-and-diamond cuff links. For his part an exasperated Jones summed up the experience: ““I would rather play a man who is straight down the fairway with his drive, on the green with his second, and down in two putts for his par. I can play a man like that at his own game, which is par golf. If one of us can get close to the pin with his approach, or hole a good putt, all right. He has earned something that I can understand. But when a man misses his drive, and then misses his second shot, and then wins the hole with a birdie…it gets my goat!”

In 1927 Hagen captained the first American Ryder Cup team in matches between American professionals and British professionals. He had helped arrange an informal such match in 1921 at Gleneagles in Scotland and had participated in another unofficial get-together before the 1926 Open Championship where he and partner Jim Barnes were thumped 9 and 8 by a team of Abe Mitchell and George Duncan in foursomes competition.

Abe Mitchell provided the model for the golfer atop the Ryder Cup.

At tea after the 1926 matches players from both sides, including Hagen, hashed out the format for an official international team competition. Samuel Ryder, who had made his money selling seeds in “penny packets” and had never played golf before the age of 50, agreed to pony up the money for a gold chalis that would be winners’ to hold until the next match. There would be no prize money given to the professionals. Ryder suggested that the likeness on the cup be that of Mitchell, who he had retained as his private swing guru. All agreed. Mitchell and Hagen would captain their respective teams.

Mitchell unfortunately contracted a bout of appendicitis and did not sail to America for the first matches at Worcester Country Club in Massachusetts. Ted Ray, a past Open and U.S. Open champion, took his place; at age 50 the oldest player in the competition. The American team had been thrashed in the previous unofficial team competitions in Great Britain but on American soil with a larger group of pros to choose from Hagen’s team won easily, 9 1/2 to 2 1/2.

Hagen would captain the first six American Ryder Cup teams. The home side won each of the first five matches until the Americans won at Southport and Ainsdale Golf Club in Southport, England in 1937. Hagen, then 44 years old, served as the first-ever non-playing captain in that event. He finished with a 7-1-1 match play record in Ryder Cup competition, including a foursomes match in 1929 when he and Densmore Shute won every hole against Duncan and Arthur Havers.

After a lifetime of globetrotting Hagen bought what he considered his first home on a knoll overlooking the water in Traverse City, Michigan in 1956. He was also happy to surrender the limelight and disappeared from the golfing scene.

Walter Hagen was a favorite of golfing fans and cartoonists during the Roaring Twenties.

When the PGA held a testimonial tribute in Traverse City when Hagen was suffering from throat cancer Arnold Palmer said, “The biggest thrill I got when I set a British Open record of 276 strokes at Troon (1962), was to have Walter Hagen phone me from Traverse City to congratulate me. I didn’t even know The Haig knew I was alive until then. If it were not for you, Walter, this dinner would be downstairs in the pro shop and not in the ballroom." He served as a pallbearer at Hagen’s funeral in 1969.

In 1953 the Country Club of Rochester hosted the U.S. Women’s Open. Betsy Rawls, won the second of her four Open titles. The first had come two years earlier, only six years after taking up the game in Texas at the age of 17. The USGA. In 1959 Robert Trent Jones was brought back to his hometown to update Ross’ course so it was a different test when Susie Maxwell Berning won her third U.S. Women’s Open. Berning, who was the first woman to receive a golf scholarship and compete on the men’s team at Oklahoma State University was something of an Open Specialist as she won only eight other LPGA events.

The Country Club of Rochester course went under the knife one more time in 2004 when it was restored by Gil Hanse, architect for the links-style Olympic Course in western Rio de Janeiro, Brazil when golf returns to the Olympic Games in 2016. And still standing behind the 17th green, watching 120 years of transformation, is the house where Walter Hagen was born and raised.

Van Cortlandt Park Golf Course (1895)

In 1899 as the shades were lowered on the 19th century there were almost 1,000 golf courses in America, a scant dozen years from the time the first players were trying their skill with featheries and hickory-shafted clubs. With rare exception, all of those courses had one thing in common - play was limited to private members.

The first of those exceptions - the first public golf course in the United States - appeared in the Bronx, New York in 1895, although its founders did not set out to open the game to the masses. A group of Manhattan golf enthusiasts calling themselves the Mosholu Golf Club was fruitlessly searching for a tract of private land inside New York City that would be large enough to handle a first-class club with nine full holes of golf. Failing in their quest, the Mosholu men turned to James A. Roosevelt, seventy-year old uncle of Teddy Roosevelt and a member of the Board of Parks Commissioners for help.

Roosevelt saw the recreational value of such a scheme but could not put a municipal asset in private control. A compromise gave the Mosholu golfers a chunk of the more than 1,000 acres of ancestral land the Van Cortlandt family had sold to the city for parkland in 1888. In return the Mosholu Golf Club, led by T. McClure Peters, would build the golf course and lay out the requisite hazards and greens. New York City would pick up the tab ($624.80) but there was one catch - Mosholu would retain exclusive use of the course for only two afternoons a week. The rest of the time the Van Cortlandt Park golf course would be open to the general public.

Tom Bendelow launched his career as the "Johnny Appleseed of American Golf" from the public golf links at Van Cortlandt.

Opening day was July 6, 1895. Golfers found an unusual layout for the 2,561 yard course. None of the first eight holes stretched beyond 200 yards but the ninth was a 700-yard monster that required golfers to play across two stone walls and two serpentine streams. Long holes are still a trademark of Van Cortlandt - the modern configuration boasts two of the longest par fives in the metropolitan New York region, the 625-yard second and the 605-yard 12th. Van Cortlandt was a success from the beginning, not the least because it was free to play. The only charge was if a golfer wanted to hire a caddy. The course quickly became overcrowded which led to poor playing conditions and outbreaks of unruly behavior. New York papers screeched about the golfing degradations at Van Cortlandt.

In December of 1895 a delegation from Boston arrived to investigate this experiment in municipal golf in New York City. On October 26, 1896 to Bostonians converted a slice of Frederick Law Olmsted’s Franklin Park, named for native son Ben, into its own public golf course. Unlike Van Cortlandt, however, Boston puts its municipal golfing fates in the hands of professional golfer Willie Campbell who had once been one of a fabled quartets of “boy wonders” growing up in his native Scotland in the 1880s. At Franklin Park, the 34-year old Campbell was paid three dollars per day which came out of tickets sold for 12.5 cents to play the course.

Within three years Franklin Park was handling over 40,000 loops per year on its nine-hole layout. The New York Times took notice and pegged the troubles at Van Cortlandt to the lack of leadership while praising the Boston public golf model, “Boston has had an excellent one (public golf course) for one or two years in Franklin Park, and its excellence is due largely to the fact that Willie Campbell has charge of the links.”

The New York City Parks Department responded by hiring Thomas Bendelow to manage operations and set aside 65 more acres to expand the facility into the nation’s first 18-hole public course. Bendelow was born into a large family in Aberdeen, Scotland in 1868. Although he took up golf at the age of five and played a proficient game he began his working life as a typesetter for an Aberdeen newspaper. When he sailed to New York City in 1892 it was to join the composition team on the New York Herald.

Bendelow soon became aware of the growing American fascination with golf and the ease of anyone who sounded remotely Scottish to get a job in the game. He hooked up with the country’s leading sporting goods company, A.G. Spalding & Brothers, to promote the development of new golf courses around New York and New Jersey to stimulate the sale of equipment. Bendelow would walk a potential piece of ground driving stakes into the turf where tees and hazards and greens should be constructed. It was a practice used by Old Tom Morris and his ilk back in Scotland as they felt the direction of the winds and the feel of the land.

Bendelow thrived in his role at Van Cortlandt and he quickly established order at the facility, which included a reservation system. The golfing census for 1899 was 2,000 golfers. In 1901 the city opened the Pell Golf Course at Pelham Bay Park which helped relieve some of the congestion in the Bronx. New york City now owns and operates a dozen courses. In 1902 a new golf house was built to service Van Cortlandt and it remains in service, including original wooden lockers, today. The locker room even took a star turn in Oliver Stone’s Wall Street in 1987.

Bendelow’s impressive turnaround of Van Cortlandt inspired Spalding to hire him back, transplanting him to their Chicago headquarters as head of their golf division. In that capacity he traveled to countless small towns in the United States and Canada helping communities establish public golf courses. Known as the “Johnny Appleseed of American Golf,” Bendelow is credited with designing 500, 600, 700 or 800 course, depending on who is doing the counting. These courses were often simple layouts with small, flat greens to better serve the limited coffers of population-challenged municipalities. In the 1920s Bendelow would sign on as the chief designer of American Park Builders and with bigger budgets would design such acclaimed tracks as Medinah Country Club.

Meanwhile “Vannie,” as the locals called it, settled into the mainstream of New York City life. It was not unusual to see Babe Ruth or Willie Mays or Sidney Poitier out on the golf course. Moe Howard, Shemp Howard and Larry Fine - better known as the Three Stooges - called Van Cortlandt their home course. In season 6 of Seinfeld Kramer tees it up at Van Cortlandt.

Bendelow’s design was disrupted by Robert Moses in the 1940s who routed the Major Deegan Expressway through the park. Architect William Follet Mitchell rearranged fairways and built four new holes to replace a couple of lost ones. During the term of Rudy Giuliani more than four million dollars of improvements were initiated that spruced up 20 tee boxes, 13 bunkers, and revitalized the fairways. But the 1 Train from Manhattan still stops right by the 18th green.

Garden City Golf Club (1897)

Walter Travis was the first superstar of American golf. Or perhaps more pointedly, the Leonardo Da Vinci of American golf. He won three of the first four U.S. Amateurs in the 20th century. He was the first American to win the British Amateur. He was a pioneering golf journalist. He was a teacher whose instruction was lauded by Francis Ouimet and Bobby Jones. He was an architect who built the best greens in the world according to Ben Crenshaw. He was a golf equipment innovator. And Garden City was his home course.

Walter J. Travis did not touch a golf club until he was 34 years old and eleven years removed from his native land of Australia. He was 23 years old when his employer McLean Brothers and Rigg sent him to New York City to open a sales office for the firm’s hardware and construction wares. Travis found a wife, became a naturalized American citizen and settled into the New York society whirl. For recreation he hunted and rode bicycles.

Walter Travis always played with a cigar and a flask - he tried to give up smoking and drinking but his game suffered and that was the end of that.

It was with no small amount of disdain that Travis discovered golf in 1896 when his friends in the Niantic Social Club near his home in Flushing announced they were going to form a golf club. Travis had no interest but if his companionable hunting and fishing trips were going to be replaced by afternoons on the links, so be it.

Remembering that fateful first encounter with club and ball, Travis later wrote, “I first knelt at the shrine of the Goddess of Golf.” Within a month of playing his first shots Travis was awarded his first trophy for winning the handicap competition at Oakland Golf Club. As he would add in his memoir, “I shall never ceased to regret the many prior years which were wasted.”

Travis certainly acted quickly to ill his years remaining. He read everything available on golfing technique and adapted it to his self-taught swing that began with a baseball grip and included fat, black Ricoro Corona cigars and a jigger or two of Old Crow whiskey on the course. Most importantly he recognized the paramount importance of the short game. After close defeats in both the 1898 and 1899 U.S. Amateur championships “The Old Man,” as he quickly came to be known, was widely acclaimed as the most deadly putter of the age.

Travis broke through to the top of national tables in 1900 by capturing the U.S. Amateur at his home course in Garden City. The course was laid out in 1897 by Deveraux Emmet as a diversion for guests of the Garden City Hotel that had been started by pioneering department store magnate A.T. Stewart in 1873. Emmet was the quintessential American Gilded Age golfing character, marrying Stewart’s niece in 1889 and spending most summers touring Europe and checking in on the great courses of the British Isles.

Resting next to the 1901 U.S. Amateur trophy is an early rubber-cored ball that Walter Travis used to win the championship.

The Island Golf Links, as the first nine holes were known, was Emmet’s first foray into golf design and there would be some 150 more over the next four decades. Richard Howland Hunt, a graduate of the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris where his father Richard Morris Hunt had been the first American attendee, drew up the plans for the Victorian-style clubhouse. Emmet tacked on another nine holes and Garden City Golf Club was incorporated on May 17, 1899; Walter Travis was a founding member.

As for equipment, Travis was born a century too early. He experimented with drivers from 42 inches long to 52 inches long and installed smaller diameter cups on the practice green at Garden City to hone his putting skills. In 1901 he became the first golfer to win a major championship with the Haskell wound-rubber golf ball in defending his U.S. Amateur title at Atlantic City Country Club, sending the new ball into widespread use.

In 1902, A.F. Knight, the finest player at the Mohawk Golf Club in Schenectady, New York, built himself a putter with a flat head and a shaft inserted in the center. He substituted aluminum for wood about the same time golfing gadfly Devereux Emmet was visiting Mohawk. Emmet returned to Garden City with a prototype and two days later Travis sent Knight an order by telegram. Travis pronounced the “Schenectady Putter” the best he had ever used, proving it by slaying Britain’s finest golfers in their 1904 Amateur. His greenswork was so precise that the Royal & Ancient banned all center-shafted, mallet-head putters in 1910. When the USGA failed to do the same it was the first time the two ruling bodies of golf had parted ways.

The Schenectady Putter caused the first rift between the two ruling bodies of golf - the Royal and Ancient and the United States Golf Association.

As a golf writer Travis produced an instructional book shortly after winning his first U.S. Amateur - less than four years after he picked up his first club. In 1908 he founded one of the earliest and most influential golf magazines, The American Golfer, and remained as editor until 1920. His insights on the game and swing theory were widely respected; Bobby Jones acknowledged that a quick putting lesson from Travis to bring his feet closer together and employ a reverse overlap grip helped transform into a champion-caliber putter.

Travis of course had strong belies about golf course design and he used Garden City as his laboratory during a decade-long stint as Green Committee Chairman. He retained Emmet’s admired routing but filled in the cross bunkers, contoured the greens and added 50 new sand traps. He was especially enamored with deep pot bunkers and after he became ensnarled in a six-foot deep pit he installed by the 18th green which cost him the 1908 U.S. Amateur it became known forever more as the “Travis’s Coffin” - where he dug his own grave.

Garden City was an early favorite of the USGA, hosting four U.S. Amateurs and a U.S. Open in its first fifteen years of existence. The course was the second in the United States to host the Walker Cup. But since Walter Travis has died only the United States Amateur in 1936 has been staged in Garden City. While stepping off the national stage the course has continued to host its Spring Invitational, one of the leading amateur events in the country since 1902. Since 1940 it has been the Travis Invitational.